Exchange Rate Risk Consider an investment in risk

Exchange Rate Risk

Consider an investment in risk-free British government bills paying 10% annual interest in British pounds. While these U.K. bills would be the risk-free asset to a British investor, this is not the case for a U.S. investor. Suppose, for example, the current exchange rate is $2 per pound, and the U.S. investor starts with

$20,000. That amount can be exchanged for £10,000 and invested at a riskless 10% rate in the United Kingdom to provide £11,000 in one year.

What happens if the dollar–pound exchange rate varies over the year? Say that during the year, the pound depreciates relative to the dollar, so that by year-end only $1.80 is required to purchase £1. The £11,000 can be exchanged at the year-end exchange rate for only $19,800 (= £11,000x$1.80/£), resulting in a loss of

$200 relative to the initial $20,000 investment. Despite the positive 10% pound-denominated return, the dollar-denominated return is a negative 1%.

Pure exchange rate risk is the risk borne by investments in foreign safe assets. The investor in U.K. bills of the above example bears only the risk of the U.K./ U.S. exchange rate. We can assess the magnitude of exchange rate risk by examination of historical rates of change in various exchange rates and their correlations.

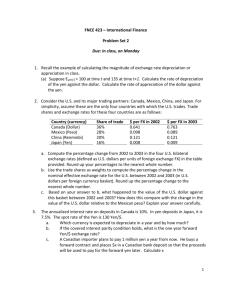

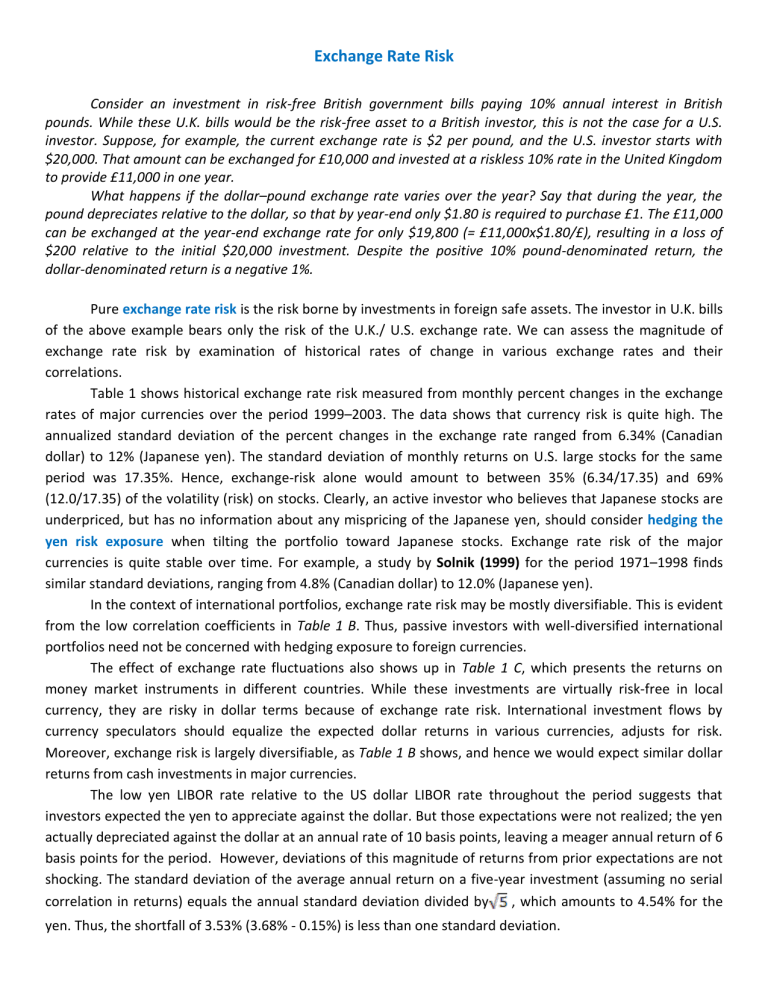

Table 1 shows historical exchange rate risk measured from monthly percent changes in the exchange rates of major currencies over the period 1999–2003. The data shows that currency risk is quite high. The annualized standard deviation of the percent changes in the exchange rate ranged from 6.34% (Canadian dollar) to 12% (Japanese yen). The standard deviation of monthly returns on U.S. large stocks for the same period was 17.35%. Hence, exchange-risk alone would amount to between 35% (6.34/17.35) and 69%

(12.0/17.35) of the volatility (risk) on stocks. Clearly, an active investor who believes that Japanese stocks are underpriced, but has no information about any mispricing of the Japanese yen, should consider hedging the yen risk exposure when tilting the portfolio toward Japanese stocks. Exchange rate risk of the major currencies is quite stable over time. For example, a study by Solnik (1999) for the period 1971–1998 finds similar standard deviations, ranging from 4.8% (Canadian dollar) to 12.0% (Japanese yen).

In the context of international portfolios, exchange rate risk may be mostly diversifiable. This is evident from the low correlation coefficients in Table 1 B. Thus, passive investors with well-diversified international portfolios need not be concerned with hedging exposure to foreign currencies.

The effect of exchange rate fluctuations also shows up in Table 1 C, which presents the returns on money market instruments in different countries. While these investments are virtually risk-free in local currency, they are risky in dollar terms because of exchange rate risk. International investment flows by currency speculators should equalize the expected dollar returns in various currencies, adjusts for risk.

Moreover, exchange risk is largely diversifiable, as Table 1 B shows, and hence we would expect similar dollar returns from cash investments in major currencies.

The low yen LIBOR rate relative to the US dollar LIBOR rate throughout the period suggests that investors expected the yen to appreciate against the dollar. But those expectations were not realized; the yen actually depreciated against the dollar at an annual rate of 10 basis points, leaving a meager annual return of 6 basis points for the period. However, deviations of this magnitude of returns from prior expectations are not shocking. The standard deviation of the average annual return on a five-year investment (assuming no serial correlation in returns) equals the annual standard deviation divided by , which amounts to 4.54% for the yen. Thus, the shortfall of 3.53% (3.68% - 0.15%) is less than one standard deviation.

The investor in example presented could have hedged the exchange rate risk using a forward or futures contract in foreign exchange. Recall that a forward or futures contract on foreign exchange calls for delivery or acceptance of one currency for another at a stipulated exchange rate. Here, the U.S. investor would agree to deliver pounds for dollars at a fixed exchange rate, thereby eliminating the future risk involved with conversion of the pound investment back into dollars.

TABLE 1

Rates of change in the value of the U.S. dollar against major world currencies, 1999–2003

(monthly data)

A. Standard Deviation

(annualized)

Country

Currency

Euro (E) U.K. (£) Japan (¥) Australia ($A) Canada ($C)

Standard dev. 10.20 7.35 10.14 12.00 6.34

B. Correlation Matrix

Euro

U.K.

Japan

Australia

Canada

Euro

1.00

0.73

0.44

0.48

0.31

U.K.

1.00

0.32

0.32

0.23

Japan

1.00

0.37

0.26

Australia

1.00

0.75

Canada

1.00

C. Average Annual Returns from Rolling Over One-Month LIBOR Rates

Country

U.S.

Australia

Canada

U.K.

Europe

Japan

Currency

AUD

CAD

GBP

EUR

JPY

Return in

Local

Currency

3.68

5.06

4.01

4.84

3.41

0.15

Gains from

Exchange

Rates

-2.74

-3.14

-0.45

0.14

-0.10

Average

Annual

Returns in

USD

3.68

2.33

0.87

4.40

3.55

0.06

Standard deviation of the Average

Annual

Returns

5.36

2.84

3.29

4.56

4.54

Is Exchange Rate Risk Important in International Portfolios?

Table 1 revealed that changes in exchange rates are not highly correlated across countries. This feature suggests that when international portfolios are well diversified, the exchange rate component of overall risk will be effectively diminished. Another feature that would render exchange rate risk diversifiable is low correlation between changes in exchange rates and country stock returns in local currencies.

In Figure 1.1-1.3, we compare results for SD, beta coefficients and correlations with US stocks returns using dollar and local-currency returns. These graphs show that local currency SDs (Figure 1.1) are slightly lower than SDs of dollar returns, indicating the presence of exchange rate risk. Beta coefficients (Figure 1.2) are also lower on average using local currency returns, in some cases significantly so, indicating that a portion of exchange rate risk may be systematic. However, the graph for correlations with US stocks returns suggests

that may just be seeing statistical noise. The correlations of local returns appear higher on average than those of dollar returns. On balance, exchange rate risk in diversified portfolios probably is a small fraction of overall risk.

Figure 1.1. Standard Deviation of Investments across the Globe in US Dollars versus

Local Currency

Figure 1.2. Beta in $US versus Local Currency

Figure 1.3. Correlation of Returns in $US and Local Currencies 1999 - 2003