Strategy Tips for Pax Romana

advertisement

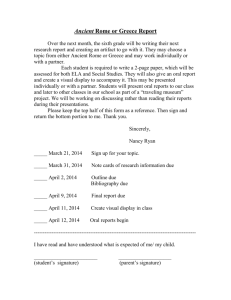

Strategy Tips for Pax Romana By Michael Gouker turn 3 of a 5 turn game makes little economic For those of you who are not aware, I openly admit to my obsession for Pax Romana (PR). What do I mean by this? Let me start by rationalizing a little. I constantly play PR, but it's really not my fault. I just happen to be where the game is being played. I also spend a great deal of time thinking about new strategies for PR. In addition, I'm watching other games of PR being played, but that's because I am moderating those games. Also, I check daily the latest posts regarding PR on Consimworld and Boardgamegeek, but there is nothing peculiar about any of this — is there? As Bob Dylan says, "Let me do what I want to do, I can recite them all." Now that I have hopefully disabused you about any questions regarding my sanity, let me discuss this glorious game. Most of my discussion will center on the multiplayer game, because although I enjoy the 2-player scenarios, the dynamics of the multiplayer game, and the psychology involved, is what most intrigues me. In this regard, PR has a lot in common with games like Civilization and Diplomacy, where the interactions among the players are the most challenging element. At the same time, however, PR incorporates a first-class combat system and a system of random events (via the cards) that rewards the great improviser. Let me say a few words about the importance of diplomacy in PR. First, you can definitely win PR all by yourself — if everything goes right for you. If you can avoid the bloody attrition wars, if you can build-up your empire without the other players noticing, and if you can get a couple of lucky Opportunity Objectives, you can win. Frankly, I think this is extremely improbable, especially if you are sitting with players worth their salt (and most players are!) Therefore, you will need to have allies along the way. The most important thing about being good at diplomacy is being trustworthy. If you are not trustworthy, then no one will ever make alliances with you. If nobody makes alliances with you, then you can never backstab them in the nick of time to win the game. I'm only kidding! I would never, ever, backstab another player. I really don't care about winning the game. Some people find my attitude hard to believe, but I find the sheer joy of playing PR rewarding enough. I've won the game before, I'm quite satisfied. Why malign my good reputation by an unworthy slice of betrayal? So, aside from recognizing the importance of diplomacy in PR and the risks of backstabbing, how else can you win? One way is to get a good sense of the overall game early. Every game of PR plays out differently. Some are low-scoring contests, with bloody struggles from the first activation where the last man standing is the winner. Some are gradually building affairs where the scores are higher, and you get to pull out those sweet 10 HI counters. Yet, most games of PR are somewhere in between. Different types of game strategies can favor different PR powers. It is not a hard and fast rule, but I have seen Carthage players win a lot of low-scoring games, while Roman players tend to prefer to have a peaceful borders (a live-and-letlive) strategy, until the republic recruits 10 shiny new legions to enforce its version of pax (peace). Greece has reasons for passing the peace pipe too, because their border is porous and their stability is low. As a player, you need to know when and how to strike. The answers are not only in the opportunities and rewards that you have at your disposal, but you also need to watch what the other players are doing. My strategy is to always assume that there is a state of war between my power and those next door. That does not mean that war should be pursued vigorously. It all depends upon what the other players are doing. If I am the East, and I am fighting Greece relentlessly, while Rome and Carthage build, I know I will lose the game. War is very expensive. The true cost is not only in what you lose, but what others are gaining while you are at war. You can also view Pax Romana as an economic enterprise. Beyond a doubt, there is a finite amount of money in PR. The other commodity that is valuable is a player's activations. Think about it this way: in a 5-turn game, you have about 20 activations. The East might have fewer due to the Successor Wars. You can also get a free activation from a Stability and Opportunity card. Twenty activations are not very many. This limits what you can do. For example, you need a minor move to build a town and another to build a city — you spend 2 activations for every city. Think about the income generated by a city. A city costs 5 Talents (2T for the town and 3 T more to change it into a city), 1 garrison, and 1 HI to build. Price the garrison at 1/2 Talent, because players usually build LI just to make garrisons, and they breakdown into 2 garrisons for a movement point. The HI costs 2 T, so a city costs 7.5 T total. A city's income is 3 Tper turn, so it will take 3-turns for a city to become profitable. Therefore, building a city in sense. How much should you pay to take a city? Obviously, from a strict economic point of view the cost should not exceed the return. But wait a minute! Your opponent gaining income also works against you in future armies that might oppose you. It might be worth taking anyway. In short, the value depends on the type of game strategy you are employing. There are intangibles too. City walls can help protect your empire. But, the downside to this kind of strategy is that if you build cities as an outer-ring of protection, your enemies may choose to take your cities, and thus create income for themselves. It can behoove you to build as far away from your front lines as possible. This works especially well for the East and Carthage. Rome building cities in Germania is also a smart tactic. I have never seen cities in Britannia, but it would be a great place, but the bottomline is you must keep your supply lines open to your cities. No matter what type of overall game strategy you choose to employ in PR, I think it wise not to attempt to be the leader too early. You need to build-up your empire into a true power with the potential for winning. The real art here is choosing when to make your move and being prepared for the reactions from the other players. Sometimes you can accidentally become the leader early on, and thus be targeted. If you can convince the other players that this was not your intention, you won't need any more advice from me about diplomacy! Games where there is a variable ending are a lot trickier in this respect, because there is a huge incentive to push forward and grab the brass ring. You can try to calculate the odds of the game ending, but a better rule is don't trust your calculations. Inevitably, the worst will happen, and you will lose by being too conservative. Concentrate more on building a strong civilization with good armies and seize victory when you are strong enough to fight back. How do you do that if you start out as a weakling? There is always a way. Take Rome (pun intended - sorry). At the beginning of the game, Rome has two provinces and doesn't even control its own territory. The solution here is to score enough civilization points to get a victory point. Rome should build towns and cities. Even if you score only one victory point in the first turn, you are definitely in the game. By turn four, you might be punishing the others with legions and scoring 10 VP or more and they will be happy scoring only a few themselves, but you will need that 1 VP anyway. PR games are usually close scoring affairs. Therefore, score every turn, no matter what. Strategy Tips for Pax Romana Watching the score is vitally important. The game has so many layers that you can forget what is most important. The winner is not the player who has the most cities or the player who conquers the other players. The winning player is the one with the most VPs. You score your VPs over the course of the entire game. Also, your score is relative to the other players' performance. This means that sometimes it is a terrible idea to crush your opponent, because making him too weak will help another player score more points than you. This complexity is sometimes mind-boggling. In this situation, I play intuitively. If my successes against one neighbor leaves them vulnerable to an opponent, I wait for the sword to fall, and then cut a deal, maybe allowing the two of them to fight while I build, or take on my other neighbor. Before going into some specifics about the various sides, I want to briefly address the criticism about randomness or bad luck. I can truthfully say you make your own luck in PR. First of all, just assume all the cards in PR are bad news. In most games, it is fun or exciting to draw a new card. In PR, with each card draw, assume you are putting your finger in a mousetrap. The cards will look better if you are expecting something bad. You will be surprised at how this philosophy changes your perspective. Another thing, bad cards (like Barbarian Invasions) in the hands of a clever player can be most gratifying. I just love watching Greece's stability fall to -4 because of a drought. (Oh please let's have a stability check now!!!) The same holds true for your leader draws. I have used 0-0 leaders to do great things, so what is the problem with the 1-4 fellows? Yes, it would be nice to get a 4-5 elite leader every so often (along with a Conqueror and Stability and Opportunity card on the side), but elite leaders are rare. If you are happy to draw a 2-4, then when the elite guys appear you will really be thrilled. You will probably roll "1"s on their movement rolls though, so do not get too enthusiastic. Pessimism is your friend. If you imagine the worst possible outcome, most of the time, your luck will surprise you. If not, the problem is not your luck, it is your imagination. Lastly, Pax Romana is a very balanced game. Everybody gets at least one turn in the barrel and usually more. The trick is to make yours as painless as possible — playing possum might work once or twice — while making certain that the player just ahead of you has the worst time of anyone. Also, remember that if you look like you are overwhelmed by adversity, you can save up money and forces and wait for the affliction to pass. Note to Roman players — Pyrrhus is an affliction. You do not have to defeat him, he will go away. It seems I'm already getting into the specifics, so let's talk a little more about Rome. During the game, Rome typically evolves from a doormat into a thundering locomotive. It takes some time. Rome has a hard time winning short games, but I have seen it done. The Roman player must be patient and concentrate on building his armies and his civilization before plunging head-first into the conflict. Also, Rome needs fleets desperately and it has none at the beginning of the game. The decisive point of Rome's game is in the Sicilies, and Rome's mortal enemy is Carthage. It is in Carthage's interest to force Rome into an arms race, because Rome escalating in the Sicilies allows Carthage to move into Hispania and delays Roman expansion. Rome has to also be concerned with Greece, though Greece has enough problems with the East. Usually Rome and Greece reach some kind of understanding about Bruttium and Tarentum, but I generally think that is a mistake. I always suspect that it is better to fight a low intensity war and lose the territory thus making my opponent lose enough forces to make him think twice about fighting again. I have seen a lot of success (short-term success, mind you!) with Bruttium arrangements, but usually one side gets burned and regrets the deal later. While Greece has a toehold in Italy, Rome needs to be careful. Once that toehold is gone, what leverage is there? Greece's fortune is intrinsically linked to the East's performance, but it is Greece's responsibility to make the East pay dearly for every space in Asia Minor. Ideally, Greece will be on the offensive against the East throughout most of the game. The key to taking the East apart is control of Cyprus. Greece can grab the island early on by investing a major move to go there while bringing its galleys back from the East colonies in Sidon and Tyre. If Greece can set up a city or town in Cyprus, the East will have a very hard game. The Greek player worries a lot about stability. I think there is reason for concern, but I do not believe that the problem is any worse than the Barbarian Invasions for Rome, the strength limitations for Carthage, or the Successor Wars for the East. It is just a variable to be factored into your play. Should you avoid turmoil? Well, naturally, but you have to play your game strategy first. If you need to make a risky play that might give you a chance at victory, but might cost you your home province if you fail, most of the time you should probably take the chance. If you are that close to victory, you will have a difficult time getting that close again. Furthermore, stability is a relative quantity. Both Greece and the East can pull the Black Sea Gambit. This is the act of grabbing Scythia, Sarmathia, and the Chersonese, which are all good for income and are also nice places to build cities that can be easily defended. The East can add Armenia and a couple eastern provinces of Asia Minor and have a good size block of control and income. Naturally, neither Greece nor the East should allow the other to perform this move, but usually the first player that tries the Black Sea Gambit will pull it off and hold it for the whole game if that player remembers to build a couple fleets. There are other important targets for the East. I think Crete is a great place to move (assuming this is not one of the games where you are fighting to hold Cyprus from Greece!) and if you pay Rhodes a Talent, it is pretty easy to get there. If you are in Crete, the belly of Greece is wide open. I mentioned earlier the importance of Rome's winning the war in the Sicilies against Carthage. There is no reason for a good Carthage player to lose this war. You have no other enemies. Moreover, Carthage has a significant advantage in fleets. Carthage should use their fleets to guard the islands in the first turn while Pyrrhus is likely rampaging around Italia. My first priority as Carthage is to keep what I have and build cities and towns before moving into Hispania. Eventually, Hispania is a great place to go, especially if Rome's attentions are diverted, but going there too quickly will drain all your resources and leave you vulnerable to a war against Rome that you will be doomed to lose. The Carthage player must be patient, and never give up a fleet. Once Carthage is strong enough — for example, you see Rome busy with Greece; the East busy with Greece — don't forget to look towards the East yourself. Just because the East is not likely to pound on your door does not mean you can't pound on their door. Maybe you strike at the East as a favor to Greece, in exchange for a strike by Greece against Rome? I hope you can now see some of the many layers within the game design of Pax Romana. Before signing off, I want to thank designer Richard Berg and developer Neil Randall for this incredible game. I also want to thank my worthy opponents, and all the players in the games I have moderated. I've learned to play PR well thanks to all of you. As I'm teaching others the game, I'm learning more about PR myself. Thanks also to GMT Games and C3i Magazine for giving me this opportunity to share my love for PR with all of you. Finally, I want to say to all my future opponents that I am looking forward to crushing you slowly and mercilessly, though I will do my best to honor all trivial agreements in the meantime.