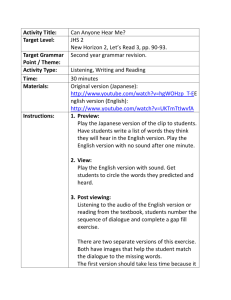

China and major global centers of power 15 11 12

advertisement

CHINA’S FOREIGN POLICY AND THE PROBLEM OF "RESPONSIBLE" LEADERSHIP: RELATIONS WITH MAJOR CENTERS OF POWER China – U.S.: strategic interaction Evolution of the U.S.’s attitude to China. The Obama administration is proposing a new model for the world order – not confrontational "polarity" but "responsible leadership" in resolving globalized problems of security and development. From this angle, the perception of China is also changing to that of a big country rapidly increasing its international weight. For the U.S., China is a potentially of the most important global partners. Yet the new perception of China is laid on top of the traditional one. The essence of the latter is that China integrated into the global economy is seen by the U.S. as an economic rival. Politically, the attitude toward China is determined by the continued monopoly of power by the Communist Party of China, and "Communist government", even if revamped and not totally "Communist", which is seen as undemocratic. Political reforms in China might reduce grounds for such a perception but only very slowly. There will be no major advance here, at least until new leaders come to power in the People's Republic of China in 2012. Nevertheless, China’s growing domestic demand and its positive role in overcoming the global financial crisis in 2008–2009 strengthened its position as a major partner for the U.S. The ambiguous perception of China in the U.S. accounts for the main problem in its policy towards the Asian giant. Washington is unable to balance the two basic approaches to Beijing: one is aimed at cooperation with China and its involvement in resolving regional and global security and development problems, while the other is aimed at restraining China. Hence the ambiguous nature of China-U.S. relations. On the one hand, there arise new initiatives that would probably lead to a breakthrough in the future; on the other hand, elements of irritation with China could be seen in the U.S.: criticism, though often muted, of violation of human rights and raising the subject of democracy; supplies of armaments to Taiwan, though in somewhat reduced quantities; contacts with the Dalai Lama, and so on. In practice, the new model of the US-China "universal strategic partnership" is taking shape neither rapidly nor smoothly. It is not only a matter of traditional points of divergence. Under the current leadership, Beijing is in no hurry to assume too much global responsibility or to specify its strategic vision of a "harmonious world" and "responsible leadership." Neither Washington is ready to place breakthrough ideas in the agenda for dialogue with China. Even so, the U.S.-China relations under the Obama administration have reached a new level. The previous format of "economic dialogue" accepted by George W. Bush has been supplemented with a strategic component of "strategic and economic dialogue." This is broadening the discussion agenda by adding issues of global and regional security. China is endeavoring to use the new version of strategic dialogue for studying in detail the US economic and political models by sending hundreds of high-level officials to various events held in the United States. In its turn, America aims to prompt China to adopt basic elements of the U.S. system as a guarantee of American security in the future. Among the regional problems, the U.S. seeks support from Beijing in tackling North Korea nuclear and missile problems. The U.S. approach aims at converting China into main player in this matter. Washington is even prepared to sacrifice some elements of its relations with Seoul – its main ally in Korean affairs. For example, in mid-2009, President Obama supported Lee Yong Bak’s initiative of continuing the six-party talks even without North Korea. China opposed this. Since 2010, Washington has not been pushing this matter looking up to Beijing and its latest ideas including the $10 billion fund being set up by China for investing in North Korean infrastructure and market reforms. The worsening of China-U.S. relations in connection with supplies of armaments to Taiwan was a temporary one. This merely slowed down the development of China-U.S. military cooperation, regarding which the Chinese top brass have opposing views. It is noteworthy that official Beijing which sharply criticized the supplier mentioned nothing about the buyer of the arms – Taipei. This fits in with China’s current course toward engaging Taiwan intensively and deeply in economic terms, which in the future will allow the mainland to restore its sovereignty over the island peacefully. Such scenario is strategically acceptable to the U.S.. In the economic sphere, protectionism in relation to China has been replaced by the idea of coordinating economic strategies by Beijing and Washington. The United States continues to exert pressure, though moderated, on China regarding "revaluation of the yuan" and the U.S. trade deficit and to prevent China from buying up U.S. assets. Yet Washington’s stance is shifting toward resolving these problems through dialogue and compromise. In its turn, China, having consolidated its positions, is now more than ever prepared for strategic interaction with the U.S. Yet globally significant breakthroughs are only likely after 2012. Chinese leaders prefer to pass on to the next generation the burden of responsibility for both domestic political reforms in China and foreign policy changes. So far, we see potential for strategic interaction between China and the United States and development of mechanisms for adapting traditional areas of conflict to it. This trend does not create any new military threats for Russia. However, first, it makes it counterproductive to attempt playing the "China card" in relations with the United States or to seek ways to jointly “contain” China. Secondly, it creates the risk of becoming marginalized on both regional (Trans-Pacific security) and global scale. The way out for Russia lies in joining the newly forming China-U.S. partnership by initiating creation of a strategic "triangle" of Russia, China and the United States. China’s policy vis-à-vis the U.S. China’s strategic efforts are focused on strengthening its global political positions and positions in the sphere of security on the basis of its economic power and expansion which gained impetus during the global economic crisis, and the positive image gained by China over the last two years as its domestic demand and financial assistance helped the global economy and individual countries in overcoming the crisis. In realizing its serious strategic ambitions China may come into conflict with world leaders over specific global or regional problems of security. Yet it will strive to avoid exacerbation of the situation even if its strategic interests are affected, directly or indirectly (for example, in the event of Russian-American cooperation on ABM). Through expert community channels ("track 2") China will let Russia know that it is concerned about the latter’s cooperation with the U.S. and NATO on ABM and will speak of the need to know more about the details of such cooperation. In this format the question may be raised unofficially that China is concerned about Russia’s cooperation with the U.S./NATO on ABM and regards it as a threat to its own security, is concerned about expansion of NATO’s military infrastructure at China’s borders, and so on. After the coming change of China’s leadership in 2012-2013, revision of China’s policy on many issues is likely, including the issues of strategic security and antimissile defense. Readiness for cooperation will remain, but Beijing will assert its position more strongly and react more sharply to what it regards as concerns, including ABM. Thus China is likely, on one hand, to increase efforts to create its own ABM system, and, on the other, to intensify its dialogue with the United States on military issues: not on ABM directly, but on confidence-building measures, joint steps to counter new threats like piracy, terrorism, and so on. China may also agree to a dialogue with NATO, to seek what it considers to be important issues leading to real partnership to supplement economic ties with the U.S. and the EU (see below). One more sensitive topic is China’s possible interest in dedollarization of the world economy. Neither official authorities in China nor authoritative economists are seriously considering the possibility of a collapse of the US dollar, its exclusion from the international currency clearing system, or sovereign default of the United States. Such arguments are characteristic of a number of Chinese (and Russian) economists holding alarmist and anti-American views. Collapse (purely theoretical) of the dollar and sovereign default of the U.S. are contrary to China’s national interests for philosophical, conceptual, financial, economic and foreign policy reasons. The Chinese leadership relies on the following chain of reasoning: stable power of the Communist Party of China depends on the country’s political stability, political stability is largely dependent on social stability, social stability is conditional on economic growth, and one of the main conditions for economic growth is stability of the world economic and financial system. Hence, any events that sharply disrupt the global financial stability (landslide dedollarization, sovereign default of the United States, and so on) are perceived by Beijing as a direct threat to its national economic growth and, consequently, going back along the chain of reasoning, to the power of the Communist Party of China. The predominant part of China’s foreign trade, foreign investments in China and Chinese investments abroad is denominated in U.S. dollars. China is the biggest holder of U.S. treasury bills, which constitute almost a third of its foreign and gold reserves. In the event of a landslide dedollarization of the global economy (it is important to stress that this is only a hypothetical situation), China would be deprived of its lever for bringing pressure on the U.S. A sharp change in the role of the U.S. dollar in the financial backup for the Chinese economy, would, Beijing believes, create uncertainty and risks with respect to stable economic and financial interaction between China and the global economy. In the foreign policy sphere, the relations between China and the U.S. are characterized by rivalry and cooperation. This ambiguity tends to strain political relations: an enormous U.S. trade deficit with China and an "inflated" yuan exchange rate. Beijing considers a sharp revaluation to be unacceptable since it would involve many risks for the Chinese economy. . China, in turn, directly accuses Washington of what China sees as an ineffective monetary policy. On the other hand, China is redistributing its financial risks and diversifying gold and currency reserves and foreign transactions. It is doing this through a gradual transition towards extended basket of currencies, which, in addition to the U.S. dollar, includes other convertible currencies, among them “second tier” currencies (the Australian dollar, and so on). In this sense, China is working on a gradual reduction in the role of the U.S. dollar for its economy. Yet the purpose here is not to make any "financial blow" against the United States, but to diminish external financial risks for China itself. China intends, in time, to turn the yuan into convertible currency with a global role comparable with that of the leading "second tier" currencies – British pound sterling, Japanese yen and Swiss franc. Yet China is not speeding up this process and is not setting any specific time goals. Another line of the China’s policy in this sphere is a gradual internationalization of the yuan. China made good use of its contribution to overcoming the global crisis by strengthening its own positions in global finance – in particular, by granting a number of countries trade credits in Chinese yuan. China has its own plans for revaluation and internationalization of the yuan, its own policy for diversifying financial risks. Here, in the political sense, Russian help is not needed. China might use Russia to support Beijing's positions in the dialogue with the financial G-7. Yet, as the internationalization of the yuan proceeds, the financial interests of Russia and of China will diverge. China and the European Union: an emerging partnership The cooperation between China and the European Union (EU) has been characterized over the last decade by both negative attitudes – as was observed after the events in China in 1989 – and a growth of mutual interest. The clearest example of this is the decision to establish a strategic partnership, adopted by the parties in 2003. However, they saw the concept of such partnership differently. Whereas Brussels gave priority to the process of democratization of the political institutions of the People's Republic of China and observance of human rights by its authorities, Beijing stressed more active technological cooperation. This factor has been largely responsible for conservation of old contradictions in the relations between Beijing and Brussels and the emergance of new ones. The clearest examples are as follows. First, major disagreements between the parties in the political sphere are far from being settled. This refers to two interlinked issues –European Union’s embargo on arms supplyies to China and observance of human rights in the People's Republic of China. The European Union links lifting its ban on arms exports to China to China’s complying with number of additional requirements. The latter include improvement of relations with Taiwan, an amnesty for the participants in the events on Tiananmen Square in 1989, and others.1 Meanwhile, different opinions on the issue of human rights in China today have actually intensified after visits by the Dalai Lama XIV to European countries, as well as the decision of the Nobel Prize commission to award the Peace Prize to Chinese dissident Liu Xiaobo, who is in prison in China. The "compensatory potential" of the factors working in favor of the People's Republic of China drawing closer to the European Union proves somewhat inadequate for resolving these specific 1 EU Could End China Arms Embargo In Early 2011. Agence France-Presse. 30 December 2010. disagreements. And these factors are quite substantial: they include similar ideas by Beijing and Brussels on the need for greater polycentricism in the system of international relations; similar positioning modernization models ( Europe’s "soft power" and China’s "peaceful rise"); economic and moral and assistance rendered by China to Greece and Portugal. Second, the parties do not apparently quite understand how to achieve a mitigation of their differences on economic cooperation. While the volume of trade between China and the European Union rose from €212.3 billion to €394.9 billion in 2005–2010, European Union’s trade deficit amounted to €108.5 billion and €168.7 billion, respectively.2 The Europeans view "undevalued" yuan as a problem and hope to resolve it through bilateral interaction with China and multilateral dialogues. Also important is lessening complementarity of economies of China and united Europe. The kind of complementarity relying on China’s cheap labor and European capital and technologies is becoming a thing of the past. China is developing high-tech sectors and makes efforts to foster domestic demand as the main factor of its economic growth. China is also growing aware of the limits of export-oriented model of economic growth. Finally, another serious source of conflict are the results of global financial and economic crisis of 2008–2009, when the West suffered serious "reputation" losses in the eyes of the developing countries, whereas China proved itself quite capable of dealing with economic disturbances. 2 http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2006/september/tradoc_113366.pdf Fig. 2.2.8. China-EU trade, 2005–2010 Chinese exports Chinese imports Trade balance Source: Complied from: EU – China Trade Statistics. This means that the Chinese model of modernization is becoming more attractive for the developing countries than the Euro-Atlantic one. In the "historical competition" with the Europeans, the Chinese are increasingly gaining the initiative. On the whole, in assessing the relations between China and the European Union, it may be concluded that they are, at the current stage, characterized by a strengthening of both cooperation and the confrontation components. Hence the growing uncertainty of the scenarios for development of their relations in the near and medium-term future is arising. Yet there are reasons to expect China to remain a political rival to the Europeans and a more independent and self-sufficient factor in the economy, and the Europeans will have to get used to it. China – Japan: cooperation within the scope of rivalry The logic of cooperation and, at the same time, rivalry remains the key to understanding the essence of the interaction between China and Japan in absolutely all spheres of international relations, including humanitarian aspects. In the area of economic ties, China and Japan are and will remain for each other vitally important international partners and powerful drivers of economic growth. The scale of trade between the two countries has grown immensely over last two decades, topping $300 billion in 2010 and showing exceptional dynamism (Fig. 2.2.9). $ billion Fig. 2.2.9. Dynamics of commodity trade between China and Japan Imports by China from Japan Exports by China to Japan Source: http://www.jetro.go.jp/news/releases/20110217384-news Annual Japanese investments in China stay at a high level, a significant part of them consisting of investments in Hong Kong (Xianggang) (Fig. 2.2.10). $ billion Fig. 2.2.10. Japanese direct investments in China Total Including Hong Kong Source: Calculations by the Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO) based on balance of payments data (http://www.jetro.go.jp/world/japan/stats/fdi/). For China, relations with Japan is an important policy tool for promoting business activity in the country. Even though Japan’s share of China’s foreign trade has been falling in recent years, it remains the country’s main trading partner (alongside the USA and Europe), a key foreign investor and supplier of technology, as well as a counterpart in promoting Chinese products in third countries. For Japan, the People's Republic of China is an important production and resource base for transnationalization of Japanese business, as well as a growing market for its technological products. Even the growth of China’s political ambitions and the tendency towards a toughening of its positions on disputable aspects of bilateral relations, including the territorial one, is not able to change the generally positive attitude of Japanese business towards locating its sales divisions and production sites in China. The latter have become the main driver of bilateral Japanese-Chinese trade, replacing previous more simple forms of trade, mainly in finished products. In Chinese imports from Japan there has been an increase in the share of machinery and capital equipment, as well as parts and units for assembling.3 3 See 2010 Japanese-Chinese Trade in 2010. Press release of the Japan External Trade Organization of 17.02.2011. Traditional trade in consumer and investment goods on the basis of cost advantages also retains its position. Against the background of large-scale transformations taking place in the country’s economy, China retains its advantages for Japanese. At the same time, the significance of specific individual factors changes: previous perception of the People's Republic of China as a reservoir of extremely cheap (considering its quality) labor is becoming a thing of the past. China’s accelerated economic growth is creating a local market of increasing value, which has already become the main incentive for many Japanese companies to transfer part of their business to the People's Republic of China. New opportunities for strengthening the elements of complementary cooperation are offered by exacerbating environmental problems in China as the industrial sector of the economy grows. Impact of mass industrialization on the environment and living conditions in big cities is compelling its government to select technologies reducing damage to the environment. Japanese companies, which have long been operating under conditions of "environmentally friendly" economic activities being the national idée fixe, can offer China many unique "green" technological solutions. At the same time, the scope for interaction in other business spheres, above all in the financial sector, remains limited and rivalry is intensifying. The government of the People's Republic of China is doing all it can to support long-term development of its own banking sector and is jealous of attempts by Japanese financial groups to consolidate their positions in China. Recognizing that the financial sector, on the one hand, is the most profitable and promising link in the "post-industrial" economy, the Chinese authorities are endeavoring to prevent foreign financial institutions from dominating its own financial sector. At the same time, China encourages itscompanies and investment funds to acquire foreign financial assets, including shares in foreign companies and financial institutions. The government of the People's Republic of China itself, within the scope of its diversification of its gold and currency reserves, is increasing the share of Japanese securities, mainly yen-denominated government bonds.4 4 See http://russian.china.org.cn/exclusive/txt/2011-05/20/content_22602302.htm While actively developing foreign investment, including financial investment, the Chinese authorities are still aware that they are ideological and politically "alien" to the West, to which Japan belongs. Although Japanese public opinion is much less (if at all) concerned about human rights and democracy abroad, in the event of any serious cooling of relations between China and the U.S. and Europe, the Japanese government will undoubtedly be compelled to join the threats and sanctions likely to be imposed by the West in this case. The Japanese elite, in turn, is apprehensive that China’s increased confidence of its economic might will make it less prepared to take into account the interests of Japanese business in China, let alone abroad. Even so, there are elements of cooperation and partnership between the two powers on the issue of restructuring international financial system after the global crisis of 2008–2009. Japan shares China’s wish to reduce the role of the U.S. dollar as the international reserve currency and to strengthen regional mechanisms for regulating financial markets in Northeast Asia. Both countries also support the ideas of restricting the scale of speculative operations on global commodity markets, above all those of oil and foodstuffs. Yet there also exist real contradictions between China and Japan. Although the Japanese government, in contrast to the U.S. does not focus on the problem of undervalued yuan, it does demonstrate growing irritation with China retaining elements of currency control, above all for capital transactions .5 Japan also views with apprehension China’s attempts to increase the international status of its currency, in particular to use it in trade with some of its trading partners, as well as for loans extended as assistance to developing countries and promoting Chinese foreign investments. Objectively, the interests of China and Japan in the future architecture of the Asian financial markets diverge: each of the two countries claims the role of regional leader, attempting to boost international significance of its own stock markets and other elements of the financial infrastructure. Both countries would like to take on the burden of economic leadership in Asia, presupposing maximum use of its own institutional and financial infrastructure for organizing international capital markets in this part of the world. On the other hand, the idea of drawing a larger proportion of international financial operations to Asia (as a counterweight to the traditional dominance of Euro-Atlantic capital markets) allows both countries to take common or coordinated positions on many matters. Both countries are inclined to support regionalization of the current international financial architecture, which both China and Japan see as a hangover from the post-war U.S.-centric model of the global structure, no longer appropriate to the realities of the 21st century. Complex relations of cooperation and of rivalry between China and Japan is also an obstacle to efforts to create an institutional infrastructure for regional economic integration – both in the framework of the Pacific Asia, and in a wider format, with the U.S. and other countries with interests in the Pacific region. Claims by both countries to play the role of leader in formulating and expressing the interests of the countries of EastAsia, as well as of the driver of economic growth in this part of the world, impede 5 Nikkei.com, 14.01.2011. them in achieving practical progress in reducing the barriers to cross-border movement of economic resources at the regional level, as a counterbalance to global economic liberalization.6 At the same time, China and Japan are in agreement on their striving to avoid participation in any integration associations in the Pacific which would substantially restrict their economic sovereignty. While expressing support for the idea of lowering barriers to trade and investment between the countries of the region, both countries are fairly categorical in not accepting even partial transfer of customs and currency regulation to any supra-national bodies or structures, especially with the participation of the U.S.7 A similar picture can be seen in the political sphere where cooperation stands side-by-side with fierce rivalry and serious mutual mistrust. On the one hand, China and Japan, recognizing their mutual significance as economic partners, maintain a constant political dialogue and avoid situations when disagreements between them on various matters might seriously spoil the climate of bilateral business contacts and economic interaction. It is now a ritual during political summits to express readiness to make all possible efforts to develop friendship and cooperation between the two countries. Apart from that, the growing dissatisfaction of Japanese political elite with the role of a permanent U.S. debtor assigned to Japan by the U.S. is pushing Japan to coordinate its positions on many global issues with the People's Republic of China. China’s appeal for democratization of the world order meets sincere response in some high-status Japanese politicians, even if they try to avoid formulating their own attitude in such strict and definite expressions as Chinese diplomacy does. On the other hand, there are political contradictions between the People's Republic of China and Japan that spark tension in their mutual relations: – the continuing territorial dispute over jurisdiction over the Senkaku (Diaoyutai) Islands, with related incidents regularly raising the temperature of anti-Japanese moods in the People's Republic of China, including at not only the official but also the popular level;8 – the extreme wariness of each of the two countries of increasing military potential of its counterpart; – political ambitions of each of the two countries, which both claim the role of regional superpower in the Pacific Asia; – different approaches of the two countries to certain problems of major significance in the eyes of either the Chinese or the Japanese side. Thus, Japan’s tacit recognition of India’s nuclear status, its ambiguity over the Tibetan issue, maintaining active contacts with Taiwan and efforts to expand the practice of participation by 6 For example, the Japanese government allocates funds for programs to assist the countries of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations in "rationalization" of their customs tariff system by bringing it in line with Japanese practice (Nikkei.com, 02.05.2011). 7 Nihon Keizai Shimbun, 27.10.2010. 8 Nihon Keizai Shimbun, 30.10.2010. Japanese military in international "peacekeeping operations" are irritants for the People’s Republic of China. A similar situation can also be observed in the cultural sphere of relations between the two countries. In effect, here we have a complicated cocktail of diverse connections and feelings, including elements of historical rivalry, jealousy and mistrust combined with a sense of geographical and ethnic proximity and a certain cultural commonality. Equally ambiguous are the trends that can be observed in this sphere over the last few decades. First, against the background of globalization and expanding political and economic links and interests of China and Japan, there is a growing sense in both countries of the two Asian powers belonging to a single cultural and ethnic community, to a certain extent in opposition to the other global centers of power. Second, with the growth of overall well-being and general liberalization of public life in the People's Republic of China, there has been a sharp increase in the volume of all sorts of informal, including personal, links between the two countries; ideological restrictions have lost their impact to a considerable extent. Third, growth of incomes in China is erasing the sort of sympathetic and patronising attitude that predominated at one time in Japan towards the Chinese as poor relatives in need of assistance and friendly advice. Fourth, in China there is a growing sense of the country being a great power capable of being on an equal foot with the U.S. and Europe. Against this background, Chinese political class is particularly sensitive to the increasing striving on the part of Japan to revise assessment of historical events of the 1930s – 1940s allegedly imposed on it by the winning powers at the end of the Second World War, which is deemed self-humiliating for Japanese national consciousness. However, the basic commonality of economic interests usually overrides negative emotions also in this area, so that cultural and historical disagreements are incapable of spoiling the general atmosphere of the bilateral ties in the long run.