Gout – easy to misdiagnose

advertisement

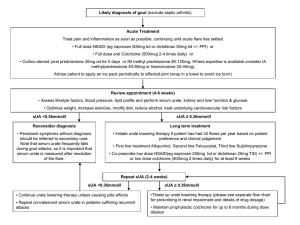

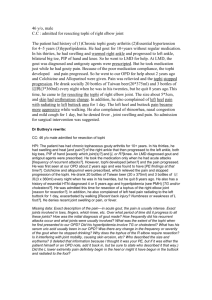

Gout Dr. Pamela Leventis Consultant Rheumatologist Epsom & St. Helier NHS Trust A disease of Kings GOUT – Outline Epidemiology Diagnostic difficulties Management (EULAR/BSR guidelines) Gout – Top tips Epidemiology Commonest Inflammatory Arthritis in men Mean UK prevalence – 1.4% Prevalence increases with age >7% of men >75 yrs, >4% of women >75 yrs (Mikuls et al., 2005) Hyperuricaemia the biggest risk factor for gout Underwood M BMJ 2006;332:1315-1319 Laboratory reference ranges differ between populations – usually 2SDs above/below mean Theoretical Saturation of serum urate – 360μmol/l Pathogenesis Gout is due to extracellular deposition of uric acid crystals in joints Synovial fluid examination under polarised light – negatively birefringent crytals Gout Diagnosis A first hand description The victim goes to bed and sleeps in good health. About 2 o'clock in the morning, he is awakened by a severe pain in the great toe; more rarely in the heel, ankle or instep. This pain is like that of a dislocation, and yet the parts feel as if cold water were poured over them. Then follows chills and shiver and a little fever. The pain which at first moderate becomes more intense. With its intensity the chills and shivers increase. After a time this comes to a full height, accommodating itself to the bones and ligaments of the tarsus and metatarsus. Now it is a violent stretching and tearing of the ligaments-- now it is a gnawing pain and now a pressure and tightening. So exquisite and lively meanwhile is the feeling of the part affected, that it cannot bear the weight of bedclothes nor the jar of a person walking in the room. Thomas Sydenham 1683 Podagra ‘seizing the foot’ >97% specificity for gout in context of supportive clinical presentation and hyperuricaemia (Rigby and Wood, 1994) Why can gout be difficult to diagnose? Atypical Joint/tendon/bursa involvement Pre-existing joint pathology Gout- a great mimic Roddy E, Doherty M. Gout. In: Warburton L (ed). Musculoskeletal disorders in primary care. London: RCGP. In press 2011. Roddy E. (2011) Arthritis Research UK Gout or Septic Arthritis? Gout or Cellulitis? Gout or Rheumatoid arthritis? Diagnostic ambiguity Gout flare can be associated with Normal Serum urate (~10%) ?serum urate lowered during acute phase response (Urano et al., 2002) Gout triggered by drop in serum urate Mild Leucocytosis Low grade fever Normal X-ray Synovial fluid examination 63-78% sensitivity – degree of operator dependence/sample quality (Swan et al., 2002) Crystals may co-exist with sepsis (case series 30 patients – Yu et al. (2003)) Gout Management Goals of Therapy 1. Minimise morbidity of acute flare 2. Prevent future flares, and thereby prevent joint damage and disability Patient Education and Lifestyle changes Pharmacological Prophylaxis if indicated Management Acute Gouty Flare BSR Guidelines (Jordan et al., 2007) 1st line Full dose NSAID continued for 1-2 weeks – unless contraindication If risk of peptic ulcer disease – co-prescribe Proton pump inhibitor Alternatively Colchicine 500μg bd-qds (higher dosing associated with disproportionate toxicity) Intra-articular corticosteroid injection for monoarticular flare Oral prednisolone for severe/polyarticular flare Urate lowering therapies should not be commenced or stopped during acute gout Management Long term Prophylaxis Non – pharmacological Diet (www.ukgoutsociety.org) Alcohol < 21 U/wk ♂, <14 U/wk ♀ Obesity – aim for ideal BMI Exercise Smoking Strong association between gout and the metabolic syndrome (Choi et al., 2007) Annual Screen- BP/Weight/fasting lipid profile/glucose Management Long term Prophylaxis - Pharmacological When to initiate urate lowering therapies? EULAR/BSR Guidelines Uniform agreement for prompt treatment in: Severe gout with X-ray changes Tophaceous deposits Chronic kidney disease Nephrolithiasis Urinary uric acid excretion exceeding 1100 mg/day (6.5 mmol) Otherwise shared decision with patient re: risks/benefits of treatment/no treatment BSR guidelines suggest initiation of treatment if ≥ 1 further attack within 12 months Management Long term Prophylaxis - Pharmacological 1st line urate lowering therapy (BSR/EULAR guidelines) Uricostatics – Xanthine oxidase inhibitor Allopurinol – starting dose 100mg od Jordan et al., (2007) Consider Febuxostat first line in patients with chronic kidney disease Management Long term Prophylaxis - Pharmacological Aim for plasma urate <300μmol/l (BSR guidelines) median [urate] for men in UK <360 μmol/l (EULAR guidelines) saturation point serum urate Commence at least 2 weeks following resolution of acute attack Consider low dose colchicine – 500μg od/bd for up to 6 months following initiation 77% patients flare within 6 months of initiating allopurinol (Borstad et al. 2004) Allopurinol dosing Increase every 2-4 weeks by 100mg until target serum urate achieved. Maximum 900mg/day. Start low – go slow approach recommended To reduce likelihood of triggering attack To minimise risk of toxicity (AHS) Emphasis on target value Allopurinol Hypersensitivity Syndrome 1:300 patients At risk groups: Elderly and Renal Impairment Erythematous desquamating rash Fever Hepatitis Eosinophilia Worsening renal function 20% mortality (Lee et al., 2008) Management Long term Prophylaxis - Pharmacological 2nd line – failure to reach target serum urate If normal renal function uricosuric (Contraindicated if history of nephrolithiasis) Sulphinpyrazone - 200-800mg/day Probenecid – named patient basis Benzbromarone if mild – moderate renal impairment (GFR 3060ml/min) – named patient basis Or combination therapy Losartan and Fenofibrate – weak uricosurics Management Long term Prophylaxis - Pharmacological Febuxostat currently approved by NICE if: adverse effects on allopurinol OR further dose escalation contra-indicated with suboptimal serum urate most common side effects diarrhoea, nausea, headache, abnormal LFTs, rash Renal Uric acid Excretion Urinary uric acid:creatinine ratio to diagnose over excretors Should be determined in : Young patients diagnosed with gout <25 yrs Patients with a family history of young onset gout Patients with renal calculi BSR gout treatment algorithm Jordan et al., 2007 Future Treatments Uricases – convert urate to allantoin ?debulking urate load in tophaceous gout IL-1 antagonists to treat severe acute flares Anakinra, Canakinumab Gout – Top Tips 1. Gout is very rare in pre-menopausal women, 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. referral advised. Hyperuricaemia + joint inflammation ≠ gout Serum urate is often normal during a gouty flare. X-rays are not useful in acute/early gout. Avoid any changes to Allopurinol dosing during or within a fortnight of an acute flare of gout. Commonest cause for Allopurinol failure is non compliance. REFERENCES Mikuls TR, Farrar JT, Bilker WB et al. Gout epidemiology: results from the UK general practice research database, 1990-1999. Ann Rheum Dis (2005), 64:267-272. Underwood M. Diagnosis and management of gout. BMJ. 2006; 332: 1315-1319 Lee H Y, Ariyasinghe J T N, Thirumoorthy T. Allopurinol hypersensitivity syndrome: a preventable severe cutaneous adverse reaction? Singapore Med J 2008; 49(5) : 384 Borstad GC, Bryant LR, Abel MP et al. Colchicine for prophylaxis of acute flares when initiating allopurinol for chronic gouty arthritis. J Rheumatol (2004), 31:24292432 Zhang W, Doherty M, Pascual E et al. EULAR evidence based recommendations for gout. Parts I and II. Ann Rheum Dis (2006), 65:1301-1324 Jordan KM, Cameron JS, Snaith M et al. British Society for Rheumatology and British Health Professionals in Rheumatology guideline for the management of gout. Rheumatology (2007), 46:1372-1374 http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/TA164Guidance.pdf Febuxostat for the management of hyperuricaemia in people with gout