22. The Rise of Germany

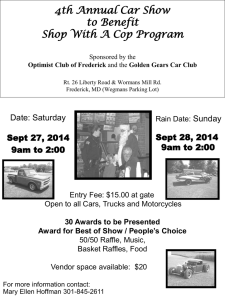

advertisement

The Rise of Germany German history was taboo for most of the 20th century because of the German nation’s involvement in World War I and World War II. Such events as the Holocaust cast a pall over the German people for a period of time in which they themselves repudiated their own history. The rise of Germany as a nation, however, is a fascinating study and unique among our other European nation studies. We will trace German history from 222 BC when Rome first clashed with “Germans” to 1250 AD and the death of a man you’ve already met, Frederick II (Stupor Mundi). The unique aspect is that during this entire period Germany never made it as a nation in the way that England, France, and Spain did. The political history of Germany did not get off the ground until nine centuries after the death of Julius Caesar when it became a part of the Empire of the West under Charlemagne. The barbarous origins of the German people are evident even in their name which is a Celtic term that means, “The shouters.” Julius Caesar borrowed this word to use for his Commentaries on the Gallic Wars. In Latin, the word Alemanni was applied to what actually were dozens of tribes including the Angles, Saxons, Teutons, etc. Germanic tribes were located around the L-shaped formation of the Rhine and Danube river valleys and were distributed, interestingly, by hair color. Red-haired Germanic tribes lived in the north, blonde tribes in the center, and brunettes in the south. Is it proper to refer to barbaric tribesmen as “brunettes?” Nevertheless, Germanic tribes advanced along these two river valleys and shouted at the Celts driving them away to England and Iberia. German expansion ran smack into the Roman Empire in 222 BC and some tribes were annihilated by Roman legions. In 107 BC, however, Germans destroyed four Roman legions. By now you can surely predict Rome’s response—in 101 BC, 55,000 Roman soldiers attacked again, and this time even German women joined in the fighting! Rome prevailed and carted off thousands of males into slavery, but the women killed their children and themselves. Germanic tribes were so warlike that their tribal names were taken from their weapons. The Franks fought with a battle axe called a francisca. The Saxons used a single-edged sword called a saxe, and the Angles preferred an angon, or javelin. Germanic religion was animistic, or based on worshipping spirits in nature. A list of some of their gods makes apparent a degree of influence their religion had on Western civilization—Tieu was the god of war; Woden had created mankind; Thor was the god of Thunder; Friga was the god of love and marriage; and Saturn was the god of time. Maybe that’s why you go out on dates on Friday night and Saturdays seem so short. If one worships the moon on Monday and the sun on Sunday, then there’s Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday to worship these others. What’s more, Easter was Thor’s wife and goddess of rain, and Yule was the god of hunters. Rome’s relationship with Germanic tribes was never settled. The Rhine and the Danube were always battle frontiers with intermittent subjection of certain tribes, but never all the Alemanni. Whenever a coalition of several tribes formed, the Romans were driven back. The great migration of Visigoths, Ostrogoths, Vandals, Lombards, and Jutes in the late 4th and 5th centuries AD totaled around two million Germans who swept over the crumbling Roman Empire. Angles and Saxons went, of course, to England. Charlemagne’s empire engulfed the Germans, converting them and their immediate neighbors, the Magyars, to Christianity and tying them to the West. You remember the Treaty of Verdun in 843 and a man known as Ludwig the German who inherited the eastern portion of Charlemagne’s holdings. In the absence of Charlemagne, however, Germany adopted the feudal system along with the other remnants of the Carolingian Empire. Instead of counts the Germans had dukes, so the land was divided up into duchies rather than into counties under the loose control of the first German king, Conrad I (r. 911-919). A nation seemed in the making. His son Henry I (r. 919-936) launched Germany on a 10-point plan of centralization and dominance that included 1) pacify the Hungarians (Magyars), 2) make the King the master of the dukes, 3) make the King master of the Church, 4) gain control of Italy, and 5) create an empire which would be ruled by Germans and the last large power structure over Europe until Napoleon. Henry I did not accomplish any of these five or the rest of the ten points, but what a vision! Henry’s son Otto I (r. 936-973) did accomplish many of these goals so he got to be remembered as Otto the Great. Otto I asserted more control over rival dukes and finally destroyed all Magyar resistance in 955 thereby creating the boundary with Hungary. He also took upon himself lay investiture, the power to appoint German bishops. In trying to assert control over Italy, he marched on Rome while removing a rebellious duke. During the clash, Otto protected Pope John XII who gave Otto a crown in gratitude. The scene re-enacted the crowning of Charlemagne although I don’t believe it was on Christmas Day. He did get a title, “Emperor of the Romans and the Franks.” One year later, Otto the Great was strong enough to depose Pope John XII for conspiring against him. When Otto I died, however, Germany was still not completely centralized, and Italy proved to be too much for most German kings to handle. Even Otto the Great refrained from trying to control France. A whole series of Ottos, Henrys, and another Conrad all tried to hang onto what Henry I and Otto I had set Germany out to do. Let’s touch on a few of these kings to identify interesting or momentous milestones. Otto III in 998 claimed he was the Western equivalent of the Byzantine Emperor. When he died, however, the Saxon dynasty ended. Henry II (r. 1002-1024) began a new dynasty called the Salian which would produce three more Henrys and rule Germany for over a century. Henry III (r. 1024-1056) used the Cluniac reform movement in 1046 to depose one Pope, Gregory VI, and to install a Cluniac Pope as a zealous reformer. The Cluniac Popes became so powerful that every subsequent Emperor of the Romans and the Franks would try to depose them. If that is not confusing enough, civil war erupted in the 11th century that saw three Popes in a row excommunicate Henry IV (r. 1056-1106) until, remember, his penance in the snow at Canossa. Once restored to the Church, Henry IV drove Pope Gregory VII (Hildebrand) into exile and set up the anti-Pope Clement III. In the conflict, Rome was burned in 1084 by Sicilians trying to rescue Gregory VII. Henry V, the last of the Salian dynasty, died in 1125 after choosing Frederick Hohenstaufen to succeed him. The dukes, however, chose another man, Conrad III (r. 1138-1152) who almost ruined the empire completely by going on the 2nd Crusade (11471149). Conrad’s army was decimated which allowed the empire to fall into another civil dispute; enter again Frederick I to start the Hohenstaufen dynasty. Frederick I, whom you know as Barbarossa, reigned from 1152 to 1190 and was destined to found the most conceited of all medieval dynasties. He also committed what I consider the most heinous acts any ruler claiming to be a Christian has ever done. While assailing Crema, a walled town in Italy, he tied prisoners to his siege engines to prevent their being fired upon. When the walls proved impregnable, he fired prisoners against the walls. When the people of Crema still refused to open the gates, Frederick put children prisoners in his siege engines and fired them against the walls. Crema quit, then. As Frederick I solidified his control he gave the feudal system in Germany hereditary lineage. He married into possession of Sicily. After invading Italy he made peace at last with the real Pope, got his son crowned co-emperor of what he was the first to call the Holy Roman Empire, subdued his most unruly vassal (Henry the Lion), and then at the age of 70 went on the 3rd Crusade. I wonder if he thought of those children in the trebuchets while lying facedown in the river drowning. But the Empire was weakened under Henry VI (r. 1190-1197) because of Frederick’s treaties with Italians of the Lombard League, a confederation of towns in northern Italy, and with the Pope. A period of further civil strife followed the death of Frederick’s son, Henry VI. Frederick’s grandson was only three when his father died, but that boy eventually attained the crown by becoming a vassal to Innocent III, the most powerful Pope of the medieval period. He was crowned Frederick II (r. 1215-1250), but took the name Stupor Mundi. Frederick II, the German Holy Roman Emperor, favored Sicily saying, “It is impossible that the God of the Jews would have so praised the land that he gave his chosen people had he only known the kingdom of Sicily.” Germany had produced an apostate Holy Roman Emperor! Frederick also said, “The world has permitted itself to be duped by three deceivers—Jesus Christ, Moses, and Mohammed.” But with a “Christian” grandfather like Barbarossa, how could one not turn out to be a cynic? Frederick II called Sicily the Fortunate Isle and refused to include it as part of the Empire, merely ruling it separately while living there. He basically let Germany go, even appointing his son Henry as king there while remaining absent for fifteen years at a time. All the while he used the wealth gleaned from Germany to maneuver for Sicily against Gregory IX, a Pope consumed by two passions—love of the Church and hatred for Frederick II. As you have seen, Gregory excommunicated Frederick several times for his behavior on the 5th Crusade (Why would an apostate go on crusade in the first place?). Frederick returned the animosity as evidenced by his message he sent to Gregory when the Pope lay dying. Frederick II, Stupor Mundi, sent the following verse which he composed himself: “I am Frederick, the Hammer, the Doom of the World./ Rome tottering long since, to confusion is hurled,/ shall shiver to atoms and never again be Lord of the World.” Meanwhile, Germany as a nation was barely surviving against renewed pressure from Magyars and from Mongols. Frederick II was distracted from being the Holy Roman Emperor in the tradition of a Caesar or being ruler of a unified German nation. The Holy Roman Empire disintegrated, and there was no German nation to replace it. Other dynasties claimed rule over the Holy Roman Empire, but Central Europe unraveled into several competing states not consolidated into a nation until 1870 by a man named Bismarck who worked for the Hohenzollern dynasty. More on him later.

![Sample Essays [Monarchy, Exam 1]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/008064670_1-abae5bd9813f6a4aa5cf1ba0adf10c38-300x300.png)