ROCKY MOUNTAIN LIFE

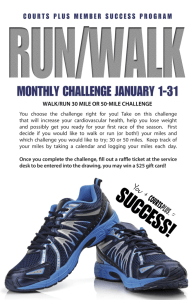

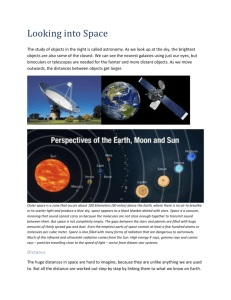

advertisement