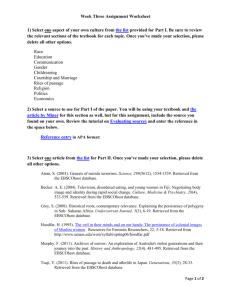

Week One Readings - University of Phoenix

advertisement