CVC: current trends and future directions ABSTRACT Corporate

advertisement

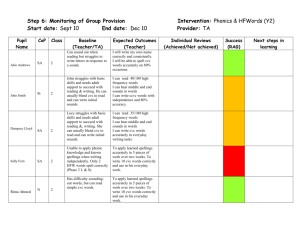

CVC: current trends and future directions ABSTRACT Corporate Venture Capital (CVC) investments consist of minority equity stakes in relatively new, not publicly traded companies that are seeking capital to continue operation. Corporate Venture Capital (CVC) has been recognized as important vehicle for fostering entrepreneurial development. Although there exists already an amount of theoretical as well as empirical studies aiming at explaining, predicting or understanding CVC activity in firms growth, there seems to be a growing dissatisfaction among scholars with the fragmented findings that have emerged to date. In fact CVC activities play an increasingly important role in value creation for both start-ups and the large companies that invest in them, but it remains unclear how both corporate venturers and start-up recipients capture and measure the strategic value of corporate venture capital investments. The current paper intends to present a review of the existing literature. Results present a fragmented literature with a proliferation of different perspectives. Keywords: CVC, entrepreneurial development, organizational performance INTRODUCTION Scholars have long been interested in the components and forms of the ‘knowledge production function’—the process by which innovative inputs are transformed into innovative outputs (Dushnitsky and Lenox, 2005). In the past, the innovation literature has mainly focused on the role of internal R&D on firm innovation (Griliches, 1979), even though internal R&D expenditures play only a limited role in firm innovation rates. Actually, companies pursue innovation mainly by investing in external entrepreneurial ventures. This phenomenon is generally referred to as Corporate Venture Capital (also known as CVC). It represents an equity investment by large corporations in entrepreneurial ventures that originate outside the corporation (Roberts and Berry, 1985). CVC activities have been playing an increasingly important role in innovation strategy for large corporations across the globe. Figures about recent trends within the venture capital industry point to that, after a period of decline at the end of the dotcom boom between 2000 and 2003, corporations are now responsible for a significant share of venture capital investments. By way of example, in 2009, around 20 per cent of the Fortune 500 companies created a CVC unit (Dushnitsky, 2011). It is therefore not surprising that today CVC is increasingly regarded by organizations as a vital weapon in their entrepreneurial and innovation armory. CVC has significantly evolved over time. As Chesbrough (2000: 32) contends, ‘the most recent cycle of corporate venturing has utilized venture capital structures to motivate employees to become more entrepreneurial and take more risk’. CVC programs can create value for both start-ups and the large companies that invest in them. Corporate Venture Capitalist can allow access to complementary technologies and a general window on technology developments (Fox 2003; Gompers 2002). Startups benefit from, for instance, increased access to markets and customers as well as management advice (McNally 1997; Muller et al., 2004). However, it remains unclear how both corporate venture capitalists and start-up recipients capture and measure the strategic value of corporate venture capital investments (Allen and Hevert 2007). The heterogeneity of CVC investments and the variety of motives pushing companies to pursue them makes it relevant to understand more in depth how CVC works and performs. This is the aim of the paper, to provide an assessment of the current state of the literature on CVC, and identify issues that deserve further attention. To achieve this aim we review the existing literature on CVC in an attempt to systematize current research and identify future avenues of investigation. This paper is organized as follows. In the next section we describe the method for the study. We then present findings. The paper ends with discussing what our findings mean for the community of scholars. METHOD FOR THE REVIEW To address our research question, we carry out a literature review. Our review is systematic in nature and narrative in terms of presentation of findings (see also Meglio & Risberg, 2011 for a detailed protocol for a review). Below we describe the protocol we followed in drawing our sample and classifying articles included in the sample. To identify articles for the review, we searched into EBSCO source complete database. The keyword for the search was Corporate Venture Capital. We delimited our search to the time frame2000-2012, as the number of CVC investments in high-tech industries has been growing dramatically since the beginning of 1990s. We decided to look in to top-tier management journals as well as those focused on knowledge-related topics (Linton, 2006), accounting for both American and European perspectives. We therefore focused on the following journals: Academy of Management Journal, Business Strategy Review, California Management Journal, Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, International Studies of Management and Organization, Journal of Management Studies, Journal of Small Business Management, Organization Science, R&D Management, Research Technology Management, Strategic Management Journal. We narrowed our sample by excluding those articles not explicitly addressing CVC issues. Moreover, we left out theoretical article. The final sample comprises 26 articles, each of them featuring an empirical study (Table 1). Table1. Composition of the Sample Journal Academy of Management Journal Business Strategy Review California Management Review Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice International Studies of Management Organization Journal of Management Studies Journal of Small Business Management R&D Management Research Technology Management Strategic Management Journal TOTAL and 2000-2009 2 1 2 - 2010-2012 2 1 1 3 1 2 3 3 17 3 2 9 From the table, it clearly emerges that CVC is a topic that attracts interest from different readerships, within journals with different aims and scopes. Specifically, it interests both more generalist journals, such as Academy of Management Journal, and focused ones, such as Research Technology Management. From each article, we collected information according to a reading note, organized around different sections. Besides identification information (author, outlet, year of publication), we wrote down the research questions authors investigate. In describing the CVC under analysis, we classified CVC operations in terms of aims, units of analysis, countries and time span. In the research method section, we categorized studies as quantitative, qualitative or mixed and as relying on secondary and/or primary data. In addition, we noted the theoretical frameworks employed and summarized main findings. FINDINGS Our paper focuses on CVC activity, a corporate activity particularly relevant in hightech industries. Gompers and Lerner (2000) define CVC investments like established industry incumbents’ participation in the private equity market by providing start-ups with funding in return for equity positions (Gompers and Lerner, 2000). Although all CVC investments have financial motivations (Chesbrough, 2002), learning and the gathering of market and technology intelligence are generally recognized as being among the most important objectives of this investment activity (Dushnitsky and Lenox, 2005; Wadhwa and Kotha, 2006), particularly in technology-intensive industries. Main attention in these articles are high tech firms (ICT, telecommunication, computer software, computer services), as they are active in venture capital operations aimed at developing technological expertise. As for the research focus, the elaboration of our data shows that literature proceeds from three directions – financial performance of CVC; CVC as a path to develop new technology; and CVC impact on new organization (Table 2). Table2. Research Focus in CVC Research Finance Management innovation of knowledge Allen and Hevert (2007); Benson and Ziedonis (2009); Dushnitsky and Lenox (2006); Park and Steensma (2012); Gaba and Meyer (2008) and Wadhwa and Kotha (2006); Dushnitsky and Lenox (2005); Keil (2002); Keil (2004); Schildt, Maula and Keil (2005); Keil, Autio and George (2008); Markman et al. (2008); Dushnitsky and Shaver (2009); Dushnitsky and Shapira (2010); Gaba and Meyer (2008); Souitaris et al. (2012); Dokko and Gaba (2012); Weber and Weber (2010) Strategy and organization Sykes (1990); Ernst, Witt and Brachtendorf (2005); Engel (2011); Napp and Minshall (2011); Waites and Dies (2006); Chesbrough and Socolof (2000) Looking into the geographical areas covered by empirical research, our paper shows that the number of CVC studies on countries other than the US is small but appears to be growing. Specifically, the majority of the articles are focused on US and Canada (21), with the remaining studies investigating Europe (three) and Asia (two). The acquisition of innovation and knowledge is one of the most important result of a CVC activity. Knowledge accumulation and transfer may be critical for the successful operation of the CVC. For these reasons most of the papers typically focus on the CVC programs (Table 3). Knowledge accumulates either through practice or by observing and analyzing competitors’ venturing activities. In doing so, the corporation learns how to organize its CVC program effectively, possibly promoting learning. However the literature analysis shows that a not systematic effort has been devoted to conceptualize and capture this learning. The “Parent” organization was another important unit of analysis. Studies conducted on "parent-venture relation" typically investigate specific ventures. These studies often examine the intensity of a company’s CV activities, counting the number of CV units created by a corporation. Researchers have also invoked numerous theories, discussing their theoretical preferences and the research questions pursued. An analyses into the theories used in prior studies suggests that no single, dominant theoretical approach seems to have guided past empirical analyses (Narayan et al., 2009). Table 3. Level of analysis employed in the CVC literature Relation between parent and venture Chesbrough and Socolof (2000); Chesbrough (2000); Ernst, Witt and Brachtendorf (2005); Waites and Dies (2006); Dushnitsky and Lenox (2006); Program Keil et al. 2008; Keil Weber and Weber (2010); Dushnitsky and Lenox (2005); Wadhwa and Kotha (2006); Gaba and Meyer (2008); Keil et al. (2008); Dushnitsky and Shapira (2010); Dushnitsky and Shaver (2009); Napp and Minshall (2011); Dokko and Gaba (2012); Park and Steensma (2012); Souitaris et al. (2012) In the sample of articles, a branch of studies focus attention on financial aspect of CVC activity. Allen and Hevert (2007) develop a paper on financial returns and strategic benefits of Venture Capital investments in information technology companies. They evaluate direct returns of programs of U.S. IT companies during 1990–2002 concluding that ‘Direct gains (losses) were widely dispersed and bi modally distributed, based on IRR and net cash flow metrics. Timing of initiation within the venture capital cycle; program scale; and annual investment, write-down, and harvest behavior were associated with differences in returns’ (Allen and Hevert, 2007: 262). Another important study is the one conducted by Benson and Ziedonis (2009). They build on previous studies that suggest that information gained through CVC-related activities can improve the internal R&D productivity of established firms, and investigate an alternative means by which information gained through CVC investing could improve firm performance—by increasing the returns to corporate investors when acquiring startups. They conduct an event study of the returns to 34 corporate investors from acquiring 242 technology startups. Results confirm predictions drawn from the absorptive capacity literature and point to that the effect of CVC investing on acquisition performance hinges critically on the strength of the acquirer’s internal knowledge base. ‘CVC investments increase relative to an acquirer’s total R&D expenditures, acquisition performance improves at a diminishing rate. We also find that firms consistently engaged in venture financing earn greater returns when acquiring startups than do firms with more sporadic patterns of investing, even controlling for firm profitability, size, and acquisition experience’ (Benson and Ziedonis, 2009: 329). Dushnitsky and Lenox (2006) develop a paper using a panel of CVC investments. Scholars suggest that established firms face underlying challenges when investing CVC. Namely, structural deficiencies inherent in corporate venture capital may inhibit financial gains, but they find ‘that corporate venture capital investment will create greater firm value when firms explicitly pursue corporate venture capital to harness novel technology’ (Dushnitsky and Lenox, 2006: 753). Park and Steensma (2012) address the question ‘When does Corporate Venture Capital Add Value for New Ventures?’ , and explore conditions under which CVC funding is beneficial to new ventures. They use a sample of 198 wireless communications service, 111 computer hardware, and 199 semiconductor 3111//3112) ventures founded in the United States that received their first round of funding from CVC and/or IVC funds between 1990 and 2003. They results show that CVC activities became prevalent after 1990 (Gaba and Meyer, 2008). This research shows that CVC funding presents both advantages and disadvantages for new ventures. Authors explored conditions under which CVC funding may be particularly beneficial to new ventures’ performance. They conclude that‘the tight relationship between new ventures and corporate investors is particularly beneficial in attaining specialized complementary assets. Such equity relationships can mitigate potential opportunistic behavior between new ventures and the providers of specialized complementary assets. It appears that when new ventures require specialized complementary assets, the benefits of corporate investor ties outweigh the ability to access the open market. In contrast, we found that the benefits of CVC funding to new venture performance was relatively limited for those new ventures that merely required generic complementary assets, and the benefits of an equity tie with a corporate investor were minimal is such situations’ (Park and Steensma, 2012: 17). A second branch of studies focus on management of innovation (learning and the gathering of market and technology intelligence. Wadhwa and Kotha (2006), using longitudinal data on 36 firms in the telecommunications equipment manufacturing industry during the period 1989–99, investigate the conditions under which CVC investments affect knowledge creation for corporate investors. Results indicate that there is an optimum point beyond which the contribution of CVC investments to investor knowledge creation declines. Results also suggest that when a corporate investor is highly involved with portfolio firms, it may be possible to reverse this decline. They contend that ‘greater involvement with portfolio firms has a positive effect on the inverted U-shaped relationship between corporate venture capital investment and investors’ knowledge creation. No such effect was found for investors’ technological knowledge diversity’ (Wadhwa and Kotha, 2006: 820). Dushnitsky and Lenox (2005) find that firms realize ‘corporate venture capital’ activities in industries with weak intellectual property protection and, to some extent, in industries with high technological ferment and where complementary distribution capability is important. They find that firm’s cash flow combined with absorptive capacity makes the investment e likely (Dushnitsky and Lenox, 2005). As innovative start-ups often operate in domains of emergent industry practice, CVC investment provides a valuable mechanism through which incumbents can develop cognizance of future capability needs (Keil, 2002). Keil (2004) studies the important role that initial conditions and knowledge management practices play in determining the direction and effectiveness of specific learning processes that lead to an external corporate venturing capability. He aims to answer two questions. Specifically,: ‘Through what processes do firms develop new competencies? What factors govern processes of competence development?’. In his study he develops a model that explains the learning processes through which firms develop an external corporate venturing capability. This model describes how firms develop a capability to create and develop ventures through corporate venture capital, alliances, and acquisition. In his model, external corporate venturing capability is the outcome of learning processes. Specifically, he finds out forms of learning-by-doing (Levitt and March, 1988) and experiential learning (Huber, 1991) as well. However, the organization also learns outside such external corporate venturing relationships by relying, for instance, on new employees or consultants (Keil, 2004). In addition, Schildt, Maula and Keil (2005) compare different forms of external corporate venturing, namely corporate venture capital investments, alliances, joint ventures, and acquisitions, as alternative means for inter-organizational learning. They examine the antecedents of explorative and exploitative learning of technological knowledge from external corporate ventures. Their empirical analysis is based on 110 largest public U.S. corporations operating in four sectors of ICT industries. They find that technological relatedness and downstream vertical relatedness together decrease the likelihood of explorative learning. This implies that companies aimed at enhancing their explorative learning need to seek partners with dissimilar technologies and beyond their customers. Contrary to their expectations, empirical results do not support any kind of relationship between industry relatedness and explorative learning (Schildt, Maula and Keil, 2005). Keil, Autio and George (2008) examine how firms engender cognizance of their future capability needs in situations characterized by high decision-making uncertainty. They develop a theoretical account of how firms use investments in start-ups to actively engage in experimentation outside organizational boundaries, a learning process which we term as disembodied experimentation. Disembodied experimentation, they argue, is a form of experimental learning whose aim is to understand action-outcome relationships (Keil, Autio and George, 2008). They find two factors influencing the relationship between disembodied experimentation and capability building decisions: a knowledge-brokering role or strategy seems to be a critical positive moderator of the likelihood of internalization,… Second, simultaneous changes in technology and business models determine adaptation complexity that reduces the likelihood of disembodied experimentation affecting capability building decisions (Keil, Autio and George, 2008). Another branch of studies analyze aspect linked on strategy and organization. Keil and colleagues (2008) examine how different governance modes for external business development activities and venture relatedness affect a firm’s innovative performance. Based on idea that interorganizational relationships enhance the innovative performance of firm, they analyze a panel of the largest firms in four ICT sectors. Results extend past studies by examining how the relationship between various external business development activities and innovative performance depends on venture relatedness. Specifically, their study shows that alliances, joint ventures, and CVC investments in related industries have a significantly positive correlation with innovative performance>> (Keil et al., 2008). Markman et al. (2008) analyze organizational interactions involving universities and firms that result in the commercialization of research and technology. They develop a taxonomy of modes of commercialization that builds on internal approaches, quasiinternal approaches (e.g. incubators), university research parks, regional clusters, academic spin-offs and start-ups, licensing, contract research and consultancy, corporate venture capital, and open science and innovation (Markman et al., 2008). Dushnitsky and Shaver (2009) analyze limitations to interorganizational knowledge acquisition. They study a panel of 1,646 start-up-stage ventures that received funding during the 1990s. they find that under a regime of weak intellectual property protection (IPP), an entrepreneur-CVC investment relationship is less likely to form when the entrepreneurial invention targets the same industry as corporate products. In contrast, under a strong IPP regime, industry overlap is associated with an increase in the likelihood of an investment relationship. For these reason they conclude that ‘CVC has a greater capability and inclination to target an entrepreneurial venture that overlaps with parent-corporation’s industry, compared to a venture that does not operate in parent-corporation’s industry’ (Dushnitsky and Shaver 2009: 1050). Dushnitsky and Shapira (2010) focus their attention on investment practices and performance of corporate and independent venture capitalists. The paper investigates the three elements of the principal-agent framework, thus providing direct evidence that compensation schemes (incentives) shape investment practices (managerial action), and ultimately investors’ outcome (performance). They observe a performance gap between corporate investors and their independent counterparts. This gap is sensitive to CVC’s compensation system irrespective of whether the gap is positive or negative. ‘In other words, the ‘compensation effect’ may manifest itself in the form of increasing a positive performance differential—as we find—or as reducing a negative gap’ (Dushnitsky and Shapira 2010: 1011). Moreover, the scholars study the association between incentives and performance and they show a direct relationship between incentives and the actions managers undertake. <<They argue that there exists a ‘disparity between the number of participants in venture capital syndicates that involve a corporate investor, and those that consist solely of IVCs. The disparity shrinks substantially, however, for a subset of CVCs that compensate their personnel using performance pay. We find a parallel pattern when analyzing the relationship between compensation and another investment practice, staging of investment’ (Dushnitsky and Shapira 2010: 990). Gaba and Meyer (2008) propose and test a mid-range theory explaining the incursion of venture capital practices into the Information Technology sector of the U.S. economy, and their subsequent diffusion in the form of corporate venture capital programs. They analyze the contagion processes whereby practices originating in one organizational population spread into and diffuse within a second. Their argued that: ‘endemic innovations spread into adjacent organizational populations through two different forms of contagion. The first, cross-population contagion, flows through close interpersonal relations that afford direct exposure to the innovation, observation of its tangible payoffs, and inductive learning of its innovative practices… We further theorized that a second set of diffusion mechanisms starts to operate once an endemic innovation takes root in the new setting. Contagion within the new population begins, supplementing without necessarily supplanting the initial cross population contagion process’ (Gaba and Meyer, 2008: 994). Through a study of six corporate venture capital programs, Souitaris et al. (2012) explain how new organizational units resolve competing forces from two different institutional environments. They develop an inductive, qualitative study that started as an investigation of CVC practices. Their study aims to explore how CVCs organize their investment activities, the conditions explaining the variance in the organizational structures of CVC units and How new organizational subunits resolve competing forces from different institutional environments (Souitaris et al., 2012: 480). Authors’ conclusion are that In the context of CVCs, there exists a dichotomy between organic and mechanistic structures. Findings show that it is the environment with which the subunits align to determine the adopted system of practices. Specifically CVC units aligning with their parent (exhibiting endo-isomorphism) appear more likely to adopt a mechanistic structure. Instead, units aligning with VCs (exhibiting exo-isomorphism) appear more likely to adopt an organic structure (Souitaris et al., 2012:). In another important article, Dokko and Gaba (2012) examine career experiences of CVC managers and practice variation. Authors sustain that when organizations adopt new practices, the practices are often modified to fit the new context. They argue that managers who implement new practices modify them, and that the extent of practice variation is determined by the experience with the practice itself and a form of experience that enables assessment of the fit between the practice and the adopting firm>> (Dokko and Gaba, 2012: 563). The primary objective of this study was to investigate the effect of individuals’ career experiences on the extent of practice variation. Authors tested this arguments by observing a sample of 93 IT firms with CVC units. IT firms are regarded as an appropriate sample for testing our hypotheses, because firms in the IT sector account for more than three-quarters of all CVC investments in the 1990s (Gaba & Meyer, 2008). Moreover, focusing on IT firms exclusively allow them to control for unobserved heterogeneity at the industry level (Dokko and Gaba, 2012: 569). They develop a theoretical framework that specifies practice-specific and fit-specific prior career experiences of implementing managers as predictors of how much practices will vary after adoption (Dokko and Gaba, 2012: 577). They conceptualize ‘the extent of practice variation in terms of both goal orientation and operational strategies of practices. Drawing on organizational learning theory, we argued that different types of career experiences confer specific knowledge and mental models that in turn influence practice variation. Practice-specific experience leads to a more faithful replication of an adopted practice, while fit-specific experience enables assessment of fit between the practice and the adopter, leading to greater modification of the adopted practice’ (Dokko and Gaba, 2012: 578). In this branch is possible to consider an article of Weber and Weber (2010). They carry out an explorative study of CVC activity with a specific focus on social capital and knowledge relatedness as promoters of organizational performance. They combine social capital theory with the knowledge-based view of the firm and thereby demonstrate the interrelatedness and combined importance of the two concepts. Their proposed model show that social capital and knowledge relatedness, together referred to as “relational fit,” facilitate knowledge transfer and creation, which in turn positively influence organizational performance. Their model analyzes the influence of relational fit on German corporate venture capital units (CVCs) and their portfolio companies. Findings show that relational fit facilitates knowledge transfer and creation, and this in turn positively influences organizational performance (but CVC/corporate performance only to a limited extent) (Weber and Weber, 2010). Other studies focalize attention on CVC as a strategy for external innovation (e.g. Ernst, Witt and Brachtendorf, 2005). They investigate 21 corporate venture capital (CVC) units of large corporations in Germany and if the respective CVC programs pursue the strategic objective to leverage external innovation and if these programs are managed accordingly. They found that the majority of German corporate venture programs follow mixed objectives and are not organised and managed as suggested in the literature. They conclude that a short term focus on financial objectives of these CVC programs prohibits the achievement of long-term strategic benefits from external innovation. Actually, CVC programs seem to be too dependent on the corporate mothers. This is especially true for CVCCs that receive their funds in the form of an yearly budget with no assurance that they will continue to exist next year (Ernst, Witt and Brachtendorf, 2005: 241). Another important article in this branch is the Engel’s one (2011). The author investigates identifies ten leading strategies employed by venture capitalists and entrepreneurs to test new ideas and commercialize innovations quickly. They are: Invest in Teams, Invest in Markets, Eliminate Pain, Focus On Customer Development, Not Product Development, Dedicate Resources in Stages, Fail Fast, Speed is Everything, Pour It On, Offer No Lifeboats, Be Always Selling But Never For Sale. In the discussion section, Engel identifies three broad issues deserving further attention. Specifically, ‘1. The most disruptive innovations are not technical or product innovations alone. Rather, they are a combination of technical and business model innovations; 2. Many of the inputs of innovation management in the venture capital model rely on a market orientation and rapid-cycle innovations managed by superior teams; 3. The venture capital model provides a garden of opportunity for partnerships, collaborations, and acquisitions. A Chief Technology Officier who is conversant with the venture model can be a powerful force in attracting the right opportunities to the enterprise’ (Engel, 2011: 42-43). Another important contribution is developed by Napp and Minshall (2011). They present a paper based on nine in-depth case studies that analyze how to Successfully implement a corporate venturing program and the challenges, CV Capitalists need to face, from setting the right mixture of strategic goals and operational implementation to measuring outcomes and capturing value. Their findings support the idea that ‘successful CVC programs clearly define objectives, roles, and responsibilities and involve a wide range of business functions across hierarchies and business units in the corporate venturing process. Maximizing exposure of the company to venturing activities helps the company to capture the full strategic value of these companies, while clear communication of objectives and responsibilities makes the venturing effort more targeted and thus more likely to succeed’ (Napp and Minshall, 2011: 35-36). The relationship between Hewleett-Pakard (HP) and a leading VC firm is analyzed by Waites and Dies (2006). Authors study the strategic relationship between HewlettPackard Labs and the venture capital firm Foundation Capital. This relationship is built around the unique needs of a large corporate research organization, and is not intended to replace or substitute for on-going relationships between HP's business organizations and the venture capital community. ‘The relationship has enabled both firms to understand more clearly the fundamental differences in their two different innovation models, and it is suggested that other large central research labs could benefit from a similar relationship. HP Labs, for instance, has become more selective about investments in promising new technologies, and has been able to propose more focused market entry strategies for several of its new technologies. There are also ways to achieve such benefits without actually establishing a formal relationship’ (Waites and Dies, 2006: 20). How can a technology-savvy company better leverage the innovative ideas coming out of its laboratories? Chesbrough and Socolof (2000) analyze Lucent Technologies’ New Ventures Group and show how Lucent blends venture capital and internal development models to speed the transition from the lab to the market. Lucent Technologies have been considering the use of CVC from 1996 for three reasons: 1. to uncover new vehicles for increasing its growth; 2. to develop new mechanisms for leveraging its unparalleled technology base across multiple new business opportunities; 3. to increase the rate at which it commercializes its technologies, and it requires a catalyst to move technology out of the lab and into the market more rapidly. After a deep analysis of Lucent’s activities, Chesbrough and Socolof underline both the challenges and the opportunities of using Venture Capital model for these purposes. They claim that ‘the challenge is to balance the forces of the venture capital model with those of an internal corporate development model. The New Ventures Group's experience to date suggests that balancing these forces is difficult but that there are rewards to the organization for doing so. These include the discovery of new sources of growth, the ability to leverage internal technology across multiple businesses, and the ability to stimulate cultural change within the organization’ (Chesbrough and Socolof, 2000: 13) CONCLUSIONS Over the past twelve years, empirical studies have examined the CVC phenomenon. These studies have been conducted in some different national contexts. Particularly researchers have focused on the innovation impact of these activities, while continuing to examine its financial contribution. Instead for some scholars CVC is viewed as an important element of corporate strategy, not a mere investment opportunity. For these reasons the literature is not always as clear as it would be desirable in defining the relevant unit of analysis and this often makes comparisons across studies very difficult. In fact, findings present a fragmented state of affair with a proliferation of different perspectives. This result suggests that this topic deserves further attention and is a fertile ground of investigation. Results provide evidence that a serious reflection on is needed. But this is a partial explanation for inconsistent and contradictory findings about this phenomenon. In fact, this analysis can be extended and improved in several ways. Two first options is to enlarge the scope and the times pan of the review, and/or to selected other specific journals. REFERENCES Allen, S.A., Hevert, K.T. (2007), “Venture capital investing by information technology companies: Did it pay?”, Journal of Business Venturing, Vol. 22, No. 2, pp. 262-282. Benson, D. and Ziedonis, R.H., (2009), Corporate Venture Capital as a Window on New Technologies: Implications for the Performance of Corporate Investors When Acquiring Startups, Organization Science, Vol. 20, pp. 329-351. Chesbrough, H. W. (2002), “Making sense of corporate venture capital”, Harvard Business Review, Vol. 80, pp. 90–99. Chesbrough, H. W. (2000), “Designing Corporate Venture in the Shadow of Private Venture Capital”, California Management Review, Vol. 42, No. 3, pp. 31–49. Chesbrough, H. W., and Socolof, J.S. (2002), “Creating New Ventures From Bell Lab Technologies”, Research Technology Management, Vol. 43, No. 2, pp. 13-17 Cumming, D., Fleming, G., and Schwienbacher, A. (2009), “Corporate Relocation in Venture Capital Finance”, Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, Vol. 33, No. 5, pp. 1121-1155. Dokko, G. and Gabba, V. (2012), “Venturing Into New Territory: Carreer Experiences of Corporate Venture Capital Managers and Practice Variation”, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 55, No. 3, pp. 563-583 Dushnitsky, G. (2011), “Riding the Next Wave of Corporate Venture Capital”, Business Strategy Review, Vol. 22, No. 3, pp. 44-49 Dushnitsky, G. and Lenox, M. J. (2006), “When does corporate venture capital investment create firm value?”, Journal of Business Venturing, Vol. 21, No. 6, pp. 753-772 Dushnitsky, G. and Lenox, M. J. (2005), “When do firms undertake R&D by investing in new ventures?”, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 26, pp. 947–965. Dushnitsky, G. and Shapira, Z. (2010), “Entrepreneurial Finance Meets Oranization Reality: Comparing Investment Practices ad Performance of Corporate and Indipendent Venture Capitalists”, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 31, pp. 9901017. Dushnitsky, G. and Shaver, J.M. (2009), “Limitation to Interorganizational Knowledge Acquisition: the Paradox of Corporate Venture Capital”, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 30, pp. 1045-1064. Engel, S.J. (2011), “Accelerating Corporate Innovation: Lessons From the Venture Capital Model”, Research Technology Management, Vol. 54, No. 3, pp. 36-43 Ernst, H., Witt, P. and Brachtendorf, G. (2005), “Corporate venture capital as a strategy for external innovation: an exploratory empirical study”, R&D Management, Vol. 35, No. 3, pp. 233-242. Fox, L. (2003) “Corporate VC gets smaller but wiser”, Electronic Business, Vol. 29, No. 5, p 18-20 Gaba, V. and Mayer, A.D. (2008), “Crossing the Organizational species Barrier: How Venture Capital Practices Infiltrated the Information Technology Sector”, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 51, No. 5, pp. 976-998. Gompers, P. A. (2002), “Corporations and the financing of innovation: The corporate venturing experience”, Economic Review, Vol. 87, No. 4, pp. 1-17. Gompers, P. A. and Lerner, J. (2000), “The determinants of corporate venture capital successes: organizational structure, incentives, and complementarities”, in Morck, R. (Ed.), Concentrated Corporate Ownership, Cambridge, MA, University of Chicago Press. Griliches, Z. (1979), “Issues in assessing the contribution of research and development to productivity growth”, Bell Journal of Economics, Vol. 10, No. 1, pp. 92116.Huber, G.P. (1991), “Organizational learning: the contributing processes and the literatures”, Organization Science, Vol. 2, No. 1, pp. 88-115. Keil, T. (2002), External Corporate Venturing: Strategic Renewal in Rapidly Changing Industries, Westport, CT: Quorum. Keil, T. (2004), “Building External Corporate Venturing Capability”, Journal of Management Studies, Vol. 41, No. 5, pp. 799-825. Keil, T., Autio, E., and George, G. (2008), “Corporate Venture Capital, Disembodied Experimentation and Capability Development”, Journal of Management Studies, Vol. 45, No. 8, pp. 1475-1505. Keil, T., Maula, M., Schildt, H., Zahra, S.A. (2008), “The effect of governance mode and relatedeness of external business development activities on innovative performance”, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 29, No. 8, pp. 895-907. Levitt, B. and March, J.G. (1988), “Organisational learning”, Annual Review of Sociology, Vol. 14, pp. 319-340. Linton, J.(2006), “Ranking of technology and innovation management”, Technovation, Vol. 26, No 3, pp. 285–287. Markman, G.D., Siegel D.S., and Wright, M. (2008), “Research and Technology Commercialization”, Journal of Management Studies, Vol. 45, No. 8, pp. 1401-1423 McNally, K. (1997), “Corporate Venture Capital: Bridging the Equity Gap in the Smalt Business Sector”, Studies in Small Business, vol. 2, London: Routledge. Meglio O., Risberg A. (2011), “The (Mis)measurement of M&A performance. A systematic narrative literature review”, Scandinavian Journal of Management, Vol. 27, N°4, pp. 418-433. Muller, C., Fujiwara, T., and Herstatt, C. (2004), “Sources of Bioentrepreneurship: The Case of Germany and Japan”, Journal of Small Business Management, Vol. 42, No. 1, pp. 93-101 Napp, J.J. and Minshall, T. (2011), “Corporate Venture Capital Investments for Enhancing Innovation: Challenges and Solutions”, Research Technology Management, pp. 27-36.Narayanan, V.K., Yang, Y., and Zahra, S.A. (2009), “Corporate venturing and value creation: A review and proposed framework”, Research Policy, Vol. 38, No. 1, pp. 58-76 Park, H.D., and Steensma, H.K. (2012), “When Does Corporate Venture Capital Add Value For New Vetures?”, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 33, pp. 1-22 Roberts, E.B. and Berry, C.A. (1985), “Entering new business: selecting strategies for success”, Sloan Management Review, Vol. 26, No. 2, pp.57-71. Schildt, H.A, Maula, M.V.J. and Keil, T. (2005), “Explorative and Exploitative Learning from External Corporate Ventures”, Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, Vol. 29, No. 4, pp. 493-515. Souitaris, V., Zerbinati, S. and Liu, G. (2012), “Which Iron Cage? Endo- And Exoisomorphism in Corporate Venture Capital Programs”, Academy of Management Journal, Vo. 55, No. 2, pp. 477-505 Wadhwa, A. and Kotha, S. (2006), “Knowledge creation through external venturing: evidence from the telecommunications equipment manufacturing industry”, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 49, pp. 819–835. Waites, R., and Dies G. (2006), “Corporate Research and Venture Capital Can Learn From Each Other”,Research Technology Management, Vol. 42, No. 2, pp. 20-24 Weber, C., and Weber, B. (2010), “Social Capital and Knowledge Relatedness as Promoters of Organizational Performance”, International Studies of Management and Organization, Vol.40, No. 3, pp. 23-49