Collective Decision-making in Sovereign Debt

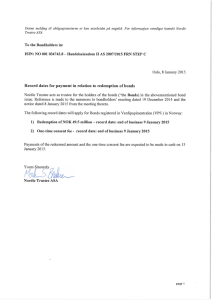

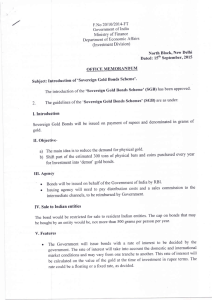

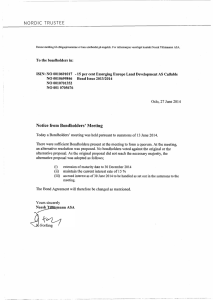

advertisement