UBS opinion 28 September 2012

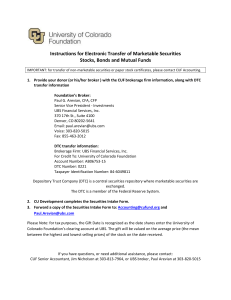

advertisement