HA-18-7-13

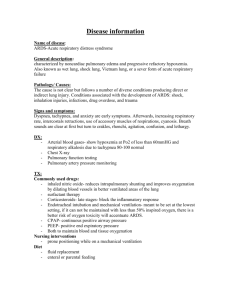

advertisement