[edit]Asian theatre

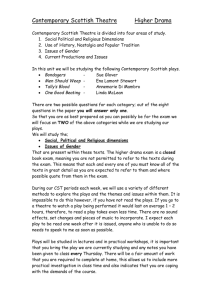

advertisement

![[edit]Asian theatre](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/008520391_1-4a10558ccfb347d40b0694e781c8992d-768x994.png)