Unit 23

advertisement

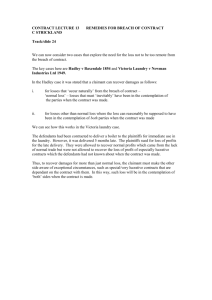

Objective Notes: W300 – Agreements, rights & responsibilities UNIT 23 - MANUAL THREE DAMAGES FOR BREACH 1 How damages for breach are awarded Aim = compensate A, not punish B & losses embrace harm to A’s person/ property & injury to economic position so may claim where suffers PI, goods damaged & loss of profit plus consequential losses; Claims normally on expectation basis - as far as money can so do, A to be placed in same situation, by damages being awarded, would have been in if contract had been performed (Robinson v Harman (1848)), being either (i) difference in value between what A actually received & what should have received or (ii) cost of putting A in position should have been in (cost of cure) but courts also deal with situations where value of B’s promise to A > A’s financial enhancement if contract had been properly perf – e.g. loss of amenity/ consumer surplus despite valuation difficulties (Ruxley Electronics & Construction Ltd v Forsyth [1996]); Alternatively reliance basis – damages awarded to place A in position would have been had contract never been made to cover wasted expenditure including necessarily incurred pre-contract (Anglia Television Ltd v Reed [1972]) &, whilst normally selected when not possible to prove what profit would have been had B perf, court may decide reliance correct (McRae v Commonwealth Disposal Commsn [1951]) but courts can reject where bad bargain meant expenditure already wasted (C & P Haulage v Middleton [1983]); Despite assessment difficulties courts may award damages for lost opportunity even where uncertain A would have won (Chaplin v Hicks [1911]); Traditionally, recovery for mental distress not recoverable (Addis v Gramophone Co Ltd [1909]) but courts may award for injury to reputation (Malik v Bank of Credit & Commerce International SA [1997]), mental distress/ disappointment where contract provides holiday/ entertainment/ enjoyment (Jarvis v Swan’s Tours [1973]), where breach causes physical inconvenience/ discomfort & directly related mental suffering (Watts v Morrow [1981]) & where disappointment results from losing pleasurable amenity important to buyer’s pleasure/ relaxation/ peace of mind (Farley v Skinner [2002]); Remoteness – o By Hadley v Baxendale (1854), losses must be either Limb 1: arising naturally which are inevitably within both parties reasonable contemplation or Limb 2: unusual which only within contemplation if special circumstances giving rise in contemplation when contract made - def must have been told when contract made as such knowledge may affect terms so where acquired, post-contract formation, claimants cannot rely on it; o Victoria Laundry (Windsor) Ltd v Newman Industries Ltd [1949] held may recover losses reasonably foreseeable at time contract made (NB: use of reasonable foreseeability equates contract rule with tort) & def’s knowledge either imputed (that which reasonable persons are assumed to have) or actual - under Limb 1, such knowledge imputed (i.e. def Page 1 Objective Notes: W300 – Agreements, rights & responsibilities 2 taken to know of it) but under Limb 2 too remote unless def has actual knowledge of special circumstances; o But in The Heron 11 [1969], use of reasonable foresight disapproved – contract test is stricter contemplation basis since A aware who B is & has opportunity to point out special circumstances so can ensure recovery in unusual situations by bringing them to B’s attention before making contract; o Where def contemplates loss type being serious possibility, all such losses recoverable even if extent not foreseeable (Parsons (Livestock) Ltd v Uttley Ingham Ltd [1978]). There is duty to mitigate – to ensure losses are kept to minimum & where A could have avoided losses by taking reasonable steps but fails so to do, cannot recover damages for these & where B makes reasonable performance offer, A fails to mitigate if refuses to accept so general rule = (i) reasonable offers from B should be accepted, subject to specific facts involved but where personal service an element, unreasonable to expect A to consider offers from B who has grossly injured him; & (ii) where alleged that A failed to mitigate burden of proof of establishing this on B (Payzu Ltd v Saunders [1919]; Where reasonable mitigation steps increase A’s loss, can recover cost of measures & claim not fail just because def suggests others less burdensome to him could have been taken (Banco de Portugal v Waterlow & Sons Ltd [1932]); Damages assessed as at time of breach & where supervening events cause damage greater than original breach, claimant cannot recover losses would have suffered if event had not occurred so tort principles apply – where there is intervening event which breaks causation chain, no direct link between original breach & actual loss so def not then liab (Beoco Ltd v Alfa Laval Co Ltd [1994]); Damages reduced by contrib. neg where contractual duty to take care is breached, provided breach also = tort – i.e. concurrent liab (Henderson v Merrett Syndicates) - e.g. where def breaches s.13 SOGSA implied skill/ care AND liab in tort for Neg but where contractual liab strict, claimant’s contrib. neg not reduce & no deductions made to reflect his contrib. towards losses (Barclays Bank Plc v Fairclough Building Ltd [1995]. Liquidated clauses/ penalty clauses Parties free to specify amount of compensation payable if contract broken helps provide certainty since shows what payable/ receivable on breach & where both parties content to abide by such clauses, litigation costs avoided; Where genuine attempt to pre-estimate loss likely caused by breach = binding specified damage/ liquidated damages clauses & sum specified paid, irrespective of actual loss, so remoteness, measure of damages or mitigation rules not apply & innocent party may receive more or less than actually lost but sum specified crucial so where clauses are not genuine pre-estimate loss attempts = penalty clauses normally designed to put pressure on parties to perform & are void/ unenforceable – courts free to assess damages, as if clause not there, applying normal rules; Page 2 Objective Notes: W300 – Agreements, rights & responsibilities Whilst prima facie parties mean what say, wording used not conclusive, clause may still be specified damages clause even where impossible to precisely pre-estimate losses & as guideline, clauses presumed penal where (i) sum specified > greatest possible loss; (ii) larger sum payable after nonpayment of smaller sum; or (iii) single lump sum payable on occurrence of one or more of several events of which some may cause serious harm but others only minor (Dunlop Pneumatic Tyre Co Ltd v New Garage & Motor Co Ltd [1915]); Where hypothetical situations showed sums payable might be out of proportion to actual losses, normally insufficient evidence that clause penal, & should be determined by looking at what was parties’ intentions at time contract was made but also important to look at what had actually happened since produces valuable evidence of what could be reasonably be expected to be losses pre-supposed at time contract made- what actually happened was better guide than hypothetical examples (Philips Hong Kong Ltd v A-G Hong Kong [1993]); Where clauses provide payments for events not constitute breach, cannot be held void as penalty clauses (Alder v Moore [1967]); Deposits not penal & are irrecoverable unless court decides sums paid not true deposits &, if so, entire sum (less any damages caused by breach) to be repaid since court will not re-write contract – will not insert reasonable sum which def may retain (Workers Trust & Merchant Bank Ltd v Dojap Investments Ltd [1993]); Where pre-payment deemed part payment, general rule = party in breach may recover (Dies v British International Mining & Finance Co [1939]) unless def incurred expenditure in which case, breaching party may not be able to recover (Hyundai Shipbuilding & Heavy Industries Ltd v Papadopulos [1980]). Page 3