Constructing an effective dispute settlement system: relevant

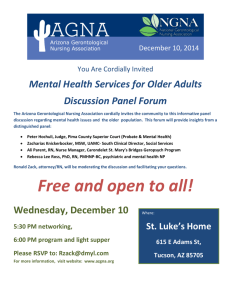

advertisement