LIFO Pranks - The Analyst's Accounting Observer

THE ANALYST'S

ACCOUNTING OBSERVER

Jack T. Ciesielski, CPA, CFA

______________________________________________________________________________ ________________

Volume 2, No. 4 May 5, 1993

LIFO Pranks: Soft White Underbelly Of A Conservative

Accounting Technique

The usual intent of companies using the LIFO inventory assumption is to lower income taxes and save cash during inflationary times. An additional benefit is that LIFO produces a more relevant cost of sales figure, and thus more relevant earnings. However, the LIFO costing assumption can also produce prankish results that aren't always noticed by financial statement users. Under certain circumstances, LIFO can inflate earnings as well as lower them vis-a-vis other inventory methods. Analysts and investors who aren't wise to the distortions that LIFO can produce in gross margins may develop forecasts and expectations that are based on a flawed understanding of the real economics in firms using this technique.

I. Dogma Versus Reality

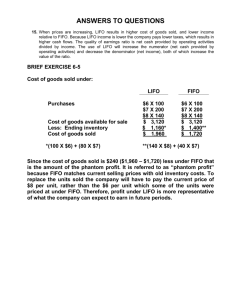

In their assessment of whether or not a firm's accounting practices are conservative, analysts usually hold the LIFO (last-in, firstout) inventory flow assumption in high regard. To see why, observe the brief comparison between LIFO and FIFO (first in, first out) accounting in Table 1 on the next page.

Table of Contents

Page

I.

Dogma Versus Reality . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

General Rules Aren't Always Right

II.

The Layer Liquidation Prank . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

Non-Recurring Credits Disguised As A Good Thing

III. The Deflation Prank . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

When LIFO Helps Income

IV. A Bigger Deflation Prank . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

When LIFO Really Helps Income

V.

Is There Life After LIFO? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8

There's No Such Thing As A Perfect Solution

Companies In This

Issue:

Acme Metals Inc.

Acme-Cleveland Corp.

Alcoa

Applied Power Inc.

Autoclave Engineers

Avery Dennison Corp.

Bearings, Inc.

Belding Heminway

Butler Manufacturing

Caterpillar, Inc.

Continued on back page

-2-

Table 1.

Comparison Of FIFO vs. LIFO Assumptions During An Inflationary Year.

FIFO—oldest merchandise sold first LIFO—newest merchandise sold first.

Sales

Cost of Sales:

Purchases:

100 @

600 @

800 @

100 @

1,000 @

1,500 @

1,500 @

$2

$4

$8

$10

$70,000 Sales

Cost of Sales:

Beginning inventory 1,600 @ $6.25

10,000 Beginning inventory 1,600 @ $6.25

10,000

$12 12,000 Purchases

$15 22,500

$18 27,000

71,500

100 @

600 @

800 @

100 @

1,000 @

1,500 @

1,500 @

$2

$4

$8

$10

$12

$15

$18

$70,000

12,000

22,500

27,000

71,500 Cost of goods for sale

Less ending inventory 1,600 @

Cost of goods sold

Gross profit

Cost of good for sale

$18 (28,800) Less ending inventory 1,600 @ $6.25 (10,000)

4,000 @$10.68 avg. 42,700 Cost of goods sold

$27,300 Gross profit

4,000 @$15.38 avg. 61,500

$8,500

Gross profit margin

Holding profit:

($18-$6.25) X 1,600 units

39% Gross profit margin

$18,800

12%

Admittedly, the example is heavy-handed — the price level of the merchandise increased 188% in one year – but it gets across the point. Using FIFO during an inflationary period produces higher income, because the oldest – thus, lowest-costed inventory gets matched against current revenues.

Presumably, the unit selling price is higher than it was when the inventory was purchased. That superior gross margin percentage of 39% is an illusion — it's due only to the inventory holding profit of

$18,800 higher than the beginning inventory, for the same number and kind of units. By holding inventory for a year, the company realizes a cashless profit of $11.75 per unit. FIFO provides false signals about the firm's future profitability — unless there's extremely rapid deflation, it won't be selling any items next year that it buys at an average price of $6.25.

Under FIFO, there is a perverse incentive to stockpile inventories as long as prices increase. This keeps building the chain of holding profits. Rather than controlling working capital, FIFO costing combined with inflationary thinking can induce a management to squander working capital.

In comparison, LIFO provides a more truthful depiction of current earnings — the current costs of sales get matched more closely with current revenues. LIFO doesn't perfectly compensate for inflationary effects — notice that there are items sold that had a $12 and $15 unit cost, and thus they don't completely represent current costs ($18 per unit). It's also true that LIFO understates balance sheet inventory figures immediately, but this is widely recognized. Compared with the benefit of saving income taxes in real cash terms, the trade-off between a flawed balance sheet for more cash taxes saved seems minor. In fact, during the 1980's takeover era, investors looking for the next acquisition target usually included LIFO "cushions" or "reserves" in their estimates of takeover value. Their estimate of

LIFO cushions represented the difference between recorded inventory values and current values, and was easily deduced from financial statement disclosures. No one complained about balance sheet amounts.

Thus, the dogma developed that LIFO is a more conservative accounting practice than other methods — and rightly so, when rising price levels affect a company's inventory. LIFO is often perceived by investors as a strict accounting technique that produces higher quality earnings than other inventory flow assumptions — a sort of protective shell for statement users, like the armor of an armadillo. Nevertheless, flip over an armadillo and you find a soft white underbelly. If one questions some of the assumptions that make LIFO appear attractive, its soft white underbelly is also revealed. Inflation hasn't been the same kind of animal it was in the

1970's when companies began to employ LIFO

-3accounting en masse. In fact, with the calming of inflation in the 1980's, and the adoption of "lean" inventory systems, LIFO produces some nettlesome quirks of its own. A properly skeptical analyst will analyze how a company's inventory accounting affects its caliber of earnings, and look for the pranks that LIFO can play on the unwary.

II. The Layer Liquidation Prank

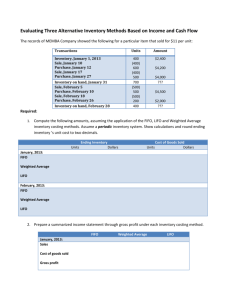

In the example provided earlier, suppose that this company implemented new inventory controls and found it unnecessary to make as many purchases in the current year to generate the same number of sales. That means that the last purchase of 1,500 units wouldn't occur, but the layers of inventory in the beginning balance would be liquidated — at the costs recorded in prior years. Under this scenario, the cost of goods sold would be $44,300:

Units Price Cost of Sales

1,500 @ $15 = $22,500

1,000 @ $12 = 12,000

100 @ $10 =

800 @

600 @

4,000

Gross profit

Gross profit margin

$8 =

1,000

6,400

$4 = 2,400

$44,300

$25,700

37%

However, the company has burned down its inventory levels and matched its prior year inventoried costs with current year revenues. Those three

"bites" out of inventory had a recorded cost of

$9,800, but had the company made purchases of those goods, it would have cost $18,000. The $8,200 difference between the two figures from the invasion of the inventory layers is called a LIFO liquidation, and it has the same effect on income as a FIFO holding gain: it's a mismatch of different period costs and revenues. It won't be realized in cash — the goods that created it may have already gone out the door. (Physical inventory flows do not necessarily match cost flow assumptions). The effect is the same, whether intentionally managed to this result by a company's managers, or if it occurs as an honest inventory control effort. Call it a LIFO liquidation, a LIFO layer invasion, or a LIFO credit: it amounts to a distortion of the cost of goods sold and gross margins. Compounding the problem is the fact that this is a non-recurring income booster — unless the company burns down more lower-costed inventory each succeeding year. There are limits to how far that can be done; at some point, the inventory level approaches zero.

Most analysts try to remove non-recurring items like asset sale gains and restructuring charges from net income in their evaluations of earnings. If the non-recurring charges aren't segregated on the income statement, analysts typically examine "other income and expense" for any unusual transactions.

However, LIFO liquidation credits lurk in the cost of sales and may go unnoticed by analysts. They then use existing gross profit margins as starting points for earnings estimates, without realizing that they may be inflated, and add their own inflation to boot. The results may be earnings estimates that are skewed to the high side, and disappointment when the company doesn't deliver.

To provide some real-world insights, Table

2 displays a sample of companies that experienced

LIFO liquidations in 1992. Columns (a) show the primary earnings per share before the cumulative effect of accounting changes for the companies, adjusted for non-recurring items like asset sale gains or losses and restructuring charges. Columns (b) show the per share LIFO liquidation credit, net of tax, and columns (c) show the difference between (a) and (b) — the earnings per share levelled for LIFO liquidation credits. Column (d) shows, in absolute percentage terms, what proportion of the original

EPS was really LIFO liquidation cre-dits. It's interesting to note that for Deere & Company and Twin

Disc, Inc.

, the LIFO credit was all of earnings per share and then some. Finally, columns (e) shows

-4the year-to-year earnings comparison based on original EPS and levelled EPS. The positive differences between the change rates show how much LIFO credits plumped 1992 earnings; negative differences show how the LIFO credits held back earnings comparisons.

Table 2.

Companies With 1992 LIFO Liquidation "Income".

(a) (b) (c)

Twin Disc, Inc.

Deere & Company

Net of tax

-Adj. EPSLIFO credit in EPS -Levelled EPS-

1992 1991 1992 1991 1992 1991

$0.37

($0.06) $0.46

$0.52

($0.09) ($0.58)

0.49

Outboard Marine Corporation 0.10

Federal-Mogul Corporation

Acme-Cleveland Corporation

0.61

0.81

Belding Heminway Co. Inc.

Autoclave Engineers, Inc.

1.19

0.36

TRINOVA Corporation 0.51

Aluminum Company of America 2.40

Butler Manufacturing Co.

0.48

Avery Dennison Corporation

Instron Corporation

Acme Metals Incorporated

Applied Power Inc.

General Motors

1.33

0.53

0.92

1.02

0.88

(0.32) (0.57)

1.08

(2.86) (6.34)

Interlake Corporation

Caterpillar, Inc.

Starrett (L.S.) Inc.

United Industrial Corporation

USX U.S. Steel Group

General Signal Corporation

Clark Equipment Company

Perry Drug Stores, Inc.

1.52

0.52

0.75

1.31

(2.72)

(0.05)

0.44

1.11

(0.12)

(0.98)

3.27

(1.82)

(0.84) (1.31)

(2.16) (1.35)

1.74

0.77

(4.80) (4.70)

3.45

3.32

(1.60) (3.04)

0.59

0.56

0.08

0.31

0.39

0.39

0.11

0.14

0.58

0.09

0.18

0.07

0.04

0.10

0.28

0.08

0.20

0.12

0.04

0.28

0.20

0.07

0.03

1.10

0.68

0.60

0.04

--

0.13

0.13

--

0.28

0.14

0.08

0.07

--

--

0.29

0.15

0.12

0.05

0.47

0.23

(0.07)

0.02

0.30

0.42

0.80

0.25

0.37

1.82

0.39

1.15

0.46

(0.36)

0.82

(3.14)

(0.92)

(2.36)

1.40

0.48

(5.08)

3.25

0.08

(1.67)

0.27

0.72

0.88

0.80

(0.64)

1.08

(6.34)

(1.60)

(1.50)

1.62

0.72

(5.17)

0.21

(3.40)

(0.65)

0.40

1.11

(0.25)

(1.11)

3.27

(2.10)

3.09

(3.12)

0.32

(d)

13.5%

13.2%

12.5%

10.9%

9.8%

9.5%

9.3%

7.9%

7.7%

5.8%

5.8%

4.4%

4.0%

% of EPS

1992

124.3%

114.3%

80.0%

50.8%

48.1%

32.8%

30.6%

27.5%

24.2%

18.8%

(e)

1992

------EPS Change------

Original Revised Diff.

NM NM NM

-62.6% -133.3% 70.7%

NM

NM

84.1%

NM

NM

NM

NM

5.0% 79.1%

7.2% -27.9% 35.1%

NM

NM

NM

NM

NM

-26.6% -44.3% 17.7%

NM NM

NM

NM

30.4% 30.7% -0.3%

-39.8% -42.5%

43.9%

-14.8%

54.9%

43.7%

-24.1%

50.5%

2.7%

0.2%

9.3%

4.4%

35.9% 42.5% -6.6%

-60.0% -57.3% -2.7%

-12.6% -13.6%

-32.5% -33.3%

-2.1%

1.0%

0.8%

1.7% -3.8%

3.9%

47.4%

5.2% -1.3%

46.5% 0.9%

27.1% 125.0% -97.9%

While not an exhaustive list, Table 2 does provide a reminder that significant LIFO liquidations do exist in the investment universe and can have real bottom line impacts. What an investor thinks he or she is paying for is not always what is received.

When this kind of exercise is performed, postponed investment decisions might result if the normalized earnings don't meet expectations. Table

3 shows the inflating effect of the LIFO liquidations on the gross margins of these companies, a reminder that the bottom line isn't the only thing to be distorted. As mentioned before, analysts who base earnings forecasts on historical margins could be rudely surprised if the historical margins have nonrecurring fluff in them.

-5-

Table 3.

LIFO Liquidation Effects On Gross Profit Margins.

Twin Disc, Inc.

Deere & Company

Outboard Marine Corporation

Federal-Mogul Corporation

Acme-Cleveland Corporation

Belding Heminway Company Inc.

Autoclave Engineers, Inc.

TRINOVA Corporation

Aluminum Company of America

Butler Manufacturing Co.

Avery Dennison Corporation

Instron Corporation

Acme Metals Incorporated

Applied Power Inc.

General Motors

Interlake Corporation

Caterpillar, Inc.

Starrett (L.S.) Inc.

United Industrial Corporation

USX U.S. Steel Group

General Signal Corporation

Clark Equipment Company

Perry Drug Stores, Inc.

32.0%

43.3%

11.4%

37.6%

7.3%

25.5%

14.2%

29.9%

24.8%

3.5%

27.8%

17.3%

26.7%

1992

---------------Gross Margin---------------

Stated Revised Diff.

18.0%

14.3%

23.3%

16.6%

24.5%

34.6%

35.0%

22.9%

22.7%

16.5%

16.6%

13.2%

23.0%

15.7%

22.2%

33.8%

34.1%

22.5%

21.9%

16.4%

1.4%

1.1%

0.3%

0.9%

2.3%

0.8%

0.9%

0.4%

0.8%

0.1%

31.3%

42.7%

11.3%

37.0%

7.0%

25.2%

13.9%

29.2%

24.4%

3.0%

27.4%

17.1%

26.6%

0.7%

0.6%

0.1%

0.6%

0.3%

0.3%

0.3%

0.7%

0.4%

0.5%

0.4%

0.2%

0.1%

Companies that experience current year

LIFO liquidations aren't the only ones that have distortion in earnings comparisons; it only takes liquidations in one year to ruin comparability with another that doesn't contain them. Table 4 presents essentially the same information as in Table 2, but for companies with 1991 LIFO liquidations and none in 1992.

-6-

Table 4.

Adjusted EPS Comparisons For Companies With 1991 LIFO Liquidations.

Culbro Corporation

Bearings, Inc.

Union Carbide Corporation

Younkers, Inc.

Louisiana-Pacific Corp.

Tektronix, Inc.

Wolverine World Wide, Inc.

Graco, Inc.

United Stationers

Textron, Inc.

Net of tax

-Adj. EPSLIFO credit in EPS -Levelled EPS% of EPS

1992 1991 1992 1991 1992 1991 1991

1992

-----EPS Change-----

Original Revised Diff.

$0.83 $1.15

0.49

0.61

0.70

0.20

3.11

1.27

3.26

1.03

1.04

1.65

0.96

1.61

1.46

1.18

0.92

0.64

3.66

3.42

--

--

--

--

--

$2.45

1.12

0.06

0.15

0.09

-0.13

-0.11

-0.08

-0.04

-0.15

$0.83 ($1.30)

0.49

0.70

3.11

3.26

1.04

1.52

0.96

1.50

1.46

1.10

0.92

0.60

3.66

(0.51)

0.14

1.12

0.94

3.27

213.0%

183.6%

30.0%

11.8%

8.7%

7.9%

6.8%

6.8%

5.8%

4.4%

NM

NM

250.0%

144.9%

216.5%

NM

NM

NM

NM

400.0% -150.0%

177.7% -32.8%

246.8% -30.3%

-37.0% -31.6% -5.4%

-40.4% -36.0% -4.4%

23.7% 32.7% -9.0%

44.8% 53.6% -8.8%

7.0% 11.9% -4.9%

III. The Deflation Prank

The dogma is that LIFO produces more conservative earnings that FIFO during periods of inflation and this is certainly true. However, one must always take into account changes in the operating environment — and ask "What does LIFO do to earnings during deflationary periods?" I n m o s t cases, nothing. LIFO does what it's supposed to do, matching current costs with current revenues.

Though dogma holds that LIFO is more realistic in an inflationary setting, the same can hold true in a deflationary setting. FIFO may actually produce lower earnings results, but that doesn't necessarily mean that these results are more realistic.

Consider the case of Reynolds Metals , an aluminum company. The average price per pound of aluminum ingot has decreased from $0.74 in 1990 to

$0.58 in 1992. Application of LIFO accounting puts those lower prices into Reynolds' cost of sales. If

FIFO accounting had been used, cost of sales would have been $21.8 million higher in

1992 and $55.7 million higher in 1991. The lower cost of sales had nothing to do with layer liquidations as one might initially suspect; it was merely reflecting the real-world conditions of lower aluminum prices. (However, layer liquidation credits could still occur.)

The threat to analyst/investor expectations in this kind of scenario is not that stated profit margins are deceiving, as in the case of layer liquidations.

Instead, if prices of the inventoried materials rise again suddenly, past margins won't be much of a guide at all to future margins. Higher costs would be shown immediately in cost of sales, while the speed at which they could be passed on to customers depends on the pricing prowess of the company.

Table 5 lists some companies that showed higher income in 1992 by using LIFO instead of

FIFO.

Table 5.

Companies With Higher Earnings Due To LIFO, Opposed To FIFO.

Adjusted EPS

1992 1991

Net of tax

LIFO effect in EPS

1992 1991

Thomaston Mills Inc.

Reynolds Metals Company

Vulcan Materials

$2.17

(0.74)

2.41

--

2.60

1.64

$0.16

0.22

0.17

--

0.61

(0.10)

% EPS

---Due to LIFO---

1992 1991

7.4%

29.7%

7.1%

NM

23.5%

6.1%

-7-

IV. A Bigger Deflation Prank

LIFO states the cost of sales just fine during deflationary periods as long as the beginning and ending inventory values are in line with current costs.

However, when current prices drop drastically from the inventoried values, LIFO can produce the bizarre effect of introducing holding profits in income.

First Brands Corporation illustrates this situation nicely. First Brands, being a leveraged buyout of some Union Carbide consumer products businesses, capitalized market values in LIFO-costed inventory at the time of the LBO. Since that time, the price of materials has decreased markedly and so has the current manufacturing cost of inventories.

Observe the following income statement information excerpted from First Brands 1992 and 1991 annual reports:

($in millions) 1992 1991 1990

Sales $988.5

$1,073.0

$199.7

$1,086.6

$208.5

Cost of purchases &

mfd. goods 599.5

Goods available

for sale 791.3

Ending inventory 203.2

Cost of sales 588.1

662.7

862.4

191.8

670.6

645.2

853.7

199.7

654.0

Gross profit $400.4

Gross profit margin 40.5%

$402.4

37.5%

$432.6

39.8%

Replacement cost of inventories, whether measured by FIFO or some other means, is a required disclosure for companies using LIFO. Substituting these inventory values from the First

Brands annual reports into the calculation of cost of sales purges any "holding profits" due to price declines in inventoried goods:

($in millions) 1992 1991 1990

Sales $988.5

$1,073.0

$193.0

$1,086.6

$208.5

Cost of purchases &

mfd. goods 599.5

Goods available

for sale 774.0

Ending inventory 177.5

Cost of sales

Gross profit

596.5

$392.0

Gross profit margin 39.7%

662.7

855.7

174.5

681.2

$391.8

36.5%

645.2

853.7

193.0

660.7

$425.9

39.2%

Within gross profit, there are $8.4, $10.6 and

$6.7 million of holding profits in 1992, 1991 and

1990, respectively. Note that just because there is a deflation holding profit in income, the inventories are not deceptively overstated from a realization standpoint. Inventories must be stated at the lower the minimum value for market is defined as the net realizable value (sales value less costs of completion and disposal) less a normal profit margin. In the case of First Brands, the minimum market value (or floor) must exceed cost, or a writedown would be necessary. However, the above exercise shows that the earnings caliber of all LIFO-using companies is not equal — LIFO can create the same situation it was

-8intended to cure. In fact, if a company in First

Brands' situation were to liquidate inventory layers,

LIFO liquidation expense would result. When companies with lower current costs than recorded inventory costs are un-der investment consideration, it behooves analysts to pay plenty of attention to

Table 6.

Companies With LIFO Holding Profits.

inventory transactions — there are opportunities for unusual surprises.

Table 6 shows the effects of holding profits of earnings and margins for First Brands and also

Lafarge Corporation in 1992.

First Brands

Lafarge Corporation

Adjusted

EPS

1992

$2.02

(0.63)

Holding Profit

Margin Increase

1992

0.8%

0.4%

Net Holding Profit

Per Share

1992

$0.23

0.07

1991

$0.30

(0.01)

EPS

Boost

1992

12.8%

10.0%

V. Is There Life After LIFO?

None of the above is meant to suggest that

LIFO-costing is a patently deceptive accounting method — or that companies that employ it are intentionally misleading investors. The intention here is to challenge dogma — "LIFO produces higher quality earnings than other inventory methods" — and get analysts thinking about potential earnings pitfalls lurking in the bowels of corporate inventories

Due to limitations of any inventory accounting system, analysts should be alert to how changes in economic environments effect the bottom line.

Companies can't constantly change inventory assumptions back and forth because of a few years of low inflation or high inflation — how credible could results be? However, analysts and investors can always assess reported results with a critical eye.

Companies in this Issue

(Continued)

Clark Equipment Company

Culbro Corporation

Deere & Company

Federal-Mogul Corp.

First Brands Corporation

General Motors

General Signal Corp.

Graco, Inc.

Instron Corporation

Interlake Corp.

Lafarge Corporation

Louisiana-Pacific Corp.

Outboard Marine Corp.

Perry Drug Stores, Inc.

Reynolds Metals

Starrett (L.S.) Inc.

Tektronix, Inc.

Textron

Thomaston Mills Inc.

TRINOVA Corporation

Twin Disc, Inc.

Union Carbide Corporation

United Industrial Corporation

USX U.S. Steel Corp.

Vulcan Materials

Wolverine World Wide, Inc.

Younkers, Inc.

R.G. Associates, Inc.

The Fidelity Building

210 N. Charles Street, Suite 1325

Baltimore, MD 21201

Phone: (410) 783-0672

Fax: (410) 783-0687

Internet: jciesielski@accountingobserver.com

Website: www.accountingobserver.com

NOTE:

R.G. Associates, Inc. is registered as an investment adviser with the State of Maryland. No principals or employees of R.G.

Associates, Inc. have performed auditing or review engagement procedures to the financial statements of any of the companies mentioned in the report. Neither R.G. Associates, Inc., nor its principals and employees, are engaged in the practice of public accountancy nor have they acted as independent certified public accountant for any company which is mentioned herein.

These reports are based on sources which are believed to be reliable, including publicly available documents filed with the

SEC. However, no assurance is provided that the information is complete and accurate nor is assurance provided that any errors discovered later will be corrected.

Nothing in this report is to be interpreted as a “buy” or “sell” recommendation. The information herein is provided to users for assistance in making their own investment decisions.

R.G. Associates, Inc., and/or its principals and employees thereof may have positions in securities referred to herein and may make purchases or sales thereof while this report is in circulation.