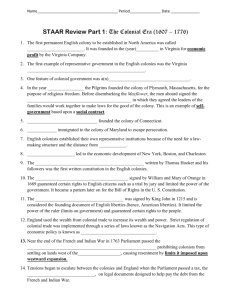

thE rOaD tO rEvOlUtIOn, 1754-1775

advertisement