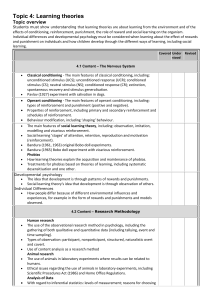

- Islamic

advertisement