Exploring the Relationship between Decision and Ownership Rights

advertisement

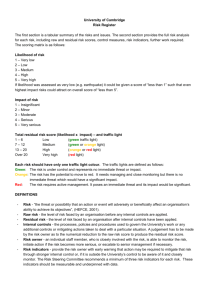

Exploring the Relationship Between Decision and Ownership Rights in Joint Ventures Evidence from Hungarian Joint Ventures Josef Windsperger A1, Eva Kocsis A2, Miklos Rosta A3 A1 Center of Business Study, University of Vienna, Bruenner Str. 72, A-1210 Vienna, Austria A2 Corvinus University of Budapest A3 Corvinus University, Fövám tér 8, H-1093 Budapest, Hungary International Studies of Management and Organization Issue: Volume 39, Number 4 / Winter 2009-10 Pages: 43 - 59 1 Exploring the Relationship between Decision and Ownership Rights in Joint Ventures: Evidence from Hungarian Joint Ventures Abstract By applying property rights theory, we argue that the structure of residual decision and ownership rights in joint ventures depends on the distribution of intangible knowledge assets between the joint venture partners. Our analysis derives the following hypotheses: The more important the joint venture partner's knowledge assets for the generation of residual surplus, the more residual decision rights are assigned to her. In addition, we examine two views on the relationship between residual decision and ownership rights in joint ventures: Under the complementarity view, ownership rights increase the knowledge and incentive effect of residual decision rights. Under the substitutability view, residual decision and ownership rights are negatively related because a certain level of control may result either from the allocation of ownership rights or the transfer of residual decision rights to the joint venture partners. These property rights hypotheses are tested in the Hungarian market. Our data confirm the hypotheses that (a) the joint venture partner’s intangible assets positively influence her proportion of residual decision rights, and (b) residual decision rights are positively related with ownership rights. Introduction Starting from Barzel, Grossman, Hart and Moore (Barzel 1997; Grossman, Hart 1986; Hart, Moore 1990), the allocation of residual decision and ownership rights depends on the distribution of intangible (noncontractible) knowledge assets that generate the firm’s residual surplus (see also Baker et al. 2004; Windsperger, Yurdakul 2007). Intangible knowledge assets refer to the knowledge and skills (know-how) that cannot be easily codified and transferred to other agents, since they have an important tacit component (Kogut, Zander 1993; Zander, Kogut 1995). In joint ventures intangible knowledge assets refer to the joint venture partners’ noncontractible capabilities (know how in R&D, production and procurement management, marketing and advertising, human resource management, organization design, strategy formation) that cannot be easily transferred by contract (Hennart 1988; Nakamura, Xie 1998). 2 The thesis of the paper is: The more important the JV-partner‘s intangible knowledge assets relative to the other for the generation of residual income, the more residual decision rights should be assigned to her. In addition, we examine two views on the relationship between residual decision and ownership rights in joint ventures: Under the substitutability view (Lecraw 1984), residual decision and ownership rights may be negatively related because a certain level of control may result either from the allocation of ownership rights or the transfer of residual decision rights to the joint venture partners. Under the complementarity view (Milgrom, Roberts 1990, 1995; Brickley et al. 1995), residual decision and ownership rights are positively related because the JV-partner’s motivation to use her knowledge assets to generate residual income is increased if ownership rights are co-located with residual decision rights. These property rights hypotheses are tested in the Hungarian market. Although many theoretical and empirical studies dealing with the allocation of residual decision rights exist in the organizational economics (Aghion, Tirole 1997; Christie et al. 2003; Baiman, Larcker, Rajan 1995; Nagar 2002; Arrunada et al. 2001; Lerner, Merger 1998; Brickley et al. 2003; Kaplan, Stromberg 2003; Elfenbein, Lerner 2003; Hendrikse 2005; Vázquez 2005), no prior research tests a property rights approach applied to joint ventures. This deficit may result from the difficulty in collecting data on intangible knowledge assets and decision rights in joint ventures. In addition, several studies in the international management literature investigate the problem of control in joint ventures (Killing 1983; Schaan 1988; Geringer, Hebert 1989; Mjoen, Tallmann 1997; Chalos, O’Connor 1998; Calantone, Zhao 2000; Pangarka, Klein 2004; Choi, Beamish 2004). However, in this literature control is a very heterogeneous concept that is only partly related to decision rights. It has been modelled by relative degree of ownership and/or a high level of management control 3 and/or a high level of control of specific activities (Blodgetts 1991a, 1991b; Gray, Yann 1992; Mjoen, Tallman 1997;Yan, Gray 2001). Starting from this deficit, we operationalize residual decision rights as control over the use of assets in a joint venture (Hansmann 1996; Nagar 2002; Elfenbein, Lerner 2003; Windsperger 2004). This view is also closely related to Rajan and Zingales’ concept of access to critical resources (Rajan, Zingales 1998; 2001). They argue power stems from control over critical assets that generate the residual income stream. Our main contribution to the joint venture literature is the following: First, we present a property rights view on the allocation of residual decision and ownership rights in joint ventures, and second we empirically investigate the structure of decision and ownership rights in Hungarian joint ventures. The paper is organized as follows. Section two uses the property rights approach to examine the relationship between the characteristics of the joint venture partner’s knowledge assets and the allocation of residual decision rights. Section three investigates the relationship between residual decision and ownership rights in joint ventures. In section four we apply this framework to derive testable hypotheses. The hypotheses are finally tested in Hungary. The Structure of Residual Decision Rights in Joint Ventures According to the property rights view, the allocation of residual decision rights depends on the distribution of intangible (noncontractible) assets: The more important a person’s intangible knowledge assets for the generation of the residual income relative to another person, the more residual decision rights should be assigned to that person. Which knowledge assets are generated and used in joint ventures? We analyse 4 a joint venture (JV) with two joint venture partners (P1, P2). The JV-partners that create a joint venture company face the problem of maximizing the returns to intangible knowledge assets of the JV-company when they are dependent on both partners’ investments in these assets. For instance, in international business relations the intangible knowledge assets (know-how) of P1 includes knowledge and skills (organizational capabilities) in product development, procurement, production and branding, and the intangible knowledge assets of P2 refer to the local market access, cultural and institutional know-how and human resource capabilities (Lecraw 1984; Fagre, Wells 1982; Hennart 1988; Nakamura 2005). How does the distribution of intangible knowledge assets between the JVpartners influence the distribution of residual decision rights in joint ventures? Residual decision rights refer to the strategic and operational decisions of the JV, such as strategy formation, organization design, product, price, marketing, advertising, procurement and production, finance and investment, human resource management, and controlling system, that generate the residual income stream. According to Jensen and Meckling (1992), two ways for allocating decision rights exist: Either knowledge must be transferred to those with the right to make decisions or decision rights must be transferred to those who have the knowledge. Thus, decision rights are allocated to P1 when the costs of transferring knowledge from P2 to P1 are relatively low. This is the case when P2‘s knowledge assets are less intangible and, therefore, more contractible. In this case, P1 has a stronger bargaining power, due to her intangible knowledge assets that generate the residual surplus, and P1 can easily acquire the knowledge assets from P2, due to its high degree of contractibility (low degree of intangibility). On the other hand, residual decision rights have to be transferred to P2 when her knowledge is very specific and consequently the knowledge transfer and 5 control costs are very high. In this case, the bargaining power of P2 is relatively strong due to her noncontractible know-how. Furthermore, if it is important to take advantage of both partners’ intangible knowledge assets to generate a high residual income stream of the JV, residual decision rights must be allocated to both partners to efficiently utilize their specific knowledge. Therefore, an efficient decision structure implies co-location of knowledge assets and decision rights (Brickley et. al. 1995). As a result, the property rights view on the allocation of decision rights in joint ventures can be summarized by the following hypothesis: H1: The higher the intangible knowledge assets of partner 1 relative to partner 2, the higher partner 1’s fraction of residual decision rights. The following example illustrates this view. We compare two situations (see figure 1): (A) P1 has a large fraction of intangible knowledge assets (for instance, technological and brand name know-how) and the know-how of P2 (for instance, local market knowledge and human resource capabilities) is less intangible and hence more contractible. Due to P1’s dominant know-how position she should get a large fraction of residual decision rights to maximize the JV’s residual income stream. (B) P2 has a large fraction of intangible knowledge assets (for instance, local market knowledge and cultural know-how) that generate a high residual surplus and the P1’s assets are less intangible. In this case, the residual decision rights must be assigned according to P1 and P2’s know-how position. Therefore, compared to case A, P2 has a stronger bargaining power and hence more residual decision rights are transferred to P2. 6 Insert figure 1 If these conditions are not fulfilled, the following inefficiencies may arise: (a) Inefficiencies arise because a large fraction of residual decision rights is transferred to P2 although P1 has the most important part of intangible knowledge assets that generates a large fraction of the total residual income stream of the JV (see (2) in figure 1); (b) inefficiencies arise because a low fraction of residual decision rights is transferred to P2, although P2 has a large part of intangible knowledge assets (see (3) in figure 1). In this case, P1 mainly influences the JV-decisions, although he has not the most relevant knowledge assets that generate the residual income stream. Consequently, if there is a misfit between the distribution of intangible knowledge assets and the allocation of decision rights the JV’s residual surplus cannot be maximized. Residual Decision and Ownership Rights: Complements versus Substitutes Since the governance structure of the JV consists of ownership and residual decision rights, the question to ask is which relation exists between ownership rights and residual decision rights. There are two views on the relationship between residual decision rights and ownership rights: (I) Complementarity view: This view was developed by Milgrom and Roberts (1990; 1995). Milgrom and Roberts’ supermodularity theory predicts that investments in one organizational practice (e.g. information technology) will generate increased residual income of the firm only if they are bundled with investments in other organization design variables, such as more decentralized decision-making, more highly skilled workers and more performance-based incentives (see also Arora, 7 Gambardella 1990; Brickley et al. 1995). Thus, a joint implementation of several organizational practices may lead to economies of scope (Baumol et al.1988). Applied to the governance structure of joint ventures, complementarity means that the transfer of ownership rights increases the residual income-increasing effect of the transfer of decision rights, and the transfer of decision rights increases the residual incomeincreasing effect of ownership rights (Van den Steen 2006). Therefore, residual decision and ownership rights are positively related. (II) Under the substitutability view, residual decision and ownership rights are negatively related. In this case, the transfer of ownership rights decreases the residual income-increasing effect of the transfer of decision rights, and the transfer of decision rights decreases the residual income-increasing effect of ownership rights (Lokshin et al. 2004). As Lecraw (1984) has already argued, residual decision and ownership rights in joint ventures may be negatively related because a certain level of control may result either from the allocation of ownership rights (as formal authority) or the transfer of residual decision rights (as real authority) (Aghion, Tirole 1997). Under this view, the more residual decision rights are assigned to a joint venture partner, the less ownership rights must be transferred to her to maintain a certain level of control over the firm’s intangible assets. Hence, a lower proportion of ownership rights must be compensated by a higher proportion of residual decision rights. We can derive the following hypotheses: H2a: Complementarity view: The JV-partner’s residual decision rights are positively related with the proportion of ownership rights. H2b: Substitutability view: The JV-partner’s residual decision rights are negatively related with the proportion of ownership rights. 8 Empirical Analyses Data Collection and Measurement The empirical setting for testing these hypotheses is the Hungarian market. We used a questionnaire to collect the data from a sample of 530 Hungarian companies. The data set was collected between October 2004 and March 2005. The questionnaire took approximately 15 minutes to complete. We received 80 completed responses. To trace non-response bias, we investigated whether the results obtained from analysis are driven by differences between the group of respondents and the group of nonrespondents. Non-response bias was measured by comparing two groups of responders (October 2004, March 2005) (Amstrong & Overton 1977). No significant differences emerged between the two groups of respondents. To test our property rights hypotheses, the following variables are included in the regression analysis: Intangible knowledge assets, ownership rights, residual decision rights, as well as firm size, age and technological uncertainty as control variables (see appendix). Intangible Knowledge Assets (KNOW): The joint venture partner’s intangible assets refer to the specific knowledge of local markets, distribution channel, procurement, human resource management, technological know how, organizational capabilities, and knowledge of cultural and the institutional environment. In the questionnaire, the general managers of the Hungarian JV-companies were asked to rate on a seven-point scale the JV-partner's intangible assets. A ten-item scale measures the relative knowhow advantage of partner 1 compared to partner 2 (partner 1 is the partner with the higher equity stake). The ten-item measure was extracted by employing factor analysis. All variables had a loading in excess of 0.7. The total amount of variance 9 explained by the factor solution is 64 percent. The reliability of this scale was assessed by Cronbach’s alpha (0.93). Residual Decision Rights (DR): The indicator of decision rights (DR) is a measure about the distribution of decision-making authority between the joint venture partners. Our decision rights variable includes the following decisions of the JV: Procurement decision, price and product decisions, advertising decision, human resource decisions (recruitment and training), investment and finance decisions, strategy formation and organization decisions, and decisions concerning the application of accounting and control systems. The indicator of decision rights addresses the extent to which residual decisions are influenced by partner 1 compared to partner 2. Hence, it is a measure for distribution of the decision-making power in the joint venture company that is compatible with Nagar’s measure of decision rights in retail banking (Nagar 2002) and Windsperger’s measure of decision rights in franchising networks (2004). The general managers of the joint venture companies were asked to rate the joint venture partner's influence on these decisions on a seven-point scale. Ownership Rights (OR): The joint venture partner’s ownership rights (OR) are measured by the percentage of ownership of the joint venture partners in the joint venture company (= equity ratio). Control Variables We controlled for three variables that might affect the allocation of decision rights in joint ventures. Firm Size (SIZE): We use the sale value of the JV-partner’s parent firm as proxy of the firm size representing economies of scale of coordination and monitoring (Brickley et al. 1991). The larger the size of the parent firm, the larger its 10 coordination and monitoring capacity, the more easily the parent firm can control the joint venture company, and hence the lower the propensity to transfer residual decision rights to the other partner. Joint Venture Experience (AGE): We use the number of years of the joint venture company’s existence as proxy for interorganizational learning. The older the joint venture company, the larger the knowledge conversion effect from tacit (noncontractible) to more explicit (contractible) knowledge due to interorganizational learning (Inkpen 2000; Nonaka, Takeuchi 1995), and the more control can be exercised. Technological Uncertainty (UNCERT): We use technological uncertainty as proxy for knowledge spillover costs. Knowledge spillover costs may arise because the joint venture partner has access to intangible knowledge of the other partner(s) after the joint venture company was created (Inkpen 2000; Nakamura 2005; Hennart, Zeng 2005). Under given intangible knowledge assets, the spillover costs may increase with technological uncertainty. The higher the technological uncertainty, the higher the knowledge spillover risk, and the more residual decision rights are required to capture a large fraction of the residual surplus. Results Table 1 and 2 contain descriptive data of the Hungarian joint venture companies. Insert Table 1 and 2 11 H1: Decision Rights-Hypothesis To test this hypothesis (H1) we carry out an ordinal regression analysis with the index of decision rights (DR) as dependent variable (Chu, Anderson 1992): The explanatory variables refer to joint venture partner’s knowledge advantage (KNOW), firm size (SIZE), age (AGE), and technological uncertainty (UNCERT). We estimate the following regression equation: DR = + 1KNOW+ 2SIZE + 3AGE + 4UNCERT Based on our property rights hypothesis, decision rights (DR) positively vary with the P1’s know-how advantage (KNOW). Further, we include three control variables: DR positively vary with SIZE due to economics of scale of coordination and monitoring, AGE due to organizational learning, and technological uncertainty (UNCERT) due to the knowledge spillover risk. Hence 1, 2, 3 and 4 have a positive sign. The results of the ordinal regressions are provided in table 3. The fit of the models was based on the log of the likelihood ratio. The chi-square value of 31.178 is significant at p < 0.001 thus rejecting the null hypothesis that the estimated coefficients are zero. The overall fit of the ordinal regression model point to the appropriateness of the set of variables in predicting the distribution of residual decision rights in joint ventures. The coefficient of intangible knowledge assets (KNOW) is highly significant and consistent with our property rights hypothesis. The larger the know-how advantage, the more residual decision rights are transferred to P1. In addition, the coefficients of SIZE and UNCERT have the expected positive sign and are significant. On the other hand, AGE is not significant. Finally, colinearity 12 diagnosis was performed using correlations between the independent variables (see table 4). Insert Table 3 and Table 4 H2: Interaction between Decision and Ownership Rights Several studies (Arora & Gambaredella 1990; Ichniowski et al. 1997; Laursen & Mankhe 2001; Hitt & Brynjolffson 1997) empirically measured interactions between organizational variables. We test the interaction effects between residual decision rights (DR) and ownership rights (OR) - hypotheses (H2a, H2b) – by using partial correlations. Following Arora & Gambardella 1990 and Arora 1996, we apply the correlation analysis for examining possible complementarities/ substitutabilities between residual decision rights and ownership rights in joint ventures. Since a simple correlation might be spurious, because a common set of factors influences the governance structure variables, we compute conditional correlations between the decision and ownership rights variables (Hitt & Brynjolffson 1997). Therefore, correlation analysis is done, controlling for the knowledge assets, technological uncertainty and size. The correlation coefficient between the JV-partner’s proportion of ownership rights and the decision index is positive and highly significant (0.411; p < 0.01). This result suggests that residual decision and ownership rights are complements in joint ventures. In addition, ordinal regression analysis also confirms this result (see table 5. The coefficient of the proportion of ownership (OR) is positive and highly significant. Insert Table 5 13 Discussion and Implications The goal of the paper is to provide a property rights view on the allocation of residual decision and ownership rights in joint ventures. First, we test the hypothesis that the joint venture partner’s residual decision rights directly vary with the importance of her intangible knowledge assets to generate the ex post surplus of the joint venture. The data from 80 Hungarian joint ventures confirm the hypothesis that the joint venture partner’s intangible assets positively influence the tendency toward a higher proportion of residual decision rights. Second, we investigate the relationship between residual decision and ownership rights of the joint venture partners. Our results are compatible with the complementarity view of governance structure (Milgrom, Roberts 1995; Jensen, Meckling 1992; Roberts 2004). The JV-partner’s motivation to use her intangible knowledge assets to generate residual income is increased if ownership rights are co-located with residual decision rights. The data from 80 Hungarian joint ventures support this hypothesis. Compared to previous research, our study made an important contribution to operationalize the residual decision rights of the joint venture partners. Consistent with Yan and Gray’s view (Yan, Gray 2001), we developed a measure for residual decision rights consisting of strategic and operational decisions. However, our empirical study has some limitations: First, although the database in the survey sample is diverse, it remains far from a large and statistically random sample. Second, while the empirical results provide support for the property rights hypotheses, additional empirical evidence is required to increase the generalizability of the results. Furthermore, future research has to investigate the relationship between allocation of decision and ownership rights and the performance of the joint venture. Our property 14 rights proposition suggests a positive relationship between complementarity of decision and ownership rights, on the one hand, and performance of the joint venture company, on the other hand. This study also has managerial implications. First, the result of this study indicates that the allocation of decision rights in joint ventures must be based on the distribution of the JV-partners intangible knowledge assets for the creation of residual surplus. Therefore, this study provides companies with guidance to structure residual decision rights in joint ventures. High noncontractible know how may generate high residual surplus for the joint venture company, if the joint venture partner has the relevant residual decision rights to efficiently use her intangible knowledge assets for the creation of the total income stream. Conversely, low intangible and hence contractible know how does not influence the residual income stream of the joint venture even if the joint venture partner has a high proportion of residual decision rights. Second, our results suggest that the use and creation of knowledge in joint ventures can be improved, if residual decision rights are co-located with ownership rights. This is especially important in the case of joint ventures for the creation of innovations (Grandori, Furlotti 2006). For instance, high innovation capabilities of a joint partner with a high fraction of residual decision and ownership rights are likely to generate a high residual surplus because the partner is motivated to efficiently use her intangible innovation assets. On the other hand, high innovation capabililties of a partner with a low fraction of residual decision rights are unlikely to maximize the residual income stream because the joint parnter is unable to influence the use of innovation assets, even if she has a large fraction of ownership rights. Moreover, high innovation capabilities of a partner with a high fraction of decision rights but a low fraction of ownership rights are also unlikely to generate a high residual surplus 15 because the partner has not the incentive to efficiently use her innovation assets under a small proportion of ownership rights. 16 References Aghion, Philippe, and Jean Tirole 1997. Formal and Real Authority in Organization. Journal of Political Economy, 105, 1 – 29. Armstrong, J. Scott, and Terry S. Overton 1977. Estimating Non-Response Bias in Mail Surveys, Journal of Marketing Research, 14, 396 – 402. Arora, Ashish, Gambardella Alfonso 1990. Complementarities and External Linkages: The Strategies of the Large Firms in Biotechnology. Journal of Industrial Economics, 38, 361 – 379. Arora, Ashish 1996. Testing for Complementarities in Reduced-form Regressions: A Note. Economics Letters, 50, 51 – 55. Arrunada, Benito, Luis Garicano, Luis Vazquez 2001. Contractual Allocation of Decision Rights and Incentives: The Case of Automobile Distribution. Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, 17, 256 – 283. Baiman, Stanley, David F. Larcker, Madhav V. Rajan 1995. Organizational Design for Business Units. Journal of Accounting Research, 33, 205 – 229. Baker George P., R. Gibbons, K. J. Murphy 2004. Strategic Alliances: Bridges between “Islands of Concious Power”. Working Paper, Harvard Business School. Barzel, Yoram 1997. Economic Analysis of Property Rights, New York. Baumol, W., J.C. Panzar, R.D. Willig 1988. Contestable Markets and the Theory of Industry Structure, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. Blodgett, Linda L. 1991a. Towards a Resource-Based Theory of Bargaining Power in International Joint Ventures. Journal of Global Marketing, 5, 35 – 54. Blodgett, Linda L. 1991b. Partner Contributions as Predictors of Equity Share in International Joint Ventures. Journal of International Business Studies, 22, 73 – 78. Brickley, James, Frederick Dark, Michael Weisbach 1991. An Agency Perspective on Franchising. Financial Management, 20, 27 – 35. Brickley, James A., Clifford W. Smith, Jerold L. Zimmerman 1995. The Economics of Organizational Architecture. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 8, 19 – 31. Brickley, James A., Clifford W. Smith, James S. Linck 2003. Boundaries of the Firm: Evidence form the Banking Industry. Journal of Financial Economics, 70, 351 – 376. Calatone, Roger J., Yushan Sam Zhao 2000. Joint Ventures in China: A Comparative Study of Japanese, Korean, and U.S. Partners. Journal of International Marketing, 10, 53 – 77. Chalos, Peter, Neale G. O’Connor 1998. Management Control in Sino-American Joint Ventures: A Comparative Case Analysis. Managerial Finance, 24, 53 – 72. Choi, Chung-Bum., Paul W. Beamish 2004. Split Management Control and International Joint Venture Performance. Journal of International Business Studies, 35, 201 – 215. Christie, A., A., M. P.Joye, R.L.Watts 2003. Decentralization of the Firm: Theory and Evidence. Journal of Corporate Finance, 9, 2 – 36. Chu, Wujin, Erin M.Anderson 1992. Capturing Ordinal Properties of Categorical Dependent Variables:A Review with Application to Modes of Foreign Entry. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 9, 149 – 160. Elfenbein, Dan, Josh Lerner 2003. Ownership and Control Righs in Internet Portal Alliances, 1995 – 1999. RAND Journal of Economics, 34, 356 – 369. Fagre, Nathan, Louis T. Wells 1982. Bargaining Power of Multinationals and Host Governments. Journal of International Business Studies, Fall, 9 -23. 17 Geringer, J. Michael, Louis Hebert 1989. Control and Performance of International Joint Ventures. Journal of International Business Studies, Summer, 235 – 254. Grandori, Anna, Marco Furlotti 2006. The Bearable Lightness of Inter-firm Strategic Alliances: Resource-based and Procedural Contracting, in Arino, A., J. Reuer (eds.), Strategic Alliances: Governance and Contracts. London. Gray, Barbara, Aimin Yan 1992. A Negotiation Model of Joint Venture Formation, Structure and Performance: Implications for Global Management. Advances in International Comparative Management, 7, 41 – 75. Grossman, Stanley J., Oliver D. Hart 1986. The Costs and Benefits of Ownership: A Theory of Vertical and Lateral Integration. Journal of Political Economy, 94, 691 – 719. Hansmann, Henry 1996. The Ownership of the Enterprise, Cambridge, MA. Hart, Oliver, John Moore 1990. Property Rights and the Nature of the Firm. Journal of Political Economy, 98, 1119 – 1158. Hendrikse, G. W. J. 2005. Contigent Control Rights in Agricultural Cooperatives, in T. Theurl, E. C. Meijer (eds.), Strategies for Cooperation. Aachen, 385 – 394. Hennart, Jean-Francois 1988. A Transaction Cost Theory of Equity Joint Ventures. Strategic Management Journal, 9, 361 – 374. Hennart, Jean-Francois, Ming Zeng 2005. Structural Determinants of Joint Venture Performance. European Management Review, 2, 105 – 115. Hitt, Lorin M., Erik Brynjolfsson 1997. Information Technology and Internal Firm Organization: An Exploratory Analysis. Journal of Management Information Systems, 14, 81 – 101. Ichniowski, C., K. Shaw, G. Prennushi 1997. The Effects of Human Resource Management Practices on Productivity. American Economic Review, 87, 291 – 313. Inkpen, Andrew C. 2000. Learning Through Joint Ventures: A Framework of Knowledge Acquisition. Journal of Management Studies, 37, 1019 – 1043. Jensen, Michael C., William H. Meckling 1992. Specific and General Knowledge and Organizational Structure, in: L. Werin, H. Wijkander (eds.), Contract Economics. Oxford, 251 – 274. Kaplan, Steven N., Per Stromberg 2003. Financial Contracting Theory Meets the Real World: Evidence from Venture Capital Contracts. Review of Economic Studies, April, 281 – 316. Killing, J. Peter 1983. Strategies for Joint Venture Success, New York. Kogut, Bruce, Udo Zander 1993. Knowledge of the Firm and the Evolutionary Theory of the Multinational Corporation. Journal of International Business Studies, 24, 625 – 645. Laursen, Keld, Volker Mahnke 2001. Knowledge Strategies, Firm Types, and Complementarity in Human-Resource Practices. Journal of Management and Governance, 5, 1 – 27. Lecraw, Donald J. 1984. Bargaining Power, Ownership, and Profitability of Transnational Corportations in Developing Countries. Journal of International Business Studies, Summer, 27 – 43. Lerner, Josh, Robert P. Merges 1998. The Control of Strategic Alliances: An Empirical Analysis of Biotechnology Collaborations. Journal of Industrial Economics, 46, 125 – 156. 18 Lokshin, Boris, René Belderbos, Martin Carree 2004. Testing for Complementarity and Substitutability in Case of Multiple Practices. METEOR memorandum RM04002, University of Maastricht. Milgrom, Paul, John Roberts 1990. The Economics of Modern Manufacturing: Technology, Strategy, and Organization. American Economic Review, 80, 511 – 28. Milgrom, Paul, John Roberts 1995. Complementarities and Fit: Strategy, Structure and Organizational Change in Manufacturing. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 19, 179– 208. Mjoen, Hans, Stephan Tallmann 1997. Control and Performance in International Joint Ventures. Organization Science, 8, 257 – 274. Nagar, Venky 2002. Delegation and Incentive Compentsation. Accounting Review, 77, 379 – 395. Nakamura, Masao, J. Xie 1998. Nonverifiability, Noncontractibility and Ownership Determination Models in Foreign Direct Investment. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 16, 571 – 599. Nakamura, Masao 2005. Joint Venture Instability, Learning and the Relative Bargaining Power of Parent Firms. International Business Review, 14, 465 – 493. Nonaka, I., H. Takeuchi 1995. The Knowledge Creating Company, New York. Pangarkar, Nitin, Saul Klein 2004. The Impact of Control on International Joint Venture Performance: A Contingency Approach. Journal of International Marketing, 12, 86 – 107. Rajan, Raghuram, Luigi Zingales 1998). Power in a Theory of the Firm. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 108, 387 – 432. Rajan, Raghuram, Luigi Zingales 2001. The Firm as Dedicated Hierarchy: A Theory of the Origins and Growth of Firms. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116, 805 - 852. Roberts, J. 2004. The Modern Firm: Organizational Design for Performance and Growth, Oxford. Schaan, Jean-Louis 1988. How to Control a Joint Venture Even as a Minority Partner. Journal of General Management, 14, 1988, 4 – 16. Van den Steen, Eric 2006. Disagreement and Allocation of Control. MIT Sloan Working Paper 4610-06, June 2006. Vazquez, Xosé H. 2005. Allocating Decision Rights on the Shop Floor: A Perspective from Transaction Cost Economics and Organization Theory. Organization Science, 15, 463- 480. Windsperger, Josef 2004. Centralization of Franchising Networks: Evidence from the Austrian Franchise Sector. Journal of Business Research, 57, 1361 – 69. Windsperger, Josef, Askin Yurdakul 2007. The Governance Structure of Franchising Firms: A Property Rights View, in: Gérard Cliquet et al. (eds.), Economics and Management of Networks: Franchising, Strategic Alliances, and Cooperatives, Heidelberg. Yan, Aimin, Barbara Gray 2001. Antecedents and Effects of Parent Control in International Joint Ventures. Journal of Management Studies, 38, 393 – 416. Zander, Udo, Bruce Kogut 1995. Knowledge and the Speed of the Transfer and Imitation of Organizational Capabilities: An Empirical Test. Organization Science, 6, 76 – 92. 19 APPENDIX: MEASURES OF VARIABLES Intangible knowledge assets (KNOW) (1 – 7) (ten items; Cronbach Alpha = 0.93): JV-partner 1’s relative know-how advantage compared to JV-partner 2 concerning the following value chain activities: (Production and logistics, recruiting, local market services, strategic planning, controlling, R&D, organization design, strategy formation, local market knowledge, local institutional knowledge) Firm size (SIZE): Average sale value of the parent firm of JV-partner 1 (per year) Technological uncertainty (UNCERT) (1 – 5): The JV-manager has to evaluate technological uncertainty on a 5-point scale: Extent of technological changes. Decision rights index (DR) (Mean): To which extent does JV-partner 1 influence the following decisions compared to JV-partner 2? (1 – 7) (Recruiting, training, selection of cooperation partners, selection of suppliers, incentives and wages, promotion and advertising, investment projects, price decisions, organization structure and strategy, marketing, product management, production and procurement, accounting and controlling system, selection of lenders) Age of the JV-company (AGE): Number of years of existence Ownership rights (OR): Percentage of asset ownership of joint venture partner 1 (= equity ratio) 20