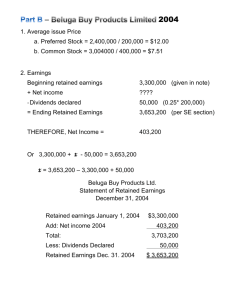

Dividend Policy, Strategy and Analysis

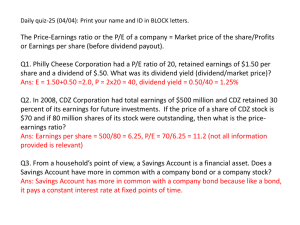

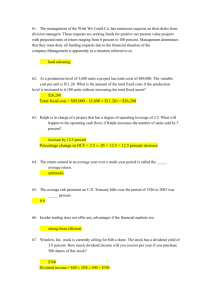

advertisement