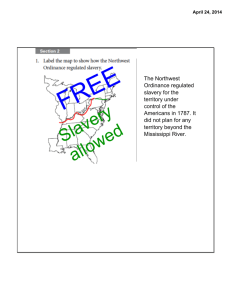

Lame Duck Logic

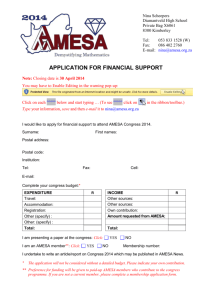

advertisement