BOOKJUNE08

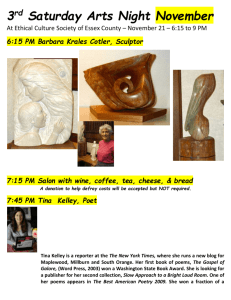

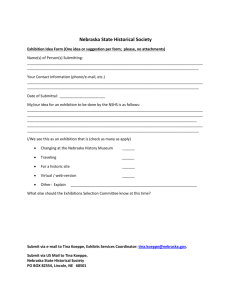

advertisement