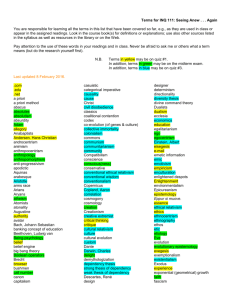

The development of relativism - Developmental Testing Service

advertisement