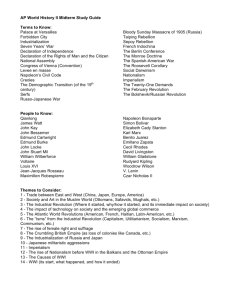

AP European History - Hinsdale Central High School

AP European History 2014-15

Unit 8—Industry and Revolution, 1750-1850

Study Guide and Terms

1. Describe rural manufacture, cottage industry, and the putting-out system. What were the advantages and disadvantages of the putting-out system?

2. Why did the Industrial Revolution occur in Great Britain first? List the advantages that

Britain possessed.

3. Explain how incremental technological innovations transformed coal mining, iron production, and cloth manufacture. Who were some of the important entrepreneurs/inventors and their accomplishments? What was the role of managers and industrialists?

4. Weigh the evidence on both sides (pro and con) and assess industrialization's overall impact: come to a conclusion and support it. Discuss problems of urbanization for the environment and how reformers addressed these. What impact did it have on the class structure and family life?

5. Compare the industrialization of the Continent with that of Great Britain. Why is

France's experience called "industrialization without revolution"? What obstacles did

Germany face in its path to industrialization and how were they overcome? Account for the lack of industrialization in many areas of Europe.

6. What responses were offered to the problems caused by industrialization? Explain the ways in which workers responded to industrialization.

7. What three principles shaped the Congress of Vienna's settlement to the Napoleonic

Wars? Identify the participants in the Congress of Vienna, their nations' goals, and what provisions were enacted as a result of the negotiations.

8. How was the period 1815-48 one of "Restoration"? How did developments in the various

European nations reflect the Conservative direction of politics? Identify the revolutionary movements Europe faced in the period 1820-48. How did Great Britain stave off revolution?

9. Identify specific goals, beliefs, and leaders of Liberalism, socialism, and nationalism.

How was nationalism related to the other two? Which classes or groups might support these ideologies?

10. How was Romanticism a response to the Enlightenment? Analyze how it reflected the social, economic, and political concerns of the first half of the nineteenth century.

11. Account for the Revolutions of 1848. Explain the goals and results of the centers of revolution in 1848. How do you explain the frustration of Liberal, nationalist, and worker goals? What is the importance of 1848? Why was this called a "turning point at which history failed to turn."

Terms

Richard Arkwright (1732-92)

Combination Acts

Factory Act, 1833 flying shuttle

James Hargreaves (d. 1778)

John Kay (1704-64)

Thomas Newcomen (1663-1729)

Abraham Darby (1678-1717)

Matthew Boulton (1728-1809)

Eli Whitney (1765-1825)

Robert Owen (1771-1858)

Poor Law, 1834 spinning jenny water frame

James Watt (1736-1819) enclosure cottage industry/putting-out system metallurgy improvements railroads urbanization

Zollverein protectionism

Ten Hours Act (1847)

Mines Act (1842)

Public Health Act (1848)

Crystal Palace Exhibition, 1851 domesticity

Reform Act of 1832 strikes proletariat

Peterloo Massacre (1819)

Chartism

Corn Laws utopian socialism

Congress of Vienna (1814-15)

Alexander I (1777-1825)

Talleyrand (1754-1838)

Klemens von Metternich (1773-1859)

Holy Alliance/Quadruple Alliance

Concert of Europe

Liberalism

Great Hunger, 1840s

John Stuart Mill (1806-73)

Giuseppe Mazzini (1805-72)

Georg Friedrich List (1789-1846)

Ludwig von Beethoven (1770-1827)

Romanticism

Victor Hugo (Hunchback, Les Mis)

Conservatism

Carlsbad Decrees (1819) socialism

Henri de Saint-Simon (1760-1825)

Pierre Joseph Proudhon (1809-65)

Charles Fourier (1772-1837)

July Revolution (1830)

Charles X (1824-30)

Louis Phillipe (1830-48)

Belgian independence, 1831

Second Republic (1848-50)

Paris Commune

Louis Kossuth (1802-94)

Frankfurt Parliament

Georg Wm. Friedrich Hegel (1770-1831)

William Wordsworth (1770-1850)

Johann Goethe (1749-1832)

Liberty Leading the People (1831)

Greek independence proletariat

Flora Tristan (1801-44)

"banquet" campaign

Napoleon III

Silesian weavers

Friedrich Engels (1820-95), Condition of

the Working Classes in England (1845)

Thomas Malthus (1766-1834)

David Ricardo (1772-1823)

AP European History 2014-15

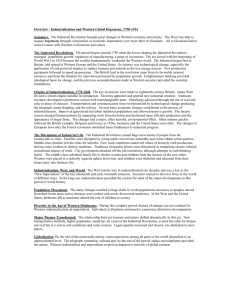

Unit 8—Industry and Revolution, 1750-1850

If you rank the important developments in world history, the Industrial Revolution would make almost everyone's Top Ten. Technology "drives" our society; without it we are virtually helpless. Many inventions from the past two hundred years have changed how humans think of themselves, others, and their environment, far beyond their intended purpose. The automobile is one such invention and symbolic of our suburban upbringing.

Many of you don't yet have your driver's license, but you are soon to realize how dependent the automobile makes us. In the suburbs you cannot function without a car.

Since the age of sixteen, I have driven about 850,000 miles—or the equivalent of circumnavigating the earth twenty-nine times—commuting to work (I drove 130 miles a day for a year), visiting girlfriends, taking vacations, running errands, making doctors' appointments, taking friends to the airport, and just "cruising." Cars have opened up new experiences, increased my mobility, advanced my career, made friends more accessible, and generally augmented my freedom. But this convenience has come at the cost of headaches and precious time: licenses, registration, emissions tests, plates, brake jobs, dead batteries, oil changes, toll booths, alignments, rush hour traffic on the Tri-State, burned-out lights, construction, traffic tickets, accidents, recovery from seedy tow lots, unexpected repairs, annoying car salesmen...In fact, a recent study by a national transportation group shows that Americans spend more to maintain their cars on average than on their housing!

As they have for me, automobiles have profoundly changed American society. While cars may be celebrated in the songs of Bruce Springsteen and mirror the abovementioned benefits writ large, they have also contributed to modern ills. Distance has lost its charm, the interstate system has destroyed the small towns of rural America, smog fills the air, central cities have decayed with the onslaught of suburbanization, mall culture and consumerism reign supreme, and in general our relatively easy access to distances once considered remote has broken down our sense of place and the authority of family and community.

Similar praises and criticisms can be made of the television. On one hand, it brings us into contact with the whole world, expands our visual repertoire, entertains and informs, and generally makes us feel part of something larger than our immediate surroundings.

Yet the "idiot box" has also contributed to a sense of rootlessness in American society.

Designed mostly for profit and consumption, the medium surpasses family, church, and community in its authority to shape (some say pervert) our morals, determine our language and fashion, inure us to violence, and alienate us from our families and neighbors (whom we no longer look to as a source of entertainment and identity). Some believe technology equals progress, while others fear its capacity to destroy traditional ways they cherish. The truth lies somewhere in between. Certainly technology has improved our material comforts and quality of life; few people if given the chance would want to return to the sixteenth or seventeenth centuries with their uncertainty, disease, and filth. But to be informed citizens we must understand not only technology but the subtle impact it can have upon our relationships, political institutions, and values.

The transformations in industry and politics (French Revolution) mark a watershed in

European history. The "Dual Revolution" produced most of our great modern inventions, from affordable underwear to democracy, as well as colored every issue of the first half of the nineteenth century. Indeed, the Age of Revolution ushered in our modern world and continues to this day.

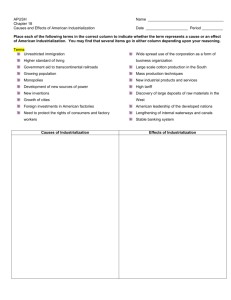

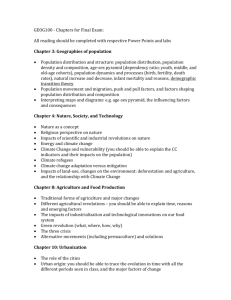

Unit Big Ideas

1. Industrialization in Europe was a double-edged sword that, on one hand, generated a rising standard of living for many, but on the other, caused unforeseen social problems.

2. The French and Industrial Revolutions set the issues for the first half of the nineteenth century. Excluded groups struggled for power and expressed their goals through new political philosophies of change. Meanwhile, those in power strove to maintain the status quo through a combination of repression and halting reform.

Syllabus

Thur., Dec. 11: Read pp. 636-41, 643-54 in text for Friday.

Fri., Dec. 12: Finish FR practice DBQ; introduction to IR with documents (Sherman). Start

invention notecard and read pp. 660-67.

Mon., Dec. 15: Why GB? activity and debate. Overview of continental industrialization.

Explain Urban Game. Finish notecard and begin Urban Game.

Tues., Dec. 16: Create web based on inventions. Finish Urban Game and begin reading pp.

654-60, 665 (doc.), 692-96, 682-83 in text. Use text and other resources for research on assigned response to industrialization.

Wed., Dec. 17: View “Mill Times” and discuss problems of industry. Finish reading pp. 654-

60, 665 (doc.), 692-96, 682-83 in text. Use text and other resources for research on assigned response to industrialization.

Thur., Dec. 18: Visit computer lab to work on ideologies pamphlet and presentation. Read pp. 672-73, 680-81, 684-88 in text and work on ideologies pamphlet/presentation.

Fri., Dec. 19: Presentations on responses and discussion of industrial issues. Read pp. 674-

80 in text over break.

WINTER BREAK! SEE SHAREPOINT FOR EXTRA CREDIT ASSIGNMENT.

Mon., Jan. 5: Visit from Klemens von Metternich and activities on Congress of Vienna.

Finish ideologies pamphlet/presentation.

Tues., Jan. 6: Presentation on ideologies. Read pp. 681 and 684 and make baseball card

on Romanticism.

Wed., Jan. 7: Activities on Romanticism; baseball card exchange. Read pp. 688-92, 696-

700 in text; prepare for forum on revolutions of 1848.

Thur., Jan. 8: Forum on revolutions of 1848. Prepare for Industrial Revolution debate;

study for final exam.

Fri., Jan. 9: In-class DBQ for Final Exam. Study for final exam.

Sat. Jan. 10: REVIEW FOR SEMESTER EXAM IN LIBRARY. 8:15-11:30 a.m.

Mon., Jan. 12: IR Debate and/or go over DBQ.

Key Concept 3.1

The Industrial Revolution spread from Great Britain to the continent, where the state played a greater role in promoting industry.

The transition from an agricultural to an industrial economy began in Britain in the 18th century, spread to France and Germany between 1850 and 1870, and finally to Russia in the 1890s. The governments of those countries actively supported industrialization. In southern and eastern Europe some pockets of industry developed, surrounded by traditional agrarian economies. Though continental nations sought to borrow from and in some instances imitate the British model — the success of which was represented by the Crystal Palace Exhibition in 1851 — each nation’s experience of industrialization was shaped by its own matrix of geographic, social, and political factors. The legacy of the revolution in France, for example, led to a more gradual adoption of mechanization in production, ensuring a more incremental industrialization than was the case in

Britain. Despite the creation of a customs union in the 1830s, Germany’s lack of political unity hindered its industrial development. However, following unification in 1871, the German Empire quickly came to challenge British dominance in key industries, such as steel, coal, and chemicals.

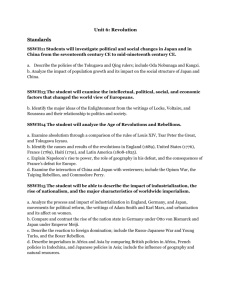

Key Concept 3.2

The experiences of everyday life were shaped by industrialization, depending on the level of industrial development in a particular location.

Industrialization promoted the development of new socioeconomic classes between 1815 and 1914.

In highly industrialized areas, such as western and northern Europe, the new economy created new social divisions, leading for the first time to the development of self-conscious economic classes, especially the proletariat and the bourgeoisie. In addition, economic changes led to the rise of trade and industrial unions; benevolent associations; sport clubs; and distinctive class-based cultures of dress, speech, values, and customs. Europe also experienced rapid population growth and urbanization that resulted in benefits as well as social dislocations. The increased population created an enlarged labor force, but in some areas migration from the countryside to the towns and cities led to overcrowding and significant emigration overseas.

Industrialization and urbanization changed the structure and relations of bourgeois and workingclass families to varying degrees. Birth control became increasingly common across Europe, and childhood experience changed with the advent of protective legislation, universal schooling, and smaller families. The growth of a “cult of domesticity” established new models of gendered behavior for men and women. Gender roles became more clearly defined as middle-class women withdrew from the work force. At the same time, working-class women increased their participation as wage-laborers, although the middle class criticized them for neglecting their families.

Industrialization and urbanization also changed people’s conception of time; in particular, work and leisure were increasingly differentiated by means of the imposition of strict work schedules and the separation of the workplace from the home. Increasingly, trade unions assumed responsibility for the social welfare of working-class families, fighting for improved working conditions and shorter hours. Increasing leisure time spurred the development of leisure activities and spaces for bourgeois families. Overall, although inequality and poverty remained significant social problems, the quality of material life improved. For most social groups, the standard of living rose; the availability of consumer products grew; and sanitary standards, medical care, and life expectancy improved.

Key Concept 3.3

The problems of industrialization provoked a range of ideological, governmental, and collective responses.

The French and Industrial Revolutions triggered dramatic political and social consequences and new theories to deal with them. The ideologies engendered by these 19th-century revolutions — conservatism, liberalism, socialism, nationalism, and even romanticism — provided their adherents with coherent views of the world and differing blueprints for change. For example, utopian socialists experimented with communal living as a social and economic response to change. The responses to socioeconomic changes reached a culmination in the revolutions of 1848, but the failure of these uprisings left the issues raised by the economic, political, and social transformations unresolved well into the 20th century.

Nationalism acted as one of the most powerful engines of political change, inspiring revolutions as well as campaigns by states for national unity or a higher degree of centralization. Early nationalism emphasized shared historical and cultural experiences that often threatened traditional elites. Over the nineteenth century, leaders recognized the need to promote national unity through economic development and expanding state functions to meet the challenges posed by industry.

Key Concept 3.4

European states struggled to maintain international stability in an age of nationalism and revolutions.

Following a quarter-century of revolutionary upheaval and war spurred by Napoleon’s imperial ambitions, the Great Powers met in Vienna in 1814-15 to re-establish a workable balance of power and suppress liberal and nationalist movements for change. Austrian Foreign Minister Klemens von

Metternich led the way in creating an informal security arrangement to resolve international disputes and stem revolution through common action among the Great Powers. Nonetheless, revolutions aimed at liberalization of the political system and national self-determination defined the period from 1815 to 1848.

The revolutions that swept Europe in 1848 were triggered by poor economic conditions, frustration at the slow pace of political change, and unfulfilled nationalist aspirations. At first, revolutionary forces succeeded in establishing regimes dedicated to change or to gaining independence from greatpower domination. However, conservative forces, which still controlled the military and bureaucracy, reasserted control. Although the revolutions of 1848 were, as George Macaulay

Trevelyn quipped, a “turning point at which modern history failed to turn,” they set the stage for a subsequent sea change in European diplomacy. A new breed of conservative leader, exemplified by

Napoleon III of France, co-opted nationalism as a top-down force for the advancement of state power and authoritarian rule in the name of “the people.” Further, the Crimean War (1853-1856), prompted by the decline of the Ottoman Empire, shattered the Concert of Europe established in

1815 and opened the door for the unifications of Italy and Germany.

Key Concept 3.6

European ideas and culture expressed a tension between objectivity and scientific realism on one hand, and subjectivity and individual expression on the other.

The romantic movement of the early 19th century set the stage for later cultural perspectives by encouraging individuals to cultivate their uniqueness and to trust intuition and emotion as much as reason. Partly in reaction to the Enlightenment, romanticism affirmed the value of sensitivity, imagination, and creativity, and thereby provided a climate for artistic experimentation. Later artistic movements such as Impressionism, Expressionism, and Cubism, which rested on subjective interpretations of reality by the individual artist or writer, arose from the attitudes fostered by romanticism. The sensitivity of artists to non-European traditions that imperialism brought to their attention also can be traced to the romantics’ emphasis on the primacy of culture in defining the character of individuals and groups.

Many writers saw humans as governed by spontaneous, irrational forces and believed that intuition and will were as important as reason and science in the search for truth. In art, literature, and science, traditional notions of objective, universal truths and values increasingly shared the stage with a commitment to and recognition of subjectivity, skepticism, and cultural relativism.

European History—AP

Industrial Revolution

Invention Report

As before, you will receive a 6x9 notecard in which to complete a report on an invention or process

THAT WAS DEVELOPED FROM 1750-1850. Your task will be twofold: 1) briefly trace its history and development and 2) explain its impact on society. Take notes on one side of the card, and provide a substantive analytical paragraph and bibliography on the other. In some cases, your "invention" may be more of a process (like the development of the factory system), in others, a significant one-time breakthrough (like the spinning jenny). In explaining the IMPACT of the invention, consider factors like the standard of living, working conditions, nature of the work itself, impact on consumer, family life/children, urban life. There are several websites at SharePoint for use in research. This is worth 20 points and is due Tues., Dec. 16. The topics:

1. spinning jenny

2. flying shuttle

3. water frame and (Crompton’s) mule

4. Cartwright's power loom

5. Jacquard loom

6. cotton gin

7. coal mining

8. iron and steel

9. steam engine

10. railroads

11. machine tools

12. chemical industry

13. bleaching and dyeing

14. pottery and ceramics

15. sewage and sanitation

16. hydraulic engineering/pneumatics

17. ship-building and navigation

18. canals

19. weapons

20. clocks

21. photography

22. vulcanized rubber

23. interchangeable parts

24. agriculture: fertilizers, fodder crops, new techniques, soil management, animal husbandry

25. factory organization

26. banks/finance/credit (focus on G. Britain)

27. putting-out system/cottage industry

28. Crystal Palace Exhibition