Jangama - Virgilio Siti Xoom

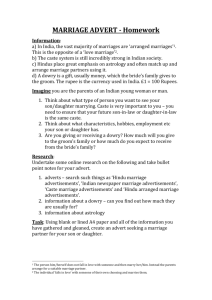

advertisement