Effects of Election Results on Stock Price Performance: Evidence

advertisement

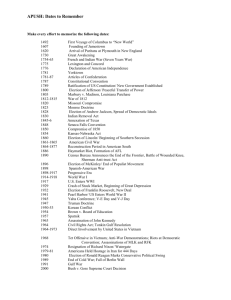

Effects of Election Results on Stock Price Performance: Evidence from 1976 to 2008 Andreas Oehler Chair of Finance, Bamberg University, Germany andreas.oehler@uni-bamberg.de Thomas J. Walker Laurentian Bank Chair in Integrated Risk Management Concordia University, Montreal, Canada, twalker@jmsb.concordia.ca Stefan Wendt Department of Finance, Bamberg University, Germany stefan.wendt@uni-bamberg.de Abstract Election results may influence corporate performance by general changes in government spending and tax changes. In addition, specific companies or sectors might benefit or suffer from sector-specific governmental decisions. Stock market participants will incorporate expectations about political change into stock prices prior to an election and adjust their opinion according to the actual decision making following the election. To date, we do not know whether both the Republican and Democratic parties are associated with particular stock price effects for certain companies or sectors and whether these effects persist over several elections. We analyze abnormal stock price returns around the U.S. presidential elections from 1976 to 2008 with focus on party-specific favoritism. The results demonstrate statistically significant (positive or negative) cumulative abnormal price returns for most industries. Most effects appear to be related to the individual presidents and changes in political decision making per se irrespective of the underlying political ideology. Key Words: Partisanship, Sector Performance, Political Economics JEL Codes: G11, G18, P16 Corresponding author 1 Effects of Election Results on Stock Price Performance: Evidence from 1976 to 2008 Abstract Election results may influence corporate performance by general changes in government spending and tax changes. In addition, specific companies or sectors might benefit or suffer from sector-specific governmental decisions. Stock market participants will incorporate expectations about political change into stock prices prior to an election and adjust their opinion according to the actual decision making following the election. To date, we do not know whether both the Republican and Democratic parties are associated with particular stock price effects for certain companies or sectors and whether these effects persist over several elections. We analyze abnormal stock price returns around the U.S. presidential elections from 1976 to 2008 with focus on party-specific favoritism. The results demonstrate statistically significant (positive or negative) cumulative abnormal price returns for most industries. Most effects appear to be related to the individual presidents and changes in political decision making per se irrespective of the underlying political ideology. Key Words: Partisanship, Sector Performance, Political Economics JEL Codes: G11, G18, P16 2 1 Introduction Election results may affect post-election corporate performance either by influencing a country’s overall economy, e.g. via changes in government spending and/or fiscal changes, or through company- or sector-specific decisions such as changes in the regulatory environment after the new administration has been established. The latter effect is typically associated with (electoral) partisanship, hereafter defined as polarized ideologies of governance and policy-making. Here, the U.S. political system is dominated by two parties: the Democrats and the Republicans (GOP). At the risk of oversimplification, Republicans are typically seen as pursuing laisser-faire capitalism, favoring low taxes and deregulation, whereas Democrats employ a more Keynesian approach, leveraging government as the catalyst for socioeconomic progress. The allocation of change, however, is not systematic across the market, and can be either beneficial or harmful for single companies/sectors. In addition, the causality between election results and economic performance is not always clearly identifiable since underlying economic conditions (particularly hardship) heavily influence public opinion and voting results (Fiorina 1991). Stock market participants will price their expectations about political change into stock prices prior to an election and adjust their opinion according to the actual political decision making after the election and inauguration took place. In the U.S., presidential elections are a key inflection point of change in the political landscape. As such, an increasing likelihood of a candidate’s victory should be reflected in stock prices. However, expectations about election results are not always clear-cut. Therefore, futures markets increase in volatility in tight elections due to uncertainty about election results and their implications (Jones 2008). Leading up to an election, information asymmetry has been shown to exist between the market and political parties. In 3 addition, He et al. (2009) report difficulties of market participants to distinguish fact from political soap-boxing due to skepticism caused by political posturing, such as short-term stimulation of the economy to reduce unemployment and increase the likelihood of re-election (Alesina and Sachs 1986). However, Wolfers and Zitzewitz (2004) document – based on evidence from prediction markets – that market mechanisms are likewise efficient at reflecting the political reality and quite accurate at predicting probabilities. In this study we examine the effects of presidential election results on the stock price performance of U.S. stock corporations and industry sectors. Moreover, we aim to identify and quantify the perceived Republican and Democrat favoritism towards or biases against specific industries. To do so, the study measures stock price sensitivity to election results for the presidential elections from 1976 to 2008. In this context, we assume that pre-election polls are not able to fully forecast election results and that the election itself will reveal new information which, in turn, will be incorporated into stock prices. Since voters and the market are historically myopic in their time frame reference, measurement across a four-year interval between elections is not representative of voter sentiment (Niskanen 1975). In addition, most significant policy changes occur in the first 90 days following the inauguration (Drazen 2001). Therefore, we measure abnormal stock price returns in different industries for a number of time windows after the respective election day. By doing so, we are able to identify both short-run (two and four weeks) and longer-run effects until up to around 100 days after the inauguration day – a time window that corresponds to approximately six months after the election day. The results show that all U.S. presidents, regardless of party, prompt abnormal company and sector returns following their elections. These effects, however, tend to be more pronounced in 4 the longer post-election time windows. Overall, our results support the hypothesis that, following a presidential election, the market corrects and thus reflects changes in the underlying governing philosophy. This is materialized through abnormal returns, the distribution of which varies in direction and magnitude. However, despite some identifiable distinctions between the political profiles of the Republican and Democratic Party it appears that change in presidential personas rather than any consistent and permanent difference in political decision making between parties influence stock and industry performance. The paper contributes to the existing literature and to the public debate in two ways. First, it is to our knowledge the first analysis of potential partisanship of the two major political parties over a horizon that spans four decades. Second, we show that companies and/or industries are influenced by single presidents rather than by fundamental and permanent differences in the governing philosophy of both parties. The paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we provide a brief review of the literature on market reactions to expected and actual election results. In Section 3, we explain the dataset used in our analysis. In Section 4, we present both the event study and the regression methodology applied in the analysis. The event study and regression results are presented in Section 5. In Section 6, we discuss the results and conclude. 2 Literature Review Empirical evidence on pre- or post-election effects on sector-specific stock price performance is scarce. Roberts (1990) finds that the stock price performance of the defense sector was positively 5 affected by an increase in the winning probability of Ronald Reagan prior to the 1980 presidential election whereas the overall market remained largely unaffected. Herron et al. (1999) document a significant influence on 15 out of 74 economic sectors as a consequence of a change in the winning probabilities of the candidates during the campaign period of the 1992 presidential election. The study of Bechtel and Füss (2010) provides some international evidence. They analyze the stock price performance and volatility of four economic sectors prior to the elections of the German parliament (Bundestag) during the 1991 to 2005 period. They find that an increasing probability of a more conservative government increases both the mean return and the volatility of the defense and the pharmaceutical sector, whereas the alternative energy sector exhibits higher returns and the consumer sector higher volatility with an increasing probability of a left-leaning government. Much more research has been conducted with regard to the effect of presidential elections on the performance of the overall U.S. stock market. Earlier studies include Niederhoffer, Gibbs, and Bullock (1970), Huang (1985), and Gärtner and Wellershoff (1995). More recent studies include Leblang and Mukherjee (2005) and Snowberg, Wolfers, and Zitzewitz (2007a). International evidence on the stock market’s reaction to elections or to electoral cycles has been provided by, e.g., Foerster and Schmitz (1997) for the effect of U.S. elections on international stock returns, by Herron (2000) and Leblang and Mukherjee (2005) for the British stock market, by Siokis and Kapopoulos (2007) for the Greek market, by Brunner (2009) for the Dutch market, and by Furió and Pardo (2010) for the Spanish market. The market reaction to political change is not limited to presidential elections but is also documented for changes in the composition of Congress. Adjustments reflect new dominance and are sensitive to apparent benefits to the economy (Snowberg, Wolfers, and Zitzewitz 2007b). Furthermore, the Republican Party follows a sharper 6 cycle pattern than the Democratic Party, indicating a tendency towards partisan reforms (Wong and McAleer 2009). Financial markets do not only attempt to forecast equity prices in relation to election results, but also interest rates, currencies, and commodity prices (see Snowberg, Wolfers and Zitzewitz 2007a, 2007b). Political partisanship, however, also influences the more macroeconomic variables such as inflation, growth, and unemployment rates as documented for the U.S. and for Europe by authors such as Hibbs (1977), Alesina, Roubini, and Cohen (1997), and Caporale and Grier (2000). Importantly, however, the causality of the influence between the economic and the political sphere flows both ways (Gerber, Huber and Washington 2009), since the market also influences policy reform through, e.g., lobbyism. Knight (2007) and Mattozzi (2008) reflect this circular relationship and analyze firm-specific stock price effects for U.S. companies that made campaign contributions to presidential candidates. While Roberts (1990) and Herron et al. (1999) analyze sector-specific effects related to a single U.S. presidential election, we analyze these effects for a total of nine presidential elections beginning with the election of 1976. 3 Data We employ data that is related to the nine elections from 1976 to 2008. The period was expressedly chosen to include only non-interrupted presidencies, providing greater consistency in 7 voter-sentiment1 leading into the subsequent election (Fiorina 1991). We use Wharton Research Data Services (WRDS) to retrieve daily stock return data (from CRSP) and the respective company characteristics (from Compustat). Company characteristics include the four-digit standard industrial classification code (SIC code), stock market capitalization, book value of debt, total assets, and net income. All company characteristics are identified based on the last reporting date prior to the respective election. Based on these data we calculate corporate leverage as the ratio of book value of debt to market capitalization, and the ratio of net income to total assets to capture pre-election corporate performance independent of the stock market. Data on the risk-free rate (the one month Treasury bill rate), and on the Fama-French factors (market premium, SMB, HML) as well as on the momentum factor are also retrieved from WRDS. After matching stock return data and company characteristics, we sort our sample of companies around each election into eight industry groups including mining (SIC codes 1000 to 1499), construction (1500 to 1999), manufacturing (2000 to 3999), transportation, communications, electric, gas and sanitary services (4000 to 4999; hereafter: transportation), wholesale trade (5000 to 5199), retail trade (5200 to 5999), finance, insurance and real estate (6000 to 6999; hereafter: financials), and services (7000 to 8999). We exclude companies with incomplete data as well as companies that operate in one of the following industries: agriculture, forestry and fishing (0100 to 0999), public administration (9000 to 9899), and non-classifiable establishments (9900 to 9999) since there are too few companies (less than 5 each) to draw meaningful conclusions. An overview of the elections and the respective number of companies in each of the industry divisions is provided in Table 1. 1 Use of voter-sentiment does not refer to preference towards either the Republican or Democratic parties, but instead attempts to curtail biases from the presidencies of John F. Kennedy (national tragedy) and Richard M. Nixon (resignation/impeachment). 8 Please insert Table 1 about here. 4 Methodology 4.1 Event study In order to determine the stock market reaction to changes in the political landscape we apply event study methodology. For each election we analyze the cumulative abnormal stock price returns in each industry for the day following the election day as well as for a 2-week, 4-week, 10-week, 18-week, and 26-week horizon following the election day. The shorter windows are chosen in order to detect any short-run effects of the new information that is transmitted to the market via the election result. The 10-week window is chosen since the tenth week is typically the last week prior to inauguration of the elected president. The 18-week and the 26-week horizons are chosen in order to detect any longer lasting effects and to determine whether the preinauguration trend changes after the actual inauguration day. Within the four weeks after the inauguration, the incumbent leader typically outlines his roadmap for the coming months. This generally includes explicitly outlining major goals and priorities for the new administration – the first opportunity to reinforce or invalidate current market assumptions (Snowberg, Wolfers, and Zitzewitz 2007a). The 26-week window after the election day also reflects the fact that the new president typically tackles the major policy reforms within the first 90-100 days in office which corresponds to around 14 weeks after inauguration (Drazen 2001). Beyond this point, upcoming mid-term elections discourage the pursuit of significant controversial changes. Daily abnormal stock price returns, ARi ,t , for each company i are calculated as 9 ARi ,t Ri ,t E Ri ,t , where Ri , t represents the actual stock price return on day t, while E Ri ,t denotes the expected stock price return on that day. E Ri ,t is calculated using the four-factor model established by Carhart (1997), E Ri ,t R f ,t i ,1 * Rm,t R f ,t i , 2 * SMBt i ,3 * HMLt i , 4 * MOMt , where R f , t represents the one month Treasury bill rate on day t, which is used as a proxy for the risk-free rate, and Rm ,t denotes the respective stock market return. SMBt and HMLt are the Fama-French size and book-to-market factor returns, and MOM t represents the momentum factor return. i ,1 , i , 2 , i ,3 , and i , 4 are estimated by regressing the excess stock price returns of company i on the market excess return, size, book-to-market, and momentum factor returns for the estimation period, which is chosen as the one-year period that ends two weeks prior to the election day. The two weeks leading up to the election are excluded since expectations about the election outcome might already be clear-cut and reflected by adjustments in stock prices. However, we still assume that pre-election polls are not able to fully forecast election results and that the election itself will reveal new information which, in turn, will be incorporated into stock prices in the post-election period. We do not use long-term pre-election betas since we need an estimate that only reflects the previous presidency in order to increase the likelihood of capturing the policy bias. 10 For the above described windows, we calculate the cumulative abnormal stock price returns as t2 CARi ,t1 ,t 2 ARi ,t t t1 where t1 denotes the day following the election day and t2 denotes the end of the 2-week, 4week, 10-week, 18-week, and 26-week event windows. Since the election day is always scheduled on the Tuesday after the first Monday in November, all relevant dates t1 and t2 represent a Wednesday. For each of the above described industry groups, we calculate industry cumulative abnormal returns, CARtindustry , as the mean value of the equally weighted cumulative abnormal stock price 1 ,t 2 returns of the single companies in the respective industry: industry t1 , t 2 CAR 1 N industry Nindustry i 1 CAR i , t1 , t 2 , where Nindustry is the number of companies in the respective industry (as presented in Table 1). The results are tested for significance by calculating t-values. 11 4.2 Regression analysis We run a regression analysis in order to determine whether the market perceives any biases of the Democratic and/or Republican parties towards certain industries. We thus form two sub-samples: one sub-sample contains all cumulative abnormal stock price returns following elections that were won by a Democratic candidate, i.e. the elections of 1976, 1992, 1996, and 2008; the other sub-sample contains all cumulative abnormal stock price returns following the elections that were won by a Republican candidate, i.e. the elections of 1980, 1984, 1988, 2000 and 2004. For each sub-sample we then run a series of regressions with the cumulative abnormal stock price return over each window (i.e., the election day and the 2-week, 4-week, 10-week, 18-week, and 26week event windows) as a dependent variable, respectively. As explanatory variables we include dummy variables for each industry group which are assigned a value of 1 if the respective company belongs to that industry and 0 otherwise; the dummy variable for the industry devision retail trade is not included in the regression and serves as a reference group since this industry has turned out in the event study as being the least influenced by the election results. The regression model is set up as follows: CARi ,t1 ,t 2 β * D * ln(mcapi ) * levi * incomei where denotes the constant, D is a vector of dummy variables for seven of our eight industry groups (mining; construction; manufacturing; transportation; wholesale trade; financials; services) and β denotes the respective vector of coefficients. We include the logarithm of the stock market capitalization for each company i, ln(mcapi), leverage, levi, and the ratio of net 12 income to total assets, incomei, in order to control for possible size, risk, and performance effects, respectively, that are independent of the stock market. 5 Results 5.1 Event study The results of the event study for the nine presidential elections from 1976 to 2008 are presented in Table 2. From each election there appears to be some – at least temporary – effect on stock price performance in a number of industries, with more statistically significant results for the elections since the 1990s which might be affected by the larger number of included companies for the more recent elections. Please insert Table 2 around here. The election of Democratic candidate James Carter in 1976 is associated with hardly any statistically significant cumulative abnormal industry returns. While the mining, transportation, financial, and service sectors appear to be somewhat positively influenced, we observe a negative effect on the manufacturing, construction, and retail sectors – for the latter two sectors at least in the longer run. The first election of Republican candidate Ronald Reagan in 1980 results in a somewhat reverse picture compared to Carter’s 1976 victory. The mining and financial sectors suffer significant (longer run) negative abnormal returns, whereas there is positive performance in the manufacturing sector. The effects on the other sectors are rather ambiguous. The reelection of Ronald Reagan in 1984 again results in negative industry returns in the mining sector. 13 This time, however, the financial sector shows significant positive performance, while all other sectors do not reveal a clear trend. The electoral victory of George H.W. Bush (Republican Party) in 1988 results in negative longerrun overall stock performance in the construction and financial sectors. For the other sectors, the picture is much less clear-cut. The first election of William J. Clinton (Democratic Party) in 1992 has a strong positive influence on nearly all industries particularly in the longer run. We document the strongest effects (more than 20 percent cumulative abnormal stock returns) for the mining, construction, transportation, and the service sectors. The other sectors (manufacturing, wholesale trade, retail trade, and financials) are also positively affected but to a lesser degree. The re-election of Clinton in 1996 leads to much more moderate stock market reaction. However, the mining, manufacturing, retail trade, and financial sectors are again positively influenced, while all other sectors are hardly affected – at least not at statistically significant levels. Republican candidate George W. Bush’s first election in 2000 results in statistically significant short-run negative returns in the mining, manufacturing, retail trade, and service sectors – a trend that is largely reversed after inauguration. The manufacturing, transportation, wholesale, financial, and service sectors exhibit significant positive long-run abnormal returns. The stock price effects following George W. Bush’s re-election in 2004 are much weaker in most industries. However, positive stock price effects can still be documented for the manufacturing, transportation, and wholesale trade sectors, as well as for the construction industry. Most industries exhibit very volatile cumulative abnormal stock returns after the election of Barack H. Obama in 2008. The performance of the mining, construction, and service sectors is negative in the first weeks after the election day followed by strong upward trends directly before and also 14 after the inauguration. For all other sectors we cannot detect a clear trend in industry performance. While we do not see consistent patterns in industry performance across all candidates of one of the two political parties, it becomes obvious that changes in the governing party result in much larger cumulative abnormal industry returns than re-elections. Interestingly, when compared across all elections, the cumulative abnormal returns tend to be more frequently on the positive than on the negative side, suggesting that stock market participants expect positive effects from changes in political decision making irrespective of the direction of these changes – an effect that is much in line with the fact that most political reform takes place at the beginning of a presidential term. 5.2 Regression analysis The results of our regression analysis are presented in Table 3. For the four elections won by a Democratic candidate, as presented in Panel A, the cumulative abnormal stock price returns hardly appear to be influenced by the industry the company belongs to. Only companies from the mining sector exhibit a short-run and statistically significant negative effect which, however, is reversed in the long-run. For all other industry dummies the coefficients are statistically largely insignificant. This means that stock market participants do not appear to expect an industryspecific bias in political decision making after the election and inauguration of a Democratic candidate per se. When combining these results with our event study results, potential industry biases are rather associated with single Democratic presidents than with the party. 15 Please insert Table 3 around here. The results for the elections won by a Republican candidate, presented in Panel B of Table 3, paint a somewhat clearer picture than the results for the Democratic candidates did. In particular, the affiliation of a company with the manufacturing, transportation, wholesale trade, and financial sectors appears to have a significant positive influence on the stock price performance after the victory of a Republican candidate. From this, we can conclude that stock market participants expect a positive influence of political decision making by a Republican candidate on these sectors. This effect, however, is largely reversed in the longer run, in particular after the inauguration date. Again, when comparing the regression results to the event study results we see that the stock market effects appear to be primarily driven by expectations with regard to single candidates than to the Republican party per se. In addition, the overall explanatory power of the regressions for both sub-samples is relatively weak. 6 Discussion and Conclusions In this study, we document that the elections of all recent U.S. presidents, regardless of their political affiliation, have prompted abnormal company and sector returns. These effects, however, are particularly pronounced when examining longer post-election time windows. We propose two potential interpretations: (1) the market remains uncertain (and does not adjust) until the president’s political priorities are clear; (2) the market struggles to reconcile the effects of political changes. This leaves us with a rather ambiguous view of market efficiency with regard to political effects. There appears to be some rationality and efficiency with regard to information 16 about actual political changes (after inauguration), but there also seem to be behavioral effects, in particular with regard to the slowness of the market reaction. Overall, our results support the hypothesis that, following a presidential election, the market corrects, and thus reflects changes in the underlying governing philosophy. This is materialized through abnormal returns, the distribution of which varies in direction and magnitude. However, despite some identifiable distinctions between the political profiles of the Republican and Democratic parties, changes in stock returns and industry performance appear to be driven by market expectations related to individual presidents rather than any consistent and permanent differences in the political decision making between the parties. 17 References Alesina, Alberto, and Jeffrey Sachs 1988. “Political Parties and the Business Cycle in the United States, 1948-1984.” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 20(1): 63–82. Alesina, Alberto, Nouriel Roubini, and Gerald D. Cohen 1997. Political Cycles and the Macroeconomy. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Bechtel, Michael M., and Roland Füss 2010. “Capitalizing on Partisan Politics? The Political Economy of Sector-Specific Redistribution in Germany.” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 42(2-3): 203–35. Brunner, Martin 2009. “Does Politics Matter? The Influence of Elections and Government Formation in the Netherlands on the Amsterdam Exchange Index.” Acta Politica 44(2): 150– 70. Caporale, Tony, and Kevin B. Grier 2000. Political Regime Change and the Real Interest Rate. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 32(3): 320–34. Drazen, Allan 2001. “The Political Business Cycle after 25 Years.” NBER Macroeconomic Annual 2000, Vol. 15: 75–138. Fiorina, Morris P. 1991. “Elections and the Economy in the 1980s: Short- and Long-Term Effects.” In Politics and Economics in the Eighties, eds. Alberto Alesina and Geoffrey Carliner. NBER Books, 17–40. 18 Foerster, Stephen R., and John J. Schmitz 1997. “The Transmission of U.S. Election Cycles to International Stock Returns.” Journal of International Business Studies 28(1): 1–27. Furió, María D., and Ángel Pardo 2010. “Politics and Elections at the Spanish Stock Market.” University of Valencia. Working Paper. Gärtner, Manfred, and Klaus W. Wellershoff 1995. “Is There an Election Cycle in American Stock Returns?” International Review of Economics and Finance 4(4): 387–410. Gerber, Alan S., Gregory A. Huber, and Ebonya Washington 2009. “Party Affiliation, Partisanship, and Political Beliefs: A Field Experiment.” The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER). Working Paper 15365. He, Yan, Hai Lin, Chunchi Wu, and Uric B. Dufrene 2009. “The 2000 Presidential Election and the Information Cost of Sensitive Versus Non-sensitive S&P500 Stocks.” Journal of Financial Markets 12(1): 54–86. Herron, Michael C. 2000. “Estimating the Economic Impact of Political Party Competition in the 1992 British Election.” American Journal of Political Science 44(2): 326–37. Herron, Michael C., James Lavin, Donald Cram, and Jay Silver 1999. “Measurement of Political Effects in the United States Economy: A Study of the 1992 Presidential Election.” Economics and Politics 11(1): 51–81. 19 Hibbs, Douglas A. 1977. “Political Parties and Macroeconomic Policy.” American Political Science Review 71(4): 1467–87. Huang, Roger D. 1985. “Common Stock Returns and Presidential Elections.” Financial Analysts Journal 41(2): 58–61. Jones, Randall J. 2008. “The State of Presidential Election Forecasting: The 2004 Experience.” International Journal of Forecasting 24(2): 310–21. Knight, Brian G. 2007. “Are Policy Platforms Capitalized into Equity Prices? Evidence from the Bush/Gore 2000 Presidential Election.” Journal of Public Economics 91(1-2): 389–409. Leblang, David, and Bumba Mukherjee 2005. “Government Partisanship, Elections and the Stock Market: Examining American and British Stock Returns, 1930-2000.” American Journal of Political Science 49(4): 780–802. Mattozzi, Andrea 2008. “Can We Insure Against Political Uncertainty? Evidence from the U.S. Stock Market.” Public Choice 137(1-2): 43–55. Niederhoffer, Victor, Steven Gibbs, and Jim Bullock 1970. “Presidential Elections and the Stock Market.” Financial Analysts Journal 26(2): 111–13. 20 Niskanen, William A. 1975. “Bureaucrats and Politicians.” Journal of Law & Economics 18(3): 617–43. Roberts, Brian E. 1990. “Political Institutions, Policy Expectations, and the 1980 Election: A Financial Market Perspective.” American Journal of Political Science 34(2): 289–310. Siokis, Fotios, and Panayotis Kapopoulos 2007. “Parties, Elections and Stock Market Volatility: Evidence from a Small Open Economy.” Economics and Politics 19(1): 123–34. Snowberg, Erik, Justin Wolfers, and Eric Zitzewitz 2007a. “Partisan Impacts on the Economy: Evidence from Prediction Markets and Close Elections.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 122(2): 807–29. Snowberg, Erik, Justin Wolfers, and Eric Zitzewitz 2007b. “Party Influence in Congress and the Economy.” Quarterly Journal of Political Science 2(3): 277–86. Wolfers, Justin, and Eric Zitzewitz 2004. “Prediction Markets.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 18(2): 107–26. Wong, Wing-Keung, and Michael McAleer 2009. “Mapping the Presidential Election Cycle in U.S. Stock Markets.” Mathematics and Computers in Simulation 79(11): 3267–77. 21 Table 1 Summary statistics President Party Election Day Mining Construction Manufacturing Transportation Wholesale Retail Financials Services James E. Carter Democrat 02.11.1976 18 5 212 12 6 3 34 17 Ronald W. Reagan Republican 04.11.1980 21 3 311 23 13 7 57 24 Ronald W. Reagan Republican 06.11.1984 49 6 554 29 36 19 110 77 George H. W. Bush Republican 08.11.1988 75 9 781 55 58 41 186 130 William J. Clinton Democrat 03.11.1992 88 13 899 76 73 41 222 131 William J. Clinton Democrat 05.11.1996 95 16 1012 91 82 42 346 148 George W. Bush Republican 07.11.2000 101 26 1107 107 73 48 352 227 George W. Bush Republican 02.11.2004 82 21 848 90 62 20 347 119 Barack H. Obama Democrat 04.11.2008 92 25 673 54 40 19 220 97 Note: This table provides summary statistics for each election covered by our analysis. In the first column, we list the U.S. presidents that were elected during our 1976 - 2008 sample period. For each president we document the respective political party (Republican or Democrat) and the election day. In addition, we document the number of companies in each of the outlined industry divisions included in the analysis of cumulative abnormal stock price returns following the election day. 22 Table 2 Industry cumulative abnormal returns following the election day Election Mining Construct. Manufact. 0.3 1.7 1.4 0.5 6.5 15.1 0.4 1.4 3.2 -0.5 -9.5 -12.7 -0.1 -0.8 -0.6 -0.9 -2.0 -1.6 0.6 0.8 0.1 0.9 2.7 3.7 0.2 0.4 -0.2 1.0 2.0 1.1 Transport. Wholesale Retail Financials Services -0.3 1.0 1.7 4.8 2.1 3.4 0.8 2.1 8.5 9.2 15.2 17.7 J.E. Carter 0 +2w +4w +10w +18w +26w ** ** ** -0.1 0.3 2.3 3.1 2.1 8.1 * -0.2 0.7 1.1 6.0 0.0 1.2 -0.2 3.9 4.6 0.7 -4.4 -11.5 1.2 1.1 1.9 1.0 3.1 7.9 -0.1 3.4 3.0 -2.5 -1.2 1.7 * *** ** ** * R.W. Reagan (1) 0 +2w +4w +10w +18w +26w -0.5 -2.3 -3.2 -6.2 -6.9 -13.2 *** * *** -0.3 1.0 -2.9 -4.2 -8.1 2.0 -0.2 -0.8 -2.4 -9.4 -5.5 -9.1 * *** * ** 0.7 0.6 0.6 -1.1 9.5 9.0 *** * *** *** 0.6 4.8 3.7 1.7 0.8 -2.4 ** * 0.0 -0.1 -0.3 -2.4 -4.4 -5.5 ** *** -1.1 -0.6 0.9 2.9 4.5 7.4 0.1 0.8 1.3 2.3 4.1 6.5 ** ** *** *** -0.5 -0.5 0.1 -3.5 4.4 -0.1 * 0.0 -0.3 -1.1 -2.6 -3.0 -2.9 ** *** *** *** 0.5 -0.1 0.0 0.5 -0.7 -1.7 ** ** ** 0.2 1.7 2.2 5.9 10.2 9.5 *** *** *** *** *** -0.4 2.1 5.5 14.0 17.6 25.4 0.2 0.7 0.9 2.7 8.0 6.7 ** ** *** *** *** -0.9 -0.9 -1.1 1.1 1.7 1.4 R.W. Reagan (2) 0 +2w +4w +10w +18w +26w * * ** -0.2 -1.6 -1.5 -0.2 -1.5 -2.9 -0.3 -0.4 -1.6 0.4 3.3 2.5 -0.3 0.2 -0.4 4.4 4.3 0.4 -0.4 -2.0 1.6 1.7 4.6 4.3 0.1 -4.5 -3.0 -1.4 2.9 0.6 * G.H.W. Bush 0 +2w +4w +10w +18w +26w -0.3 0.2 0.0 2.7 4.8 2.9 * 1.3 3.7 -0.1 -8.0 -8.4 -6.7 ** * 3.0 5.8 10.9 15.7 22.7 17.9 ** ** ** -0.1 -0.1 -0.5 0.9 0.5 0.8 * *** * ** * 0.0 0.1 1.0 -0.7 3.4 5.9 W.J. Clinton (1) 0 +2w +4w +10w +18w +26w -0.3 -0.8 1.3 3.1 11.9 25.7 *** *** ** ** ** 0.1 2.2 3.0 5.2 5.0 6.8 *** *** *** *** *** 1.0 4.7 9.2 13.9 16.6 22.0 *** *** *** 0.5 0.3 0.0 3.0 2.3 4.2 * *** *** *** *** *** -0.3 0.4 1.3 3.7 5.1 6.7 ** * -0.1 0.8 2.4 7.9 10.9 9.3 * * * ** W.J. Clinton (2) 0 +2w +4w +10w +18w +26w 0.3 2.2 1.3 9.3 5.6 7.9 ** *** ** * 0.2 -1.0 -2.9 11.2 12.0 10.7 * -0.1 0.2 0.6 3.5 5.9 6.3 -0.4 0.9 -0.1 1.0 2.1 1.2 0.8 3.8 2.4 8.3 12.2 11.3 1.0 -2.1 -3.2 4.2 11.1 15.2 -1.2 -8.0 -10.5 -5.4 3.4 -1.3 * * * ** G.W. Bush (1) 0 +2w +4w +10w +18w +26w 0.4 -5.5 -8.3 4.9 1.4 0.2 *** *** 0.4 -1.5 -3.8 1.4 6.7 12.4 -0.4 -1.7 -2.4 0.1 5.3 7.4 0.3 -2.9 -1.1 13.2 12.4 5.5 ** *** *** *** *** 1.0 0.8 -0.5 4.6 6.0 11.2 -0.1 1.7 2.4 4.9 4.4 2.8 *** *** *** *** *** 0.0 0.7 2.5 1.0 4.0 3.5 0.1 -5.4 -4.3 3.1 -5.0 16.8 *** *** ** *** *** -0.3 -2.1 -3.7 2.5 -10.0 27.3 ** * * *** *** *** ** *** *** 0.4 0.0 2.1 4.6 12.0 12.4 ** *** *** *** *** 0.8 -1.4 -4.0 5.3 9.0 10.5 *** *** *** *** G.W. Bush (2) 0 +2w +4w +10w +18w +26w 0.5 0.5 0.8 -0.6 5.8 0.5 0 +2w +4w +10w +18w +26w 1.3 -20.3 -17.2 11.1 15.7 66.0 * *** * * ** ** * -0.1 1.5 2.7 5.2 7.4 4.8 * ** ** *** 0.2 1.7 1.8 7.2 5.6 0.6 * -0.1 -0.1 1.1 1.2 -0.2 -0.5 ** -0.4 -0.5 -0.6 1.4 1.2 1.3 B.H. Obama * *** *** ** ** *** 1.5 -8.4 4.2 16.1 11.7 26.9 ** *** * *** 0.5 -7.9 -9.7 1.5 -7.7 14.8 ** ** ** -0.5 -0.6 0.8 -2.8 -14.0 -5.8 -0.8 2.6 4.4 4.3 1.5 -1.8 * *** ** 0.1 -4.9 -3.6 5.4 3.8 31.9 ** * *** Note: We report mean cumulative abnormal stock price returns for eight industries following the election day of the U.S. presidential elections between 1976 and 2008. The event windows are listed below each president and denoted as “0” (the day following the election), +2w (two weeks following the election), etc. All values represent percentage returns. The symbols ***, **, and * denote statistical significance at the one, five, and ten percent level, respectively. 23 Table 3 Sector performance based on the winning political party (all elections) Panel A: Elections won by a Democratic candidate Period 0 +2w +4w +10w Constant 0.005 0.033 ** 0.037 ** 0.061 Mining 0.003 -0.076 *** -0.066 *** 0.015 Contruction 0.013 -0.041 0.017 0.073 -0.001 -0.022 -0.019 Manufacturing Transportation +18w ** 0.087 ** +26w 0.043 0.045 0.248 0.064 0.098 -0.023 -0.037 0.011 * 0.003 -0.005 0.003 Wholesale -0.004 -0.029 -0.037 Financials -0.002 -0.001 Services -0.006 -0.025 ln(mcap) -0.001 -0.003 -0.003 leverage 0.000 0.000 0.000 net income / total assets 0.001 0.059 0.080 Adjusted R-squared 0.001 0.013 0.008 0.002 0.004 0.016 Prob(F-statistic) 0.195 <0.001 <0.001 0.038 <0.001 <0.001 ** *** 0.005 -0.020 0.082 -0.037 -0.053 -0.010 0.003 -0.019 0.004 -0.022 -0.012 0.009 0.018 0.107 ** 0.000 -0.005 * 0.005 ** 0.000 0.000 *** 0.000 * 0.076 0.044 * *** ** ** 0.043 Observations: 4,902 Panel B: Elections won by a Republican candidate Period Constant 0 +2w +4w +18w +26w -0.004 -0.036 -0.023 0.044 Mining 0.005 0.011 0.003 0.014 -0.018 -0.030 Contruction 0.009 0.019 0.014 0.046 0.023 0.048 Manufacturing 0.003 0.028 ** 0.030 ** 0.028 -0.002 0.019 Transportation 0.007 0.035 *** 0.038 ** 0.039 * 0.005 0.030 Wholesale 0.006 0.022 * 0.034 ** 0.044 ** 0.034 0.059 Financials 0.005 0.028 ** 0.042 *** 0.027 0.001 0.022 Services 0.006 0.022 * 0.018 ln(mcap) 0.000 0.001 ** 0.002 leverage 0.000 0.000 net income / total assets 0.012 0.083 Adjusted R-squared 0.000 Prob(F-statistic) 0.355 * ** * *** -0.043 +10w *** ** * 0.026 0.035 * 0.009 0.026 0.002 * -0.002 -0.002 0.000 0.000 0.040 0.091 0.005 0.005 0.001 0.001 0.001 <0.001 <0.001 0.072 0.044 0.044 *** 0.000 * 0.197 * 0.000 *** 0.154 * Observations: 6,305 Note: We report regression results with mean cumulative abnormal stock price returns following the election days of the U.S. presidential elections between 1976 and 2008 as dependent variables. The event windows are denoted as “0” (the day following the election), +2w (two weeks following the election), etc. The explanatory variables are as explained in the text. Panel A contains the sub-sample for the elections in 1976, 1992, 1996, and 2008 which were won by a Democratic candidate. Panel B contains the sub-sample for the elections in 1980, 1984, 1988, 2000 and 2004 which were won by a Republican candidate. The symbols ***, **, and * denote statistical significance at the one, five, and ten percent level, respectively. 24