The Bisexuality Report

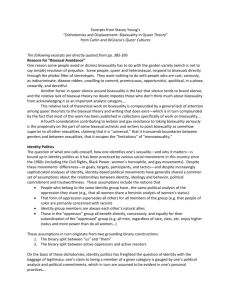

advertisement