A NOTE ON THE ACQUISITION VALUATION PROCESS

In theory, valuation of a company can be based on a wide variety of models

ranging from highly analytical to highly intuitive.

In practice, valuation of acquisition and divestiture targets results from one

or a combination of three methods:

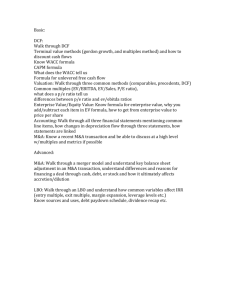

1. Comparable companies

2. Comparable transactions

3. DCF spreadsheet methodology

Comparable Companies And Transactions

The comparable methods have a significant limitation in that finding a broad

sample of fully comparable situations is difficult and often impossible. Also,

they can produce a high dispersion of results as several financial

relationships are frequently compared in the comparable companies

approach.

In class the comparable companies and comparable transactions approaches

were illustrated by Charts 1 – 8 in the attachments to this Note as presented

in Chapter 8 of Takeovers, Restructuring, and Governance by J. Fred

Weston et al., Pearson Prentice Hall, 2004, 2001.

DCF Spreadsheet Methodology

Although based on historical financials, the DCF spreadsheet methodology

essentially looks forward in projecting cash flows for a defined period

(usually 3 to 5 years) post acquisition. Unfortunately, any confidence

generated by “tons” of Excel spreadsheet data can be highly misleading as

results are materially influenced by human variables such as forecasting and

residual value assumptions. DCF results are typically tested against

minimum IRR hurdles. Not infrequently, hurdle requirements lead to

excessively unrealistic projections.

Approaching valuation with a DCF spreadsheet methodology (net present

value(NPV) analysis or internal rate of return(IRR) analysis) has three

critical elements:

1. Building a forecast model

2. Determining residual value

3. Calculate the WACC

Attachment Chart 10 provides an overview of the DCF approach and Chart

10 offers a practical “snapshot” of a representative analysis.

Building A Forecast Model

The process begins with a highly detailed examination of several years of

prior and current financials to understand factors useful for forecasting

including (but not limited to):

Balance Sheets

Excess cash and investments

Receivables: aging, write-off experience and reserves

Inventory: valuation methods, write-off experience,

levels, turns and reserves

Other assets: securities, notes and intangibles

Liabilities: stated, understated, unstated and contingent

Income Statements

Revenues: recognition policies and trends

Gross and operating margins and trends

Impact of inventory and depreciation methods

Incidence of “owner’s perks” i.e. non-essential

Salaries, pensions, travel, automobiles,

airplanes, insurance, payments et al.

The process continues with a review of macro-economic and applicable

industry conditions, forecasts and studies along with an understanding of

competitor’s financial results and strategies.

The objective is to determine the target’s quality of earnings as a

fundamental basis of developing the profit plan forecast model.

Building a realistic earnings model:

Incorporates anticipated economic and industry events

Builds upon prior results carefully adjusted to reflect the

new realities post acquisition

Adds back the net costs of owner’s perks reflecting any

new costs needed to replace prior management

Includes supportable positive and negative synergies

Schedules anticipated capital expenditures

Reflects “newco” after planned adjustments such as:

excess cash/investment distributions

divestments

discontinuations

terminations

pension elimination

other benefits

facility closings

When completed, it makes sense to “gut check” the model versus the target’s

past results and its competitors. Also, reasonableness of growth rates and

margins should be considered.

Determining Residual Value

For valuations using a DCF approach, the determination of residual value is

a critical element – often the most critical – of the calculation. Frequently,

the residual component of the valuation outweighs the scheduled cash flows

component and hence significantly impacts total valuation.

The two primary approaches to residual value are:

1. Multiple of Earnings Method

2. Growing Perpetuity Method

The Multiple of Earning Method typically involves some level of earnings

(i.e. net, operating, EBITDA, EBITA et al.) or occasionally factors such as

sales or book value expressed as a multiple for valuation purposes. LBO

firms typically use an EBITDA or EBITA approach while public companies

may use a multiple of net or operating income. The characteristics of the

business and its industry may influence the choice of earnings or other factor

to be multiplied. The selection of the multiple may reflect current or

anticipated conditions at the end of specifically forecasted cash flows. In

some cases it may simply be the multiple paid for the assets or business.

The Growing Perpetuity approach assumes that cash flow is expected to

grow after the end of the period of specifically forecast cash flows. The cash

flow for the year following the forecast period is estimated and then

capitalized by a rate equal to the target’s Weighted Average Cost of Capital

(WACC) less the assumed perpetuity growth rate.

Calculate the WACC

The specifics for calculating the WACC can be found in financial analysis

textbooks and likely have been studied in other courses. Note that in

acquisition analysis, the proper WACC is that of the target – not the

acquirer. The objective is to discount at a rate that appropriately reflects the

risk profile of the investment not the investor; hence the need to use the

target’s WACC.

Drawing Conclusions On Valuation

Final decisions on valuation often are based on an examination (and perhaps

averaging) of several approaches. Obviously, this confirms that valuation is

more an art than a science!

Chart 9 in the Attachment shows how a broad application of valuation

techniques might be used to ensure that the approaches discussed above

eliminate alternatives that might create value especially when considering

divestments. This entity wants to maximize value in total by evaluating each

of its 5 business groups. Note that this thorough approach includes creating a

DCF to capture specific synergies estimated for a specific buyer as well as a

liquidation analysis, among others.

Before locking-in a valuation, an acquirer will need to understand the impact

of an offer on the accretion or dilution of earnings per share (EPS).

For most corporate senior managements and boards, projections of post

acquisition EPS dilution and accretion are of critical concern and affect their

price negotiating parameters when issuing stock. Many will tolerate limited

dilution of perhaps a few years if there is a clear long-term payout.

EPS dilution occurs whenever the P/E ratio paid for the target exceeds the

acquirer’s P/E ratio. Significantly, the magnitude and extent of continued

dilution/accretion are determined by the relative size of the earnings of the

acquirer and the target and by their relative growth rates.

A proposed acquisition valuation that meets or exceeds IRR hurdles may

well be reduced if dilution is indicated. Conversely, an expected accretive

transaction can result in raising an offer to a point where the IRR hurdle is

not met.

The simplified presentation “Stock Or Cash -- A Financial Perspective”

discussed in class and found in the attachments demonstrates how the

expectation of dilution or accretion can be a critical factor in deal structuring

as well.