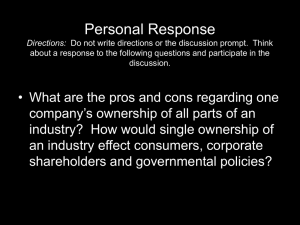

open access to the broadband internet technical and economic

advertisement