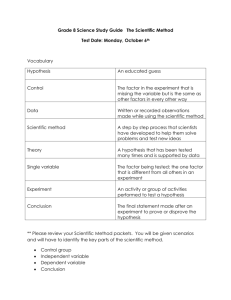

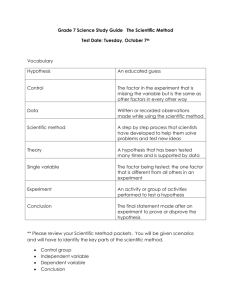

Writing a Lab Report

advertisement

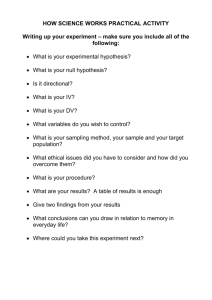

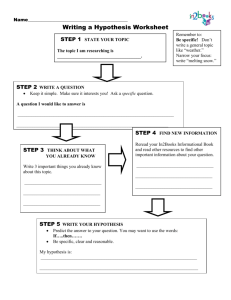

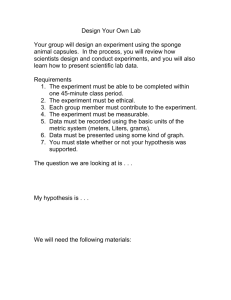

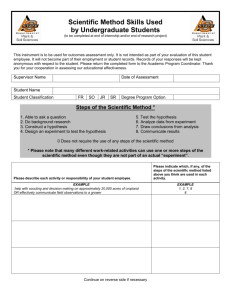

Writing a Lab Report You will be writing formal lab reports for lab exercises that are investigative. This means that these are labs where you are trying to answer a specific question. They will generally be labs where you design the procedure you will use. Sometimes the question will be posed for you and sometimes you will pose your own questions. These are labs where your lab group’s lab exercise will be unique. It is important for you to record what you did and what happened accurately. The format for your lab report is outlined on the next page. Once you have completed your lab report, use the checklist below to make sure your report is complete and correctly formatted: Introduction (in a well-developed paragraph) Clearly states the question you are trying to answer Gives enough background for the reader to understand the basis of the question States your hypothesis about the answer to your question Explains your reasoning for your hypothesis Makes a specific prediction about the results you will expect if your hypothesis is correct Procedure (must be in well developed paragraphs) Experimental design is a controlled experiment (Tell what your control is and tell what variables are standardized. Gives enough detail so the reader could duplicate your experiment Cites references to previously used procedures where appropriate Uses appropriate style (i.e. uses past tense, avoids words such as I and we, uses complete sentences, in paragraph form, etc.) Tell what your control is and how many times you replicated your experiment. Results (may be in the form of a graph, a table, a picture, or a narrative) Summarizes the data (attach raw data at the end of your report, but do not include it in your formal report.) Presents the data in the most effective format (table, graph, etc.) Presents tables and figures neatly so they are easily read Labels the axes of each graph completely Gives units on all measurement Includes a descriptive title for each graph, table, and figure Includes an explanation of any calculations you did to arrive at the data you are presenting Conclusion (in well-developed paragraphs) Restates purpose of the lab Restates your hypothesis and makes a prediction in “if…then” form States whether or not results support your hypothesis Cites specific results that support your conclusions Explains the reasoning for your conclusion Discusses your conclusion in context of previous knowledge Discusses any weaknesses in your experimental design, problems with execution of the experiment, and sources of error Suggests how sources of error may have affected results Clearly summarizes your conclusion in a sentence or two at the end Uses complete sentences and proper writing practices throughout Lab Group Class Date Name of Experiment Introduction: This section should begin by explaining the reason for doing the experiment. Tell what you are trying to learn in a clear, concise, and easily understood sentence. Then explain any background material that your reader will need to understand the importance of your question, your chosen procedure, and your reasons for making your hypothesis. Now you can state your hypothesis and explain your reasoning. Why are guessing this particular answer for the question you posed? Finally, make a prediction about the specific results you will expect if your hypothesis is true. This sentence will probably begin with the words “If my hypothesis is true, then …”. The introduction will usually be a single paragraph or two. Procedure: In this section you will give a detailed account of your experimental procedure. In order to be considered valid, the results of a scientific investigation must be able to be duplicated by other scientists. It is therefore necessary for you to provide complete details on how you completed your investigation. If you are using a technique from a lab we have previously done in class you do not need to include the details of the procedure in you lab report. You may simply cite the lab where the procedure is detailed. Example: Samples were tested for the presence of starch using the iodine test. (See Lab #3, Comparing Sugars and Starches) This section should be done in paragraph form with complete sentences throughout. Use past tense, but avoid words such as “I, Her, We, She,” etc. This means you will be using passive voice. (“The mixture was heated over a Bunsen burner for 3 minutes.”) Keep in mind that you should not usually use passive voice in other writing. Some scientists are changing the format for scientific writing and write in the active voice with the use of “I” or “We”. However, many scientific journals still insist on the passive voice format, so you should use it for your lab reports (but NOT in your English papers!). Remember that multiple trials are part of good experimental design, so tell how many trials you performed. (If you only performed a single trial due to time constraints, say so.) Results: In this section you will present your data in an organized, readable form. You should use tables to present numerical data. Use graphs to present relationships between factors. Each table and graph must include a descriptive title. Data may also include diagrams, sketches, and written observations. It is important for you to consider the most effective way to present your data. If the purpose of your lab is to determine a relationship between two quantities, then a graph is probably the most effective presentation. Remember the rules for deciding between using a line graph and a bar graph. ONLY AVERAGES FROM MULTIPLE TRIALS SHOULD BE INCLUDED IN YOUR FORMAL REPORT! Raw data (the actual numbers you wrote down) should be attached at the end of your report. This should NOT be recopied or typed! It is not part of your formal report and is only included to verify the accuracy of your presented data. (Scientists would keep this original of their data in their lab notebooks.) You should also include an explanation of any calculations that you made from your raw data. (For example, did you average the results from two trials?) Keep the following points in mind when preparing graphs: Graphs should be done in Excel and pasted into the appropriate section of your report. Label the axes completely (including units). Use the entire area of the graph to display your data. Choose appropriate intervals and mark them evenly along the axes. Each graph must have a descriptive title. Conclusion: In this section you should interpret the results, explain their significance, and discuss any weaknesses of the experimental methods or designs in well-developed paragraphs. This is the most important section of your lab report. It is also the most difficult to write. Make sure you have completed all other parts of the lab report before you attempt to write the conclusion. Also make sure you have presented your results in the best form. Raw data is usually difficult to interpret. With your results in front of you, use the following steps to help you write your conclusion: Restate the purpose of the lab. State this clearly in a complete sentence. Restate your hypothesis and recall the prediction you had made for your results based on your hypothesis (use “if…then” form). This generally requires at least two separate sentences, one for your hypothesis and a second for your prediction. (You do not need to repeat your explanations of the reasons for the hypothesis here.) Decide whether your results supported or refuted your hypothesis or were inconclusive. To do this compare the predictions you made with your actual results. Give specific examples of data that either supports or refutes your hypothesis. REMEMBER THAT DATA MAY SUPPORT YOUR HYPOTHESIS, BUT NO SINGLE EXPERIMENT CAN PROVE YOUR HYPOTHESIS. Avoid the word prove throughout your conclusion! Explain how your results fit in with what you already know from your class work or prior experience. Speculate on possible reasons for any unexpected results. List sources of error in your experiment. Be specific. Make sure to include any problems that arose as you conducted your experiment and tell how they may have affected your results. Recommend changes that you would suggest for someone attempting to duplicate your research. Remember that there is always some uncertainty inherent in every measuring device you use. It is virtually impossible to perform an experiment without some source of error. In a single sentence or two summarize what your results mean in terms of the answer to the original question posed in your purpose. Lab reports will be graded according to the following rubric: Introduction (5 points possible) Clearly states all required points in a well written paragraph 5 points Required points included in a paragraph, but some points unclear or incomplete 4 points Required points included, but not in paragraph form 3 points Some required points missing Procedure (4 points possible) Results (5 points possible) Introduction missing 0 points Good design and details, with proper references and style 4 points Good design, but minor problems with details, references, or style 3 points Minor problems with design or major problems with details, references or style 2 points Major problems with design 1 points Procedure missing 0 points Presents results in best format, completely labeled and neat 5 points Good presentation, but minor omissions, errors, or messiness 4 points Poor format for data presentation or major omissions, errors, or messiness 3 points Major problems with data presentation Conclusion (6 points possible) 1-2 points 1-2 points Results missing 0 points Includes all required steps, in well written paragraphs that are clear, concise, and in line with results 6 points Conclusion answers question posed, but is not fully explained or supported, makes a few incorrect statements, or contains minor omissions in required steps Conclusion is unclear or incomplete, does not answer question posed in purpose, makes many incorrect statements, is not written in complete sentences, or contains major omissions in required steps 4-5 points 2-3 points Conclusion not at all in line with results 1 points Conclusion missing 0 points Sample Lab Report Students’ names October 14, 2009 Lab #6: The Effect of Light on Plant Growth Introduction: The purpose of this experiment is to determine how the number of hours spent in the light each day affects the growth of bean seedlings as measured by the seedlings’ height. Plants obtain the energy they need for growth from the process of photosynthesis. Light is necessary for photosynthesis, so it is to be expected that plants spending more hours in the light would have more energy available. For this reason, it is our hypothesis that plants receiving more light each day will grow taller. If our hypothesis is correct, then the plants receiving eight hours of light each day will be taller than the plants receiving lower amounts of light each day. Procedure: Twenty-five bean seeds were planted 2 cm deep in each of five identical flats containing 10 cm of Peter’s Professional potting soil. (Seeds were spaced evenly in rows 3 cm apart.) One flat was placed in a plant cart where the lights were always off. A second flat was placed in a plant cart where the lights were turned on for 2 hours each day. A third flat was placed in a plant cart where the lights were turned on for 4 hours each day. A fourth flat was placed in a plant cart where the lights were turned on for 6 hours each day. A fifth flat was placed in a plant cart where the lights were turned on for 8 hours each day. All plant carts were maintained at 25 ˚C throughout the experiment. Each flat received 100 ml. of water every 5 days. The height of each bean seedling was measured after 24 days. Height was determined as the distance from the soil to the highest point of the seedling. The plants receiving no light served as the control for the experiment. The experiment was not replicated due to time constraints Results: Average Net Growth in Plants Receiving Various Hours of Light per Day 25 Average Net Growth (cm) 20 15 10 5 0 0 1 2 3 4 5 Daily Light Received (hours) 6 7 8 9 All net growth values are the average change in the height of the twenty-five plants in the flat. Averages were obtained by adding the final heights of each of the plants in the flat and dividing by twenty-five (since all plants had a height of zero centimeters on the first day. It was also noted that plants in the groups receiving little or no light, had stems with a smaller diameter, smaller leaves, a smaller number of leaves, and a more yellow color than plants receiving more light. (Raw data may be found at the end of the report.) (You may paste photos in here if you have them) Conclusion: The purpose of this lab was to determine how varying the exposure to light would affect the growth of bean seedlings as measured by the seedlings’ height. It was our hypothesis that seedlings exposed to light for longer periods of time would grow to greater heights. If this hypothesis were true then we would predict that plants grown with more light would consistently show a greater average height than plants with less light. The results of our experiment did not support our hypothesis. Once the seedlings germinated at around day 6, plants receiving more light had a lower average height on each day of the study. This trend continued throughout the experiment. For example, on day 24 plants receiving 8 hours of light daily had an average height of only 12.2 cm compared to a height of 12.6 cm for plants receiving 6 hours of light daily. Average height on day 24 continued to increase as hours of light decreased with average heights of 14.4 cm for plants grown with 4 hours of light daily, 15.8 cm for plants grown with 2 hours of light daily, and 21 cm for plants grown in the absence of light. It was noted, however, that plants grown with greater amounts of light had thicker stems and larger, healthier looking leaves. Results were similar for each day after day 6. The only time for which hours of light seemed to have little of no effect on plant growth was the period before the seeds germinated. Germination began on or around day 6 for all trials. The results for the first six days make sense in terms of what we have learned about plant growth. Bean seeds are provided with a source of sugar from the starch in the cotyledons, so they do not require additional energy from photosynthesis in order to germinate. Furthermore, since all of the seeds were covered with soil until they germinated, none of the seeds were really receiving much light until after germination. Thus, we saw little difference in the time of germination regardless of time spent in the light. However, the results from the sixth day on were surprising to us. After germination, the sugar stored in the cotyledons was quickly used up. From this point on, we expected growth to depend on sugar provided from photosynthesis. Thus, we expected plants that received more light, and therefore had more sugar available through photosynthesis, to grow to a much greater height. Our results showed the exact opposite relationship between hours of light and growth rate. One possible explanation is that plants may be able to stimulate growth in response to lack of light as a sort of “light-seeking” mechanism. More research is needed to explore this possibility. We also felt that it was significant that the plants grown with more light were sturdier and healthier in appearance. We suggest that another experiment be conducted to collect quantitative data to support this observation. One problem we encountered in performing this experiment was the need to expose all the plants to light during the time the measurements were being made. This was unavoidable since we needed to see in order to make the measurements. This small exposure to light may have influenced our results slightly. Perhaps their growth would have been less if we hadn’t measured them in the light. Future researchers might consider using night vision goggles to make height measurements in the dark. Uncertainty in measuring the lengths may have caused some error, but these should have been similar throughout the experiment and therefore should not have had a significant effect. Our results indicate that, once they germinate, plants exposed to greater amounts of light grow to a smaller average height. Plants grown with no light at all grew to the greatest average height.