Towards a Universalistic Model of Reputational Leadership

advertisement

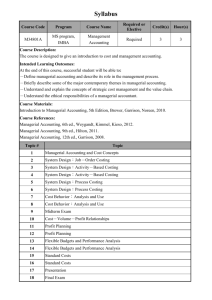

Towards a Universal Taxonomy of Perceived Managerial and Leadership Effectiveness: A multiple cross-case/cross-nation study of effective and ineffective managerial behaviour Refereed Paper Hamlin, Robert G.; Patel, Taran; Ruiz, Carlos: Whitford, Sandi. Abstract Empirical findings obtained from fifteen emic replication studies of peoples’ perceptions of effective and ineffective managerial behaviour within various organizations in Canada, China, Egypt, Germany, Mexico, Romania and the United Kingdom were subjected to a process of derived etic multiple cross-case and crossnation comparative analysis. High degrees of sameness and similarity were found. Further analysis led to the emergence of a ‘universalistic’ taxonomy of perceived managerial and leadership effectiveness comprised of eight positive (effective) and six negative (least effective/ineffective) generic behavioural criteria. The study demonstrates empirically that in all seven countries managerial and leadership effectiveness is perceived, judged, and defined in much the same way and in similar terms. Our findings challenge past literature which argues that managers/leaders need to adopt different managerial behaviours to be effective in different organizational sectors and in different countries. They also challenge the axiomatic belief amongst most management researchers that effective management and leadership processes must reflect the national/societal cultures in which they are found. Limitations of the study and implications for future HRD research and practice are discussed. Keywords: Perceived managerial and leadership effectiveness, universalistic taxonomy, cross-nation research. Most managerial work and behaviour studies from the 1950s through to the present day have been focused on the duration and frequency of activities and behaviours, as opposed to exploring how behaviours are related to measures of effectiveness and what behaviourally distinguishes good managers from poor/bad managers (see Hales, 1986; Fernandez, 2005; Martinko & Gardner, 1985; Shipper & White 1999; Stewart, 1989). And during this same period most leader behaviour studies have been surveybased using questionnaires comprised of pre-determined behavioural dimensions which, more often than not, have measured attitudes about behaviour rather than actual observed behaviour and their effectiveness (Conger, 1998). Furthermore, little effort has been made to confirm the results of such evaluation studies with alternative approaches to survey methods (Den Hartog, Van Muijen & Koopman , 1997). As Avolio, Bass and Jung (1999) argued, the challenge remains as to how exemplary leadership can best be measured beyond simply using survey tools. Thus, despite the volumes of empirical research on leadership, there is still a lack of agreement about which leader behaviours are most relevant and meaningful for leaders (Yukl, Gordon & Taber, 2002); and there is little clarity as to what constitutes ‘managerial effectiveness’ or ‘leadership effectiveness’. 1 We conclude the core question that still needs to be addressed is- What do people within and across organizations, organizational sectors and countries perceive as effective and as ineffective managerial behaviour?- and for two compelling reasons. First is the effect of globalization that has led to an increasing frequency in the transnational employment of managers, an increasing requirement for indigenous managers to work with people from other nations, and an increasing need for expatriate managers to know and understand how effective and ineffective managerial behaviours are perceived within and across different countries (Brodbeck, Frese, Akerblom, et al, 2000; Zhu, 2007). Our second reason is the widely held belief that managers/leaders in public sector organizations should adopt different managerial behaviours to those in private sector companies because of the inherent differences between the two sectors (Baldwin, 1987; Fottler, 1981). But, as Hooijboorg and Choi (1998) pointed out, while many researchers have examined these differences, few have focused on whether management or leadership styles vary, or should vary across sectors. In the absence of hard evidence of managerial and leadership differences and similarities between the sectors, plus a continuing lack of clear unequivocal empirically derived behavioural dimensions of managerial performance/effectiveness criteria, managers/leaders in all sectors will likely operate and behave on the basis of their own individual personal preferences. Thus, building on Flanagan and Spurgeon’s (1996) argument, we suggest domestic and international/global organizations ought to find out the extent to which perceived behavioural determinants of perceived managerial and leadership effectiveness within given organizational sectors and countries are the same or different. Conceptual Background In this section we discuss extant research on ‘managerial effectiveness’ and ‘leadership effectiveness’, the theoretical concepts that have guided our study, its purpose, and also the specific research questions that we have addressed. Past managerial effectiveness and leadership effectiveness research Various past researchers have developed behavioural models or taxonomies of ‘managerial effectiveness’ and ‘leadership effectiveness’ (see Borman & Brush, 1993; Fleishman, et al, 1991; Luthans & Lockwood, 1984; Morse & Wagner, 1978; Yukl & Van Fleet, 1992; Yukl, Gordon & Taber, 2002). However, all of these cited models and taxonomies have been based overwhelmingly on empirical data obtained from studies carried out in North America. Furthermore, there is considerable variability in their content, complexity and comprehensiveness, and many of them are simply retranslations and/or re-combinations of previously published taxonomies (Anderson, Krajewski, Goffin & Jackson, 2008; Tett et al, 2000). Due to the positivist bias in most management and leadership research which has largely favoured quantitative inquiries using quantitative pre-determined survey-based questionnaires, since the early 1980s few researchers have conducted qualitative studies of peoples’ perceptions of effective and/or ineffective managerial and leadership behaviour ‘within’ organizations, or ‘across’ organizational sectors or countries. One ‘within’ organization qualitative inquiry that does stand out in the literature is that of Cammock et al (1995) who explored managerial effectiveness in a large New Zealand public sector organization. Other ‘within’ organization qualitative explorations include the emic replication studies of perceived managerial and 2 leadership effectiveness that were variously carried out by us in the UK and various other countries, either individually or jointly or collaboratively with different coresearchers, plus the equivalent study by Wang (2011). Except for Hamlin’s (2004) multiple-cross-case comparative analysis of findings from his three earliest emic studies of managerial and leadership effectiveness within UK public sector organizations, we have found no equivalent or comparable derived etic study in this area of management/leadership research Theoretical context The ‘theories’ that have guided our study- which also informed explicitly or implicitly the past emic studies upon which our work has been based- include the multiple constituency model of organizational effectiveness and the concept of reputational effectiveness respectively. In using the multiple constituency (MC) approach managers and leaders are perceived as operating within a social structure consisting of multiple constituencies or stakeholders (e.g. superiors, peers, subordinates), each of whom has his/her own expectations of and reactions to them (Tsui, 1990). How managers are perceived and judged by their superiors, peers, and subordinates can be important for managerial success (or failure) because it determines their reputational effectiveness (Tsui, 1984). Furthermore, the type of managerial behaviour that a manager exhibits has reputational consequences (Tsui & Ashford, 1994); for example, his/her behaviour can cause peers, superiors and other key people either to give or withhold important resources such as information and cooperation, or can lead to subordinates either following or not following their leadership. Purpose of the study and research questions Our study builds upon and extends Hamlin’s (2004) work by searching for evidence of universalistic behavioural criteria of perceived managerial and leadership effectiveness that are relevant across organizational sectors and national boundaries. Specifically, we have conducted a qualitative multiple cross-case comparative analysis of findings obtained from the 14 aforementioned past emic replication studies conducted by us and our respective co-researchers, and from Wang’s (2011) study It should be noted that the three earliest of our studies were used by Hamlin (2004) for his UK based study. We addressed the following research questions: (i) To what extent are people’s perceptions of the behavioural determinants (definitions) of ‘perceived managerial and leadership effectiveness’ across a sample of organizations, organizational sectors and nations the same or different? (ii) Where such definitions are found to be held in common (if any), can they be expressed in the form of a universalistic taxonomy? Research Methodology This section provides details of the empirical source data used for our study, how that data was analyzed and interpreted, and how we assured the trustworthiness of our 3 findings. We embraced Tsang and Kwan’s (1999) notion of empirical generalization replication, and adopted Berry’s (1989) derived etic approach to applied research which involves both ‘replication logic’ and ‘multiple cross-case analysis’ (Eisenhardt, 1989). Sampling The empirical source data used for our derived etic study were obtained from the 14 aforementioned emic studies that we have severally conducted within Canada, Egypt, Germany, Mexico, Romania and the United Kingdom respectively, plus Wang’s (2011) equivalent replication study in China, as cited in Table 1. Table 1. Empirical source data used for the present derived etic study The fifteen emic studies of managerial and leadership effectiveness Public Sector Organizations Case UKA-state secondary schools in England Hamlin (1988) Case UKB- a department of the British Civil Service Hamlin, Reidy & Stewart (1998) Case UK C - an ‘acute’ British NHS Trust hospital Hamlin (2002) Case UKD- a ‘specialist’ British NHS Trust hospital Hamlin & Cooper (2007) Case UKE-a local government social services department Hamlin & Serventi (2008) Case EGPT-a public sector hospital in Egypt. Hamlin, Nassar & Wahba (2010) Case MXCO-a public sector hospital in Yucatan, Mexico Hamlin, Ruiz & Wang (2011) Case ROMA- a public hospital in Romania Hamlin, Patel & Iurac (2010) Case CHNA-a public owned company in China Wang (2011) Case CNDA- a public sector electric utility in Canada Whitford (2010) Subject focus of the study* No. of CIT informants No. of CIs collecte d No. of effective BSs No. of ineffectiv e BSs Total number of BSs M 35 340 65 61 126 S, M & FL 130 1,200 43 40 83 S, M. & FL 57 405 30 37 67 S, M & FL 60 467 25 24 49 M & FL 40 218 34 25 59 T, S, M & FL 55 450 25 23 48 M, FL 27 233 18 18 36 T, S, M & FL 35 313 30 27 57 T, S, M & FL 35 230 14 17 31 S, M & FL 57 529 14 18 32 4 Private Sector Organizations 555 31 35 66 Case UKF- a British global S, M, & 55 communications company FL Hamlin & Bassi (2008) 37 370 16 13 29 Case UKG- a British T only international telecoms plc Hamlin & Sawyer (2007) 154 15 19 34 Case GER- a T, S, M & 64 heterogeneous mix of FL private companies in Germany Patel, Hamlin & Heidegen (2009) Third Sector Organizations 40 450 42 34 76 Case UKH- a UK S only registered charity in social care and housing for the elderly Hamlin, Sawyer & Sage (2011) 262 34 31 65 Case UKI- independent T, S, M & 33 (private) secondary FL schools in England. Hamlin & Barnett (2011) 760 6176 436 422 858 Totals * Subject Focus: T-Top managers. S-Senior manager. M-Middle managers. FL-First line managers Fourteen of the 15 studies were replications or part replications of Hamlin’s (1988) original managerial behaviour study in UK state secondary schools. In all 15 studies the researchers used Flanagan’s (1954) critical incident technique (CIT) to collect concrete examples (critical incidents-CIs) of effective and ineffective managerial behaviour from purposive samples of participating managerial and non-managerial employees. They then grouped the collected CIs into clusters according to their similarity in meaning to each other. Behavioural statements (BSs) were devised to reflect the constituent CIs (n=3 to 12) in each cluster. As can be seen in Table 1, the number of CIT informants interviewed in each study ranged from 27 to 130; the number of CIs collected by the respective researchers ranged from 154 to 1,200; and the number of discrete BSs derived from the content analyzed CIs ranged from 29 to 120. In total, 436 positive (effective) and 422 negative (least effective/ ineffective) BSs emerged from the 6,176 CIs collected by the respective past researchers from 760 CIT informants. Data analysis The research questions were addressed initially by Author 1 (Robert G. Hamlin) who carried out a deductive and inductive comparative analysis of the BS data sets obtained from all 15 cases. This analysis was conducted at a semantic level (Braun & Clarke, 2006) using open coding initially to disentangle and code the BSs, and then axial coding to identify those that were the same, similar, or congruent in meaning (Flick, 2002, Miles & Huberman, 1994). Sameness was deemed to exist when the sentences or phrases used to describe two or more BSs were identical or near identical. Similarity was deemed to exist when the BS sentences and/or phrases were different, but the kind of meaning was the same. Congruence existed where 5 there was an element of sameness or similarity in the meaning of certain phrases and/or key words. Author 1 then classified and grouped the previously coded BSs using a form of selective coding and thematic analysis (Flick, 2002). The aim was to identify and develop (if possible) a set of core behavioural categories that were underpinned by at least one BS from all 15 cases. The deduced categories were subsequently interpreted and tentatively labelled by Author 1 according to the meaning held in common with all of the respective constituent behavioural statements. Independent of each other, and using Author 1’s descriptive labels as coding categories, Author 2 (Taran Patel), Author 3 (Carlos E. Ruiz) and Author 4 (Sandi Whitford) then deductively coded and sorted the BSs from each of the 15 emic studies. This was followed by Author 1 engaging with all three of them individually in a vice-versa process of mutual code cross-checking (Gibbs, 2007) of each others independent analyses. Where divergences of interpretation and judgment occurred these were reconciled as far as possible through critical examination and discussion to arrive at a consensus. The four authors then worked jointly to identify commonalities and relative generalizations across their four independent analyses in order to deduce behavioural categories comprised only of BSs where there was common agreement between them. The so derived and interpreted behavioural categories, which we call generic behavioural criteria, were given descriptive labels that reflected in essence the meaning of the BSs constituting each criterion respectively, and used as the basis for deducing a universalistic taxonomy of perceived managerial and leadership effectiveness. Trustworthiness of the findings Credibility and dependability were achieved through the processes of ‘realist triangulation’ (Madill, Jordon & Shirley, 2000) and ‘investigator triangulation’ (Easterby-Smith, Thorpe & Lowe, 1991). This involved using multiple sources of empirical data (namely the BSs obtained from the 15 emic studies carried out in 7 countries) that had been generated by the multiple researchers who had conducted them. The empirical source data were suitable for comparison because the same research design and common CIT protocols for data collection and analysis had been used for all of the emic studies. This assured consistency in the research focus and processes. The cumulative confirmation of the convergence and consistency of meaning of the obtained empirical source data, which was achieved through realist qualitative comparative analysis/triangulation whereby the four of us first worked independently and then jointly to arrive at a consensus judgement, assured the accuracy and objectivity of our derived etic study (Knafl & Breitmayer, 1991). Results The result of our multiple cross-case and cross-nation comparative study has demonstrated empirically that people operating within different types of organizations, organizational sectors and national contexts perceive the behavioural determinants of effective and ineffective managerial performance in much the same way. The main contribution of our work is the emergence of 8 positive (effective) and 8 negative (ineffective) generic behavioural criteria of ‘perceived managerial and leadership effectiveness’ as listed in Table 2. 6 Table 2 Generic behavioural criteria of ‘perceived managerial and leadership effectiveness’ Positive (Effective) Behavioural Criteria 1. Good planning and organizing, and proactive execution, monitoring and control Negative (Ineffective) Behavioural Criteria 1) Poor planning, organizing and controlling, bad judgment ,low standards and/or tolerance of poor performance from others 2) Shows lack of interest in or respect for staff, and/or care or concern for their welfare or well-being 2. Supportive management and leadership 3. Delegation and empowerment 4. Shows care and concern for staff and other people 5. Actively addresses and attends to the learning and development needs of their staff 6. Open, personal and trusting management approach 7. Involves and includes staff in planning, decision making and problem solving 8 Communicates regularly and well with staff, and keeps them informed 3. Inappropriate autocratic, dictatorial, authoritarian and non-consultative, non-listening managerial approach 4. Unfair, inconsiderate, inconsistent, and/or selfish, manipulative, self-serving behaviour 5. Active intimidating, and/or undermining behaviour 6. Slack management, procrastination in decision making, ignoring problems and/or avoiding or abdicating from responsibilities 7 Depriving and/or withholding behaviour 8. Exhibits parochial behaviour, a closed mind, and/or a negative approach Our study suggests that regardless of the organizational, sectoral, or national context managers are likely to be perceived effective by their superiors, peers and subordinates when they:- are good in planning and organizing and proactive in execution, monitoring and control; manage and lead in an active supportive manner which includes promoting and fighting in the interests of their staff and department/unit; when they:- delegate well and actively empower their staff; show care and concern for staff if faced with personal difficulties; and also when they:- are generally open, approachable, personal and trusting in their managerial dealings with people. Additionally, managers are perceived effective when they:- actively attend to the learning and development needs of their staff; involve and include them in planning, decision making and problem solving; and when they communicate regularly and well with their staff and keep them informed on organizational matters that will affect them. Conversely, managers are likely to be perceived least effective or ineffective not just when they fail to exhibit positive (effective) managerial behaviours, but also when they are perceived to be unfair, inconsiderate, selfish, manipulative, self-serving, undermining and/or intimidating; or when they are inappropriately autocratic and non-consultative, and/or exhibit behaviours indicative of slackness or procrastination in the way they manage; or when they ignore and avoid and/or abdicate from their managerial responsibilities. Additionally, managers are perceived least effective/ineffective when they actively or negligently deprive and/or withhold from staff such things as key information, clear instructions, 7 guidance, adequate resources, recognition, praise or feedback, and when they exhibit parochial behaviour, a closed mind or a negative approach. To illustrate the convergence of meaning of the behavioural statements from the 15 cases that underpin the 16 identified generic behavioural criteria, the full behavioural content of the negative behavioural criterion Unfair, inconsiderate, inconsistent and/or selfish, manipulative, self-serving behaviour is given in Table 3. Table 3 Illustration of the convergence of meaning of the behavioural statements underpinning one behavioural criterion Unfair, inconsiderate, inconsistent and/or selfish, manipulative, self-serving behaviour Public Sector Cases UKA Loads self with easy/quick to mark exam papers while allocating to staff those that are time consuming; Timetables examinations and report writing in same week without giving consideration to the effects on staff with already heavy workloads; Refuses to change own plans or working arrangements in order to help or make things easier for a colleague HoD; Allocates a disproportionate number of the academically bright pupils and/or VIth Form classes to self to teach; When arranging outside events omits to announce the arrangements to colleagues until the day of the event and then expects pupils to be released from lessons at very short notice; Takes all the credit for departmental achievements and omits to thank or praise the efforts of the staff; Accepts teaching timetables for the department which, from the point of view of the staff, are not conducive or wholly practical for effective teaching by virtue , for example, of classes being too large and/or the walking distances between classrooms too great for carrying heavy equipment; If involved in selecting replacement staff, avoids choosing the strongest candidates with forceful personalities and qualities of leadership, in preference for weaker candidates who can be easily handled/manipulated; Nominates self or deputy to attend external ‘in-service’ training courses and not the staff; Opts out if he cannot easily get his own way(with peers) at meetings of Department Heads; Allows own personal preferences and prejudices to influence/bias the way he represents the views and opinions of his staff to higher management; Refuses to broaden the curriculum to help develop skills linking in with other subjects for fear of devaluing the subject specialism. UKB Excuses himself from blame and/or blames others when things go wrong; Shows favouritism when allocating resources such as office accommodation, furniture, IT equipment.; Within the promotional system exhibits favouritism; Takes all the credit for success achieved by own team members; Adopts an uncooperative attitude towards others (e.g empire building at expense of other units; refuses to work with peers/teams from the Headquarters); Adopts a narrow, parochial and/or selfish attitude; Delegates to staff own managerial responsibilities overloading them to the point of personal abdication and subsequently blaming them when things go wrong; Moves own poor performers or problematic team members to other teams thereby leaving the recipient managers to resolve the problems associated with the people; Manifests manipulative or politicking behaviour, saying or doing one things and then changing behind people’s backs; Allows team to run with insufficient or inadequate resources. UKC Is inconsistent and/or unfair in his/her dealings or handling of people; Refuses to admit to their own mistakes or errors in judgment and instead blames others; Exhibits manipulative, politicking and undermining behaviour (e.g. saying one thing but doing another; using delaying tactics; playing one person/group off against another) UKD Does not treat staff equally (e.g. unfairly praises staff when not deserved); Asks a member of staff to stay late to complete a task to meet a deadline but is not prepared to stay over and help; Disregards policy (e.g. makes decisions to meet own needs) Gives [staff] insufficient time to complete jobs (e.g. sits on [allocating] a job until it is critical and then demands the job to be completed in a rush); Refuses to admit mistakes or failings. UKE Blames others for own poor work performance; Shows favoritism; Undermines and manipulates others; Ineffective or inconsistent poor communication across teams. 8 EGYT Treats staff unequally, unfairly and preferentially. Exhibits selfish and self serving behavior Will never admit to own mistakes, faults and shortcomings, and/or refuses to accept criticisms or complaints; Allows his/her judgments and decisions to be unduly influenced by personal feelings and relationships, mood swings, rumors, and the subjective opinions of others; Disparages staff and manipulates discord between them; Places unreasonable work demands on staff. MXCO Hires incompetent people just because they are his/her friends; Manager shows preference for certain employees, and makes arbitrary decisions based on this preference Lacks credibility, says one thing and does another; Blames employees without first investigating the problem; Unfair in the way to apply disciplinary action, tolerates wrongful behavior of employees who are close to him; Gives rude responses and shows arrogance and a bad attitude; Abuse of authority; Ineffective delegation of work, assigning more work to some and less to others. ROMA Treats staff unfairly, unequally and/or with favouritism regarding such matters as the granting of wages and bonuses, approving requests, providing training/promotion opportunities, and/or making judgments about people. Exhibits selfish or self-serving behaviour at the expense of his/her staff; Allows misunderstandings and personal conflict between self and other managers to persist at the expense of full effectiveness and efficiency; Fails to give sufficient advance notice of meetings he/she convenes; Cancels/postpones planned meetings at last minute; Exhibits an inability to admit his/her own mistakes, or when he/she is wrong. CHNA Acts selfishly (-abuses authority for personal gain); Does not evaluate employees in a fair manner; Shows favouritism. CNDA Provides limited opportunities for growth, treated people inconsistently; Provides insincere praise; Spreads the blame but took the praise for themselves; Displays unprofessional showing favoritism, double standards, engaging in questionable hiring practices and taking credit for other’s ideas Private Sector Cases UKF Demonstrates selfish and self-serving behaviours; Shows favoritism and demonstrates double standards in decisions and behaviour; Doesn’t bother to tell staff about meetings they should attend or arrange team meetings. UKG Becomes emotional, irrational or temperamental; Re-arranges/cancels meetings at the last minute. GER Does not treat employees equally/favours certain employees; Criticises in an unfair way/gives unjustified criticism; Ignores work overload, does not respect limited working capacity assigns task despite lack of skills; Does not stick to arrangements, does not keep promises. Third Sector Cases UKH Not considering the impact of their actions on others, and focusing on their own needs above others; Shows a lack of respect and consideration for others, engaging in sensitive conversations and gossip at inappropriate times and places. UKI Disciplines people in an unfair or inconsistent manner. Does not admit to making mistakes; When things go wrong the manager is quick to apportion blame without reviewing the circumstances; Shows a lack of honesty in their dealings with people; Will only listen to those concerns which are in line with their own thoughts; Undermines school processes and agreed procedures by not upholding and following them; Works in a very task focused manner with no regard for people’s feelings; Approaches conflict in a confrontational manner; Note: (i) Those ‘units of meaning’ typed in italics in some of the BSs do not relate to this particular generic behavioural criterion (ii) Details of the positive (effective) generic behavioural criterion Good planning and organizing, and proactive execution, monitoring and control can be found in Hamlin, Patel & Ruiz (2012) Emergence of a ‘universalistic taxonomy’ The vast majority of BSs that constitute the deduced ineffective behavioural criterion Shows lack of interest in or respect for staff, and/or care or concern for their 9 welfare/well being’ describe the absence of the types of effective managerial behaviour reflected by the BSs that constitute the effective behavioural criterion Shows care and concern for staff and other people. Thus, these two criteria could be seen as the polar opposite ends of a single behavioural construct, with the BSs of the effective behavioural criterion being acts that have been committed and observed, and the BSs of the ineffective behavioural criterion being acts of omission. A similar situation applies for the ineffective criterion: Poor planning, organizing and controlling, bad judgment, low standards and/or tolerance of poor performance from others, and the effective criterion: Good planning and organizing, and proactive execution, monitoring and control. Although the ineffective criterion: Inappropriate autocratic, dictatorial, authoritarian and non-consultative, non-listening managerial approach might appear in some respects to be the polar opposite of the effective criterion: Communicates well with staff and keeps them informed, most of the underpinning BSs describe specific acts/actions-rather than failings to act in an expected way-that managers need to avoid if they are to be perceived and judged effective. Hence, what has emerged from our findings is a universalistic taxonomy of ‘perceived managerial and leadership effectiveness’ comprised of eight (8) positive (effective) and six (6) negative (ineffective) generic behavioral criteria, as shown in Text Box 1. Text Box 1 Deduced universalistic behavioural taxonomy of ‘perceived managerial and leadership effectiveness’ Positive (Effective) Generic Behavioural Criteria 1. Good planning and organizing, and proactive execution, monitoring and control 2. Active supportive management and leadership 3. Delegation and empowerment 4. Shows care and concern for staff and other people 5. Actively addresses and attends to the learning and development needs of their staff 6. Open, personal and trusting managerial approach 7. Involves and includes staff in planning, decision making and problem solving 8. Communicates regularly and well with staff, and keeps them informed Negative (Ineffective) Generic Behavioural Criteria 1. Inappropriate autocratic, dictatorial, authoritarian and non-consultative, non-listening managerial approach 2. Unfair, inconsiderate, inconsistent, and/or selfish, manipulative, self-serving behaviour 3. Active intimidating and/or undermining behaviour 4. Slack management, procrastination in decision making, ignoring problems and/ or avoiding/abdicating from responsibilities 5. Depriving and/or withholding behaviour 6. Exhibits parochial behaviour, a closed mind and/or a negative approach. Discussion The key result of our study is the unexpected finding that the type of managerial behaviours that people within and across multiple organizations in seven diverse countries around the globe associate with effective managers and ineffective managers are very similar. This finding raises questions about the validity of claims made by past researchers who have suggested that national specificities, including national culture, have an impact on how employees perceive the behaviour of their managers/leaders (Morrison, 2000), and that this determines whether or not employees will accept and follow the leadership of their managers (Atlas, Tafel & Tunlik, 2007; Brodbeck et al, 2000). On the contrary, our research suggests the 10 specific managerial behaviours perceived as effective and ineffective by people in Canada, China, Egypt, Germany, Mexico, Romania and the UK are very much the same, are described in similar terms, and are not culture-specific to these societies. Indeed, over 94% (n=811) of the behavioural statements indicative of the different types of managerial behaviour that people in these seven countries perceive as differentiating effective managers/leaders from least effective/ineffective managers/leaders, are convergent (universal) rather than divergent (contingent). Another key finding is that there is little difference in the perceptions of ‘perceived managerial and leadership effectiveness’ across organizational sectors. This evidence supports Lau, Pavett and Newman’s (1980) claim that there are similarities between managerial roles, behaviours and activities across organizational sectors. Conversely, it lends little support for those who argue that for managers to be effective in public sector and third sector (not-for-profit) organizations, they need to adopt different managerial behaviours to managers in private sector (for-profit) organizations (see Baldwin, 1987; Fottler, 1981; Peterson & Van Fleet, 2008). Additionally, our findings lend minimal support for Tsui’s (1984) assertion that specific managerial behaviour instrumental for gaining managerial reputational effectiveness will vary by constituencies within [and by inference] across organizations and organizational sectors; or for Flanagan and Spurgeon’s (1996) assertion that managerial effectiveness is “situationally dependent and varies from one organization to another” (p. 96). Although several researchers such as Arvonen and Ekvall (1999), and Dorfman et al (1997), have demonstrated both similarities and differences existing between the perceptions of leadership effectiveness across different nations, our study has demonstrated that there are many more similarities than differences. Our findings suggest universal explanations of ‘perceived managerial and leadership effectiveness’ are more consistent with the facts. It also challenges to some extent the axiomatic belief amongst most international researchers that effective management and leadership processes are contextually contingent and must reflect the culture in which they are found. Limitations of the study There are four potential limitations to our study. First is the fact that of the 15 emic studies from which our empirical source data were obtained, 10 were carried out in public sector organizations, 3 in private (for profit) companies, and 2 in the third (notfor-profit) sector; and overall 9 were UK based,. This means that our deduced generic behavioral criteria may contain an under representation of certain types of managerial behaviour in private and third sector organizations and non-UK countries. Second is the fact that although the number of CIT informants in these 15 past emic studies were within or exceeded the range of recommended sample sizes (n=20 to 40) for qualitative research (Cresswell, Plano Clarke, Gutmann & Hanson, 2003), it is possible there might have been a degree of under sampling in some of the cases. If so, there may be other generic behavioural categories of effective and ineffective managerial behaviour that have yet to be identified. Third, some writers have argued that good organizational performance should not be automatically attributed to effective leadership (Erkutlu, 2008). Similarly, we argue that ‘perceived managerial and leadership effectiveness’, as judged against subjective proximal outcome measures such as the generic behavioural criteria deduced by our study, may not automatically lead to ‘good’ or ‘poor/bad’ managerial performance as measured 11 against objective distal standards. Fourth, although our findings suggest cultural influences within and across nations have limited impact on how people define ‘perceived managerial and leadership effectiveness, additional empirical evidence needs to be obtained from more emic replication studies before one could claim the existence of a stable ‘universal’ or ‘near universal’ taxonomy. Implications for HRD research and practice Of the few contemporary researchers other than ourselves who have explored the behavioural determinants of managerial and leadership effectiveness (e.g. Cammock et al, 1995; Riccucci, 1995; Svara, 1994), even fewer have identified the specific managerial behaviours that managers/leaders need to avoid if they are not to be perceived by their respective stakeholders as being least effective or ineffective (CIPD, 2011; Fernandez, 2005). And of those that have, the focus has been on ‘bullying’, ‘abusive’, ‘harassing’, and ‘toxic’ leadership (Einersen, Aasland & Skogstad, 2007). Our study explored least effective/ineffective as well as effective managerial behaviours, and thereby has made a distinctive contribution to current literature in this area of management research. We find that 6 of our 8 deduced negative (ineffective) generic behavioural criteria do not simply reflect the absence of the type of managerial behaviours identified with highly effective managers/leaders, but rather indicate the active presence of the type of behaviours that their superiors, peers and subordinates (stakeholders) consider inappropriate and ineffective. Thus, our emergent ‘universalistic taxonomy’ provides new insight and a better understanding of the type of specific ‘demonstrated [management] behaviours’ (Ferris et al. 2003) that managers need to avoid or adopt if they are to establish a reputation for managerial and leadership effectiveness. And because our taxonomy contains a rich description of indicative effective and ineffective managerial behaviours observed in public, private, and third sector organizations in seven very different and diverse countries situated across five continents, it is likely to strike a chord with and be easily understood and applied by managerial and non-managerial employees in many other organizations and nations around the globe. Although competency-based HRD/HRM systems serve as a means of measuring and assessing managers and leaders for development, for improving managerial performance, and for managing progression more effectively across a variety of modern organizations (Gold and Iles, 2010), in many cases the benefits either do not materialize or do not match up to expectations. As Hamlin (2010) claimed, many managers find it hard to use competencies to help achieve their own goals and the goals of the organization because, typically, competency-frameworks are either too general or too detailed. When the former, insufficient guidance is given as to the specific types of managerial behaviour critical for success; when the latter, processes become too cumbersome and too time consuming. This can lead to a lack of credibility and then to ‘lip service’ or ‘disengagement’ on the part of hard pressed managers and employees. We suggest a potential solution to this problem could be our emergent ‘universalistic taxonomy of perceived managerial and leadership effectiveness’ because, as outlined above, it specifically identifies the critical managerial behaviours that differentiate ‘good’ from ‘poor’ or ‘bad’ management/leadership practice. Additionally, the taxonomy has the potential to be used by HRD professionals in various organizations and countries to (i) critically review and validate existing managerial competency-frameworks, (ii) refine and 12 enrich the behavioural underpinning of in company taxonomies of managerial effectiveness or leadership effectiveness; (iii) develop management competency frameworks that have international relevance and utility, (iv) shape the creation of better management related development tools such as 360 degree appraisal instruments and self-assessment personal development plans, and (v), inform HRD/OD intervention strategies for bringing about desired changes in an organization’s management culture. Conclusion and Recommendations We have deduced an emergent ‘universalistic taxonomy of perceived managerial and leadership effectiveness’ that has been shown to be relevant, translatable, and transferable across seven diverse countries situated across five continents. However, its relevance and validity in other specific organizational, sectoral and national contexts have yet to be demonstrated empirically. Hence, we suggest further emic replication studies of perceived managerial and leadership effectiveness should be conducted by indigenous researchers in a more diverse range of public (state), private (for-profit) and third (non-profit) sector organizations not only in Canada, China, Egypt, Germany, Mexico, Romania and the UK, but also in many other countries around the globe. The empirical findings of such studies could then be used cumulatively to test and refine the taxonomy through a succession of multiple case, cross-sector and cross-nation comparative analyses until theoretical saturation has been reached, and additional cases do not add anything (Eisenhardt, 1989). This might lead ultimately to the emergence of a ‘universal taxonomy of perceived managerial and leadership effectiveness’. References Anderson, D. W., Krajewski, H. T., Goffin, R. D., & Jackson, D. N. (2008). A leadership self-efficacy taxonomy and its relation to effective leadership. Leadership Quarterly, 19, 595-608. Arvonen, J., & Ekvall, G. (1999). Effective leadership style: Both universal and contingent? Creativity & Innovation Management, 8(4), 242-257. Atlas, R., Tafel, K., & Tunlik, K. (2007). Leadership style during transition in society: The case of Estonia. Problems and Perspectives in Management, 5(1), 50-62. Avolio, B. J., Bass, B.M., & Jung, D.L. (1999). Re-examining the components of transformational and transactional leadership using the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 72(4), 441-463. Baldwin, J. (1987). Public versus private: Not that different, not that consequential. Public Personnel Management, 16, 181-193. Berry, J.W. (1989). Imposed etics-emics-derived etics: The operationalization of a compelling idea. International Journal of Psychology, 24, 721-735. Borman, W. C., & Brush, D. H. (1993). More progress toward a taxonomy of managerial performance requirements. Human Performance, 6(1), 1-21. Braun, V. & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77-101. Brodbeck, F. C., Frese, M., & Akerblom, S. et al. (2000). Cultural variation of leadership prototypes across 22 European countries. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 73, 1-29. 13 Cammock, P., Nilakant, V., & Dakin, S. (1995). Developing a lay model of managerial effectiveness. Journal of Management Studies, 32(4), 443-447. CIPD (2011) Management competencies for enhancing employee engagement: Research insight. London: Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development. Conger, J. (1998). Qualitative research as the cornerstone methodology for understanding leadership. Leadership Quarterly, 9(1), 107-121. Cresswell, J. W., Plano Clarke, V., Gutmann, M., & Hanson, W. (2003). Advances in mixed methods design. In A. Tashakkori & C. Teddie (Eds), Handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioral sciences (pp. 209-240). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Den Hartog, D., Maczynski, J., Motowidlo, S., Jarmuz, S., Koopman, P., Thierry, H. & C. Wilderom, C. (1997). Cross-cultural perceptions of leadership: A comparison of leadership and societal and organizational culture in The Netherlands and Poland. Polish Psychological Bulletin, 28, 255–267. Dorfman, P. W., Howell, J. P., Hibino, S., Lee, J. K., Tate, U., & Bautista, A. (1997). Leadership in Western and Asian countries: Commonalities and differences in effective leadership. Leadership Quarterly; 8(3), 233-242. Easterby-Smith, M., R. Thorpe, R., Lowe. A. 1991. Management research: An introduction. London: Sage. Einersen, E., Aasland, M. S., & Skogstad, A. (2007). Destructive leadership behaviour: A definition and conceptual model. Leadership Quarterly, 18, 207216. Eisenhardt, K.M. (1989). Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review, 14, 532-550. Erkutlu, H. (2008). The impact of transformational leadership on organizational and leadership effectiveness: The Turkish case. Journal of Management Development, 27(7), 708-726. Fernandez, S. (2005). Developing and testing an integrative framework of public sector leadership: Evidence from the public education arena. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 15(2), 197-217. Ferris, G. R., Blass, F. R., Douglas, C., Kolodinsky, R.W., & Treadway, D. C. (2003). Personal reputation in organizations. In J. Greenberg (Ed.), Organizational behavior: The state of the science (2nd ed) (pp. 211–246). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Flanagan, J. C. (1954). The critical incident technique. Psychological Bulletin, 51(4), 327-358. Flanagan, H. & Spurgeon, P. (1996). Public sector managerial effectiveness : Theory and practice in the National Health Service. Buckingham: Open University Press. Fleishman, E. A., Mumford, M. M., Zaccaro, S. J.Levin, K.Y.Korokin, A.L., & Hein, M. B. (1991). Taxonomic efforts in the description of leader behavior: A synthesis and function interpretation. Leadership Quarterly, 2, 245-287. Flick, U. (2002). An introduction to qualitative research (2nd Edition). London: Sage. Fottler, M. (1981). Is management really generic? Academy of Management Review, 6, 1-12. Gibbs, G.R. (2007). Analyzing qualitative data. London: Sage. Gold J., & Iles, P. (2010) Measuring and assessing managers and leaders for development. In Jeff Gold, Richard Thorpe and Alan Mumford (eds). Gower handbook of leadership and management development, (pp.223-241). Farnham, UK: Gower. 14 Hales, C. P. (1986). What do managers do? A critical review of the evidence. Journal of Management Studies, 23 (1), 88-115. Hamlin, B. (2010). Evidence-based leadership and management development. In Jeff Gold, Richard Thorpe and Alan Mumford (eds). Gower handbook of leadership and management development, (pp 197-220). Farnham, UK: Gower. Hamlin, B. & Cooper D. (2007) Developing effective managers and leaders within healthcare and social care context: An evidence-based approach. In Sally Sambrook & Jim Stewart (Eds.), HRD in the public sector: The case of health and social care, (pp. 187-212). London: Routledge. Hamlin, R. G. (1988) The criteria of managerial effectiveness in secondary schools. CORE: Collected and Original Resources in Education, The International Journal of Educational Research in Microfiche 12(1), 1-221. Hamlin, R. G. (2002). In support of evidence-based management and research informed HRD through professional partnerships: An empirical and comparative study. Human Resource Development International, 5(4), 467491. Hamlin, R. G.(2004). In support of universalistic models of managerial and leadership effectiveness. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 15(2), 189-215. Hamlin R. G. and Barnett, C (2011) In support of an emergent general taxonomy of perceived managerial and leadership effectiveness: An empirical study from the UK independent schools sector. Paper presented at the UFHRD/AHRD 12th International conference on HRD research and practice across Europe. University of Gloucestershire, United Kingdom, June. Hamlin, R. G. & Bassi, N. (2008) Behavioural indicators of manager and managerial leader effectiveness: An example of Mode 2 knowledge production in management to support evidence-based practice. International Journal of Management Practice, 3(2), 115-130. Hamlin, R.G., Nassar, M., & Wahba, K. (2010). Behavioural criteria of managerial and leadership effectiveness within Egyptian and British public sector hospitals: An empirical study and multiple-case/cross-nation comparative analysis. Human Resource Development International, 13(1), 43-64. Hamlin, R.G., Patel, T, & Iurac, D. (2010). Behavioural indicators of managerial and leadership effectiveness within Romanian and British public sector hospitals: An empirical study and cross-nation comparative analysis. Paper presented at the UFHRD/AHRD 11th International conference on HRD research and practice across Europe. University of Pecs, Hungary, June Hamlin, R. G., Patel, T., & Ruiz, C. (2012) Deducing a general taxonomy of perceived managerial and leadership effectiveness: A multiple-case, crosssector and cross-nation study of effective and ineffective managerial behavior. In K. M. Dirani, J. Wang & J. Gedro (Eds.) Proceedings of the 2012 AHRD International Conference in the Americas (pp. 177-203), Minneapolis-St Paul, MN: Academy of Human Resource Development Hamlin, R. G., Reidy, M., & Stewart, J. (1998). Bridging the HRD research-practice gap through professional partnership Human Resource Development International 1(3), 273-290. 15 Hamlin, R.G., Ruiz, R. & Wang, J. (2011). Behavioural indicators of managerial and leadership effectiveness within Mexican and British public sector hospitals: An empirical study and cross-nation comparative analysis. Human ResourceDevelopment Quarterly, 22(4), 491-517. Hamlin, R.G. & Sawyer, J. (2007). Developing effective leadership behaviours: The value of evidence-based management. Business Leadership Review, 4(4), 1-16. Hamlin, R. G., Sawyer, J. & Sage, L. (2011) Perceived managerial and leadership effectiveness in a non-profit organization: An exploratory and cross-sector comparative study. Human Resource Development International, 14(2), 217234 Hamlin, R.G., & Serventi, S. (2008). Generic behavioural criteria of managerial effectiveness: An empirical and comparative study of UK local government. Journal of European Industrial Training, 32(4), 285-230. Hooijberg, R. & Choi, J. (1998). The impact of macro-organizational variables on leadership effectiveness models: An examination of leadership in private and public sector organizations. Proceedings of Annual Meeting of the Academy of Management, Public and Nonprofit Division, San Diego, CA: Academy of Management House, R. J., Hanges, P. J., Javidan, M., Dorfman, P. W. & Gupta, V. (2004). Culture, leadership, and organizations: The GLOBE study of 62 societies. London: Sage Knafl, K. A. & Breitmayer, B. J. (1991). Triangulation in qualitative research: Issues of conceptual clarity and purpose. In J.M. Morse (Ed.), Qualitative nursing research: A contemporary dialogue (pp. 226-239). London: Sage Lau, A.W., Pavett, C. M. & Newman A. R, (1980). The nature of managerial work: A comparison of public and private sector jobs, Academy of Management Proceedings, 40, 339-343. Luthans, F., & Lockwood, D. L. (1984). Toward an observation system for measuring leader behavior in natural settings. In J. G. Hunt, D. Hosking, C. Schreisheim, & R. Stewart (eds) Leaders and managers: International perspectives on managerial behavior and leadership (pp.117-141). New York: Pergamon. Madill, A., Jordon, A. & Shirley, C. (2000). Objectivity and reliability in qualitative analysis: Realist, contextualist and radical constructionist epistemologies. British Journal of Psychology, 91, 1-20. Martinko, M. J. & Gardner, W. L. (1985). Beyond structured observation: methodological issues and new directions. Academy of Management Review, 10, 676-695. Miles, M.B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis. Thousands Oak, CA: Sage. Morrison, A. (2000). Developing a global leadership model. Human Resource Management, 39(2/3), 117-131. Morse, J. J., & Wagner, F. R. (1978). Measuring the process of managerial effectiveness. Academy of Management Journal, 21(1), 23-35. Patel, T., R.G. Hamlin and S, Heidgen. 2009. Exploring managerial and leadership effectiveness: Comparing private sector companies across Germany and the UK. Working paper presented at the UFHRD/AHRD 10th International conference on HRD research and practice across Europe, Northumbria University, United Kingdom, June 16 Peterson T. O., & Van Fleet, D. D. (2008). A tale of two situations: An empirical study of behaviour by not-for-profit managerial leaders. Public Performance and Management Review, 31(4), 503-516. Riccucci, N. M. (1995). Unsung heroes: Federal execucrats making a difference. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press. Shipper, F., & White, C. S. (1999). Mastery, frequency, and interaction of managerial behaviors to subunit effectiveness. Human Relations, 52(1), 49-66. Stewart, R. (1989). Studies of managerial jobs and behaviours: The way forward. Journal of Management Studies, 26(1), 1-10. Svara, J. H. (1994). Facilitative leadership in local government: Lessons from successful mayors and chairpersons. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Tett, R. P., Gutterman, H. A., Bleier, A., & Murphy, P. J. (2000). Development and content validation of a “hyperdimensional” taxonomy of managerial competence, Human Performance, 13, 205-251. Tsang, E. K. K., & Kwan, K-M. (1999). Replication and theory development in organizational science: a critical realist perspective. Academy of Management Review, 24(4), 759-780. Tsui, A. S. (1984). A multiple-constituency framework of managerial reputational effectiveness. In .J Hunt, C. Hoskings, C. Schriesheim & R. Stewart (Eds.), Leaders and managers: International perspectives on managerial behavior and leadership (pp.28-44). New York: Pergamon. Tsui, A. S. (1990). A multiple-constituency model of effectiveness: An empirical examination at the human resource subunit level. Administrative Science Quarterly, 35, 458-483 Tsui, A. S., & Ashford, S. (1994). Adaptive self-regulation: a process view of managerial effectiveness’. Journal of Management. 20(1), 93-121. Wang, J. (2011). Understanding managerial effectiveness: A Chinese perspective. Journal of European Industrial Training, 35(1), 6-23. Whitford, S. (2010). Leader effectiveness in a Canadian-owned utility. Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Phoenix, USA, June. Yukl, G., A. Gordon, A., & Taber, T. (2002). A hierarchical taxonomy of leadership behavior: Integrating a half century of behavior research. Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies 9(1), 15-31. Yukl, G. & Van Fleet, D. D. (1992). Theory and research on leadership in organizations. In M. D. Dunnette & L. M. Hough (eds) 2nd Ed. Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology, Vol 3 (pp.147-197). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press. Zhu, Y. (2007). Do cultural values shape employee receptivity to leadership styles? Academy of Management Perspectives, 21(3), 89-90. 17