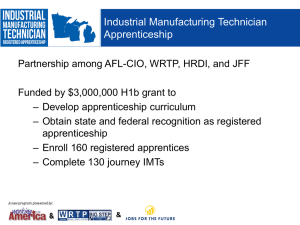

Accelerated apprenticeships

advertisement