Using Consumer Loans

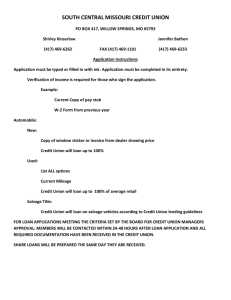

advertisement