to view

advertisement

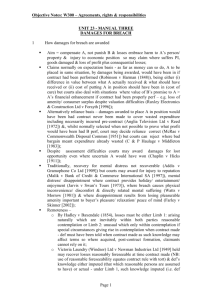

Change Management – A Tool For Success Adam D. Vereshack 2006 Presentation Overview Case Studies h Background h What went wrong h What was the resolution Lessons Learned Practical Contract Considerations h Contractual h Behavioural Theory vs. Reality Summary of Legal Principles 2 Case Studies – A Tale of Two Contracts Contract A – Background h Large multi-jurisdictional Customer h Issued RFP to replace approximately 30 legacy pay and benefits systems with new integrated system (design/build contract) h Fixed price bid was awarded ($67M) and the specifications agreed to in the design phase h After design phase complete, Customer requested almost 100 changes to the specifications during the first nine months of the build phase h Service Provider, in order to be responsive to Customer’s needs, started to make requested changes 3 Case Studies – A Tale of Two Contracts 4 Contract B – Background h Large Canada-wide business h Issued RFI for proposals for an integrated system to streamline the booking and purchase of travel and accommodation for its employees (design/build/run contract) h Fixed Price Bid was awarded ($275M) h Prolonged negotiations during which parties worked out deliverables and service levels h Customer asked for more than 70 changes in the first year of the build phase h Service Provider started to make many of the requested changes as they appeared to be necessary to the core build The Fatal Errors In Both Cases: h The Customer requested changes h The Service Provider made (or started to make) many of them h Both parties ignored the change management process in the contract h As a result, additional costs and impact on implementation schedule were not dealt with by the parties h As a result, since Service Provider did not challenge the requested changes as being out of scope, there was no issue to escalate through the governance process in the contract h As a result, key dates in the implementation schedule were missed 5 Resolution Contract A h Contract was eventually terminated by Customer (purportedly) for cause h Customer claimed breach of contract for delays in implementation schedule h Service Provider claimed breach of contract for changes that Customer refused to pay for h Costly litigation ensued h Dispute eventually settled after several years of hardfought litigation 6 Resolution Contract B h After lengthy negotiations (and delays), most outstanding issues were resolved by amendments to the outsourcing contract h System has now been completed and rolled out to Customer user community h However, costly compromises made in getting to settlement • Services Provider not paid for all changes • Customer missed key dates in implementation schedule 7 Lessons Learned h For Customers – Use change management procedures h For Service Provider – Use change management procedures h Properly drafted, they will address both impact on costs and on implementation schedule h If the change management procedure identifies a “disconnect” between the parties’ expectations, it can be addressed sooner rather than later h Once used with regularity, parties become familiar with the change management tool and are more likely to use it 8 Theory vs. Reality h In fixed price contracts, there is often a defined “funding envelope” that creates limits on the ability of Customer to obtain Board or senior management approval of additional funding h Frequently, Customer doesn’t know exactly what it wants (or needs) h Customer’s specific needs evolve through the life of the project, which naturally generates changes h The Service Provider must walk a fine line between appeasing the Customer’s evolving view of “What It Wants” and ruining its margins on the project 9 Practical Considerations Contractual h Include clear language in the contract whereby: • the parties recognize that changes will have an impact on the implementation schedule • the Service Provider is prohibited from commencing any “new” work unless there is an agreed-upon Change Order • “new” work is carefully defined/delimited • if a sign-off is declined by either party’s Project Manager, there is an immediate escalation (and resolution) using the contract governance process • there are liquidated damages for delays 10 Practical Considerations Behavioural h Recognize that clear functional requirements (what the system does) and clear detailed design specifications (how the system does it) are not enough h Recognize that clear change management contract terms and conditions are not enough h Most importantly, recognize that the parties must use them h Carefully monitor and sign off on any departure from functional requirements or detailed design specifications h Be aware of the any possible “domino” effect of functional or technical changes h Be aware of the cumulative effect of changes in terms of time and money (Sometimes 1 + 1 + 1 does equal 5.) 11 Legal Principles Extras “Whether a particular item is part of the scope of work or an “extra” is to be determined by reference to the terms of the contract, the nature of the work and the surrounding circumstances. Where the additional items are great in number and magnitude, they are likely “extras” and not included in the original contract price.” Reference: Cardinal Construction Ltd. v. Brockville (Municipality) (1984), 4 C.L.R. 149 (Ont.H.C.J.) at 162. 12 Legal Principles Extras “By requesting extra work and by omitting to perform certain obligations, an owner necessarily increases the time for completing a construction contract, and is thereby precluded from claiming penalties for non-completion provided by the contract.” Reference: Ottawa Northern and Western Railway Co. v. Dominion Bridge Co. (1905), S.C.R. 347 at 359. Culina v. Guiliani [1972] S.C.R. 343 at 357. Lafferty v. Ontario Chiropractic Association (1988), 61 O.R. (2d) 754 (H.C.J. at 756-757, aff’d 70 O.R. (2d) 383 (C.A.). S.M.K. Cabinets v. Hili Modern Electrics Pty. Ltd., [1984] V.R. 391 (Full.Ct.) at 394-96. 13 Legal Principles 14 Standards “Where a contract, either expressly or by implication, contains a particular standard or quality for the work to be done, a party is not entitled to insist on work of a different or higher standard or quality.” Reference: Hulshan v. Nickling, [1957] O.W.N. 587 (C.A.) at 590. Legal Principles 15 Payment for Variations “Where the work is greatly in excess of that provided for in the contract, as a result of variations made by the owner, and if at the time of contracting such increased amount of work is not contemplated by the contract, the contractor is entitled to be paid a reasonable profit thereon. If there is no express term in the contract requiring such payment, the Court will imply it.” Reference: Sir Lindsay Parkinson & Co. Ltd. v. Commissioners of Works and Public Buildings, [1950] 1 All.E.R. 208 (C.A. at 227). Cana Construction Co. Ltd. v. The Queen, [1974] S.C.R. 1159 at 1172-75. Legal Principles Payment for Variations “If the scope of the work is significantly changed by the owner during construction, the contractor will be entitled to the increased cost as damages. If no price is fixed for the performance of extra work, the Court will imply a promise to pay reasonable amount on a quantum meruit basis. If the change is by agreement between the owner and the contractor which results in the completion of the contract under totally different conditions, or if the contract has been wrongfully terminated as a result of the owner’s conduct, the contractor may recover the extra costs on a quantum meruit basis. ” Reference: Colautti Construction Ltd. v. Ottawa (City) (1984), 7 C.L.R. 264 (Ont.C.A.) at 272-273. Re: Bailey Construction Co. and The Township of Etobicoke, [1949] O.R. 352 (C.A.) at 358. 16 Legal Principles 17 Delays “Mere delay in completion is not a breach of a fundamental term, even where there is a “time is of the essence” clause, and particularly where there is a liquidated damages clause. ” Reference: G.L.C. v. Cleveland Bridge & Engineering (1984) 34 B.L.R. 50 (C.A.) at 53. J.M. Hill and Sons Ltd. v. London Borough of Camden (1980), 18 B.L.R. 31 (C.A.) at 38ff. Abenstein v. Canada (1990), 34 F.T.R. 116 (T.D.) at p.125-26. Legal Principles 18 Delays “It has been held that an owner waives the right to claim for delay where the delay was occasioned by a request for extra work, unless the agreement expressly gives the owner the right to request alterations while still requiring completion by a specific time. ” Reference: Canada Foundry Co. Ltd. v. Edmonton Portland Cement Co., [1918] 3 W.W.R. 866 (P.C.) at 872; affirming [1917] 1 W.W.R. 382 (C.A.). Legal Principles Delays In Maglario v. Simon, the Court allowed the contractor’s action for damages for breach of contract because the delay was caused unreasonably and, in part, by changes and alterations requested by the owner during the court of the contract. Reference: Maglario v. Simon (1978), 27 N.S.R. (2d) 674 (T.D.) at 680-681. 19 Legal Principles 20 Delays In H.G.D. Enterprises Ltd. v. Leone Industries Inc., the delays by the developer during the course of the contract were not significant enough to warrant termination. The delays attributable to the developer were acquiesced to by the owner, and were the result of modifications to the project requested by the owner. The owner’s constant interventions were, in large part, responsible for the delay. Reference: H.G.D. Enterprises Ltd., v. Leone Industries Inc. (1985), 9 C.P.R. (3d) 553 (B.C.S.C.) at 55ff.