Article #1

advertisement

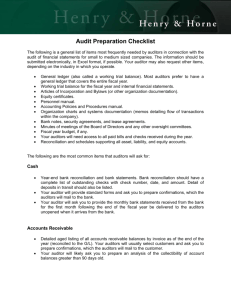

ACCOUNTING HORIZONS Supplement 2003 pp. 1–16 Does Big 6 Auditor Industry Expertise Constrain Earnings Management? Gopal V. Krishnan SYNOPSIS: Earnings management remains a popular topic of debate and discussion among investors, regulators, analysts, and the public. One mechanism that might mitigate earnings management is auditors’ industry expertise. Using a large sample of clients of Big 6 auditors, this research examines the association between auditor industry expertise, measured in terms of both auditor market share in an industry and an industry’s share in the auditor’s portfolio of client industries, and a client’s level of absolute discretionary accruals, a common proxy for earnings management. Clients of nonspecialist auditors report absolute discretionary accruals that are, on average, 1.2 percent of total assets higher than the discretionary accruals reported by clients of specialist auditors. This finding is consistent with the notion that specialist auditors mitigate accruals-based earnings management more than nonspecialist auditors and, therefore, influence the quality of earnings. Keywords: industry specialization; Big 6; specialist firms; earnings management; discretionary accruals; audit quality. Data Availability: The data used in this study are publicly available from the sources indicated in the text. INTRODUCTION arnings management is a concern for investors, regulators, analysts, and the public. In a review of the earnings management literature, Healy and Wahlen (1999) call for research on factors that limit earnings management. This study is a response that provides empirical evidence on one mitigating factor: auditors’ industry expertise. Specifically, I examine the association between Big 6 auditor industry expertise and the level of firms’ absolute discretionary accruals—a common proxy for earnings management. Bonner and Lewis (1990) find that, on average, more experienced auditors outperform less experienced auditors. Similarly, Bedard and Biggs (1991) observe that auditors with more manufacturing experience are better able to identify errors in a manufacturing client’s data than auditors with less manufacturing experience. This is consistent with the findings of Johnson et al. (1991) that industry experience is associated with enhanced ability to detect fraud. Wright and Wright (1997) conclude that significant experience in the retailing industry enhances hypothesis generation in identifying material errors. E Gopal V. Krishnan is an Associate Professor at the City University of Hong Kong. I appreciate helpful comments from Patricia Dechow, James Largay, and two anonymous reviewers. 1 2 Krishnan Specialist auditors are likely to invest more in staff recruitment and training, information technology, and state-of-the art audit technologies than nonspecialist auditors (Dopuch and Simunic 1982). Solomon et al. (1999) find that specialist auditors have more accurate nonerror frequency knowledge than nonspecialists. This finding is important because it is not unusual that client firms suggest nonerror explanations for ratio fluctuations. Audit effectiveness thus depends on the accuracy of auditors’ nonerror frequency knowledge. All these findings support the conclusion that auditors’ industry-specific knowledge is associated with audit effectiveness. How does an auditor’s specialized industry knowledge help in detecting earnings management? Maletta and Wright (1996) observe fundamental differences in error characteristics and methods of detection across industries. This suggests that auditors who have a more comprehensive understanding of an industry’s characteristics and trends will be more effective in auditing than auditors without such industry knowledge. Auditors who specialize in the banking industry can assess the adequacy of loan loss provisions better than nonspecialist auditors and, therefore, can improve the credibility of reported earnings. Auditors with expertise in manufacturing can evaluate whether the client’s provision for warranty obligations is in line with industry standards better than an auditor without this expertise. Specialist auditors are also likely to develop databases detailing industry-specific best practices, industryspecific risks and errors, and unusual transactions, all of which serve to enhance overall audit effectiveness. Besides having the resources and the expertise to detect earnings management, specialist auditors who enjoy a brand-name reputation have particular incentives to deter and report questionable or aggressive accounting practices. It has been accepted that Big 6 auditors are of higher quality than non-Big 6 auditors (DeAngelo 1981).1 Given their larger client base, Big 6 auditors have more to lose than non-Big 6 auditors in the event of a loss of reputation. Thus, Big 6 auditors should have more incentive to protect their reputation than non-Big 6 auditors. MacDonald (1997), for example, reports that between 1994 and 1997, Big 6 auditors dropped 275 publicly traded audit clients because of concerns about harm to their reputations or litigation risk. In short, Big 6 auditors who are also specialist auditors have both the expertise to detect earnings management and the incentives to report it. This argument is consistent with the findings of O’Keefe et al. (1994) that specialist auditors exhibit greater compliance with auditing standards (GAAS) than nonspecialist auditors. RESEARCH QUESTION AND CONTRIBUTIONS Taken together, findings of the above studies support the notion that specialist auditors have the resources, the industry-specific expertise, and the incentives to detect and constrain earnings management, and therefore enhance the quality of earnings. This leads to the research question: RQ: The absolute value of discretionary accruals of firms audited by specialist auditors is lower than the absolute value of discretionary accruals of firms audited by nonspecialist auditors. Consistent with prior research, I use the absolute value of discretionary accruals to proxy for accruals-based earnings management (Francis et al. 1999). The sample consists of 4,422 firms audited by Big 6 auditors from 1989 through 1998. I focus on clients of Big 6 auditors because they audit more than 80 percent of firms in the Compustat database. Confining the sample firms to those audited by the Big 6 makes it possible to isolate differences due to industry expertise rather than differences in audit quality between Big 6 auditors and other auditors. 1 Consistent with the prior research, I refer to the original Big 8 auditors (Big 5 after 1998 and now Big 4) as Big 6 auditors. Accounting Horizons, Supplement 2003 Does Big 6 Auditor Industry Expertise Constrain Earnings Management? 3 Using sales as a measure of client size, I estimate auditors’ industry expertise using two common proxies: the audit fees an auditor earns in an industry relative to the total audit fees earned by all auditors serving that particular industry, and an auditor’s audit fees earned from an industry relative to fees earned from clients across all industries served (Gramling and Stone 2001). I find that the clients of nonspecialist auditors report higher absolute discretionary accruals than the clients of specialist auditors. This finding is consistent with the notion that auditors’ industry expertise moderates earnings management. My study contributes to two aspects of the literature. The first is the literature on audit quality. My contribution is to demonstrate that audit quality varies even among Big 6 auditors. Research like Becker et al. (1998) tends to focus on audit-quality differences between Big 6 and non-Big 6 auditors and implicitly treats the Big 6 auditors as a homogeneous group in terms of audit quality. My extension treats auditor industry expertise as a dimension of audit quality. Second is the literature on auditors’ industry specialization. Here I contribute by providing an empirical link between auditors’ industry expertise and audit quality. In their review of audit firm industry expertise literature, Gramling and Stone (2001) observe that there is limited examination of whether industry specialization is associated with audit quality. They see the dearth of research as surprising, given the importance that client firms and audit standards setters place on industry expertise. My findings suggest that one reason specialty auditors charge a premium over nonspecialty auditors is because they are able to constrain accruals-based earnings management better than nonspecialty auditors and thus add credibility to the quality of reported earnings. SAMPLE SELECTION AND MEASURES OF AUDITORS’ INDUSTRY EXPERTISE I searched the 2000 version of Compustat PC Plus to identify the sample firms and their auditors. My sample period covers a ten-year period from 1989 through 1998. The selection criteria are as follows. I exclude financial institutions (SICs between 6000 and 6999) because auditor information for these firms is unavailable on Compustat. I also eliminate firms that changed fiscal year-ends during the period of analysis. As previously stated, I restrict my sample to firms audited by the Big 6 auditors. This sample selection procedure yields 24,114 firm-year observations representing 4,422 firms. Yearly firm-year observations are 1,481, 1,746, 1,806, 1,857, 2,046, 2,302, 2,624, 3,009, 3,510, and 3,733 for 1989 through 1998, respectively. Big 6 Auditor Portfolio Shares Auditor industry expertise is unobservable, so researchers must rely on proxies to estimate it. Yardley et al. (1992) develop a measure of auditor industry expertise that estimates industry specialization by the proportion of an auditor’s audit fees earned from one industry of all those served. As audit fee information has been unavailable until recently, researchers have used sales or assets or the square root of assets as the base to estimate the proportion of audit fees received from a particular industry. Similar to Kwon (1996), I estimate auditor portfolio shares as follows (hereafter, Big 6 auditor portfolio shares, or Big 6 PS): J ik Big 6 PSik = ∑ SALES ijk j =1 K J ik ∑∑ SALES ( (1) ijk k =1 j =1 where SALES is sales revenue, and the numerator is the sum of the sales of all Jik clients of audit firm i in industry k. The value of i ranges from 1 to 6, representing the Big 6 auditors. Two-digit SIC Accounting Horizons, Supplement 2003 4 Krishnan codes identify industry categories. The denominator in Equation (1) is the sales of all clients of audit firm i summed over all K industries. An example will demonstrate the computation of Big 6 PS for Coopers & Lybrand (CL) for the transportation equipment industry (two-digit SIC code 37). In 1989, CL had seven clients in the transportation equipment industry. For 1989, the total sales of these seven clients were $97,094.54 million (a large portion generated by a single client, Ford). During 1989, CL served 33 industries and audited 202 clients. The total sales of these clients amounted to $395,525.09 million. Big 6 PS for Coopers & Lybrand for the transportation equipment industry for 1989 is thus: Big 6 PSCL,Transportation equipment,1989 = $97,094.54/$395,525.09 = 0.2455. This suggests that the transportation equipment industry alone accounted for about a quarter of CL’s audit fees in 1989. As an auditor’s industry expertise may change over time, I repeat this step for each year and then aggregate CL’s portfolio shares over the years 1989 through 1998 for each industry. During 1989 through 1998, the total sales of all clients of CL in the transportation equipment industry amounted to $1,094,132.01 million. During the period, CL served 49 industries and audited 2,647 client-years. The combined sales of clients representing those 49 industries amounted to $6,350,583.13 million. Big 6 PS for CL using the aggregate data is computed as follows: Big 6 PSCL,Transportation equipment,1989–1998 = $1,094,132.01/$6,350,583.13 = 0.1723. The final step involves identifying industries in which CL is considered a specialist auditor. I code a firm’s top-three portfolio shares as the auditor’s specialty and the remaining industries as nonspecialty. For CL, industries that represent the top three portfolio shares are communications, transportation equipment, and food stores. To put it differently, these three industries are the top three moneymakers for CL during the period 1989 through 1998. Thus, CL is defined as a specialist auditor only for these three industries over the sample period. I repeat these steps for each Big 6 auditor to identify industry specializations. Table 1 reports industry specialization and portfolio shares for each Big 6 auditor for the pooled sample (year-by-year portfolio shares are not reported). With the exception of Arthur Andersen, the Big 6 firms appear to show an expertise in the transportation equipment industry, although the portfolio shares range from 29.6 percent for Deloitte & Touche to 12.4 percent for Ernst & Young. Big 6 Auditor Industry Market Shares I use an alternative measure of auditors’ industry expertise in order to minimize measurement error associated with estimation of auditors’ industry specialization and to enhance the reliability of the findings. Following Gramling and Stone (2001), I calculate an auditor’s industry market share to proxy for audit fees earned by an auditor in an industry as a proportion of the total audit fees earned by all auditors that serve that particular industry (hereafter, Big 6 auditor industry market share, or Big 6 IMS): J ik ∑ SALES ijk Big 6 IMSik = (2) j =1 IK J ik ∑∑ SALES ijk i =1 j =1 where SALES is sales revenue, and the numerator is the sum of sales of all J ik clients of audit firm i in industry k. The denominator is the sales of Jik clients in industry k summed over all I k audit firms in the sample with clients (Jik) in industry k. The denominator does not include the sales of clients of non-Big 6 auditors as the sample includes only clients of Big 6 auditors. To estimate industry market Accounting Horizons, Supplement 2003 Does Big 6 Auditor Industry Expertise Constrain Earnings Management? 5 TABLE 1 Big 6 Auditor Portfolio Shares for 1989–1998 Auditor Portfolio Shares (in %) Industry (SIC code) Arthur Andersen Coopers & Lybrand Ernst & Young Deloitte & Touche KPMG Peat Marwick Price Waterhouse Petroleum refining (29) Chemicals and pharmaceuticals (28) Air transportation (45) Communications (48) Transportation equipment (37) Food stores (54) Petroleum refining (29) General merchandise stores (53) Transportation equipment (37) Transportation equipment (37) Durable goods—wholesale (50) Chemicals and pharmaceuticals (28) Electrical and electronic equipment (36) Machinery and computer equipment (35) Transportation equipment (37) Petroleum refining (29) Machinery and computer equipment (35) Transportation equipment (37) 12.85 8.05 6.88 17.34 17.23 8.50 16.44 15.55 12.40 29.56 23.89 11.85 20.38 14.07 13.49 25.83 18.83 13.68 Sales is used as the base in calculating portfolio share. The following example illustrates the calculation of portfolio shares for Coopers & Lybrand (CL). For the period 1989 through 1998, the total sales of all clients of CL in the transportation equipment industry (two-digit SIC code 37) amounted to $1,094,132.01 million. During the same period, the combined sales of all clients across all industries served by CL amounted to $6,350,583.13 million. Thus, CL’s portfolio share for the transportation equipment industry = ($1,094,132.01/$6,350,583.13) × 100 = 17.23%. Portfolio shares for other Big 6 auditors are calculated in a similar manner. For each auditor, top-three portfolio shares are coded as industries where the auditor is considered a specialist. Total number of firm-year observations equals 24,114. The sample consists of 2,782 firm-year observations for specialist auditors and 21,332 observations for nonspecialist auditors. share for each auditor, I require a minimum of ten observations for each pair of two-digit SIC codes and calendar years. An example will demonstrate the computation of Big 6 IMS for CL for the transportation equipment industry. The numerator is the same for both Equations (1) and (2). In 1989, there were 47 firms (including firms audited by other Big 6 auditors) in the transportation equipment industry; their total sales amounted to $355,634.61 million. Big 6 IMS for CL for 1989 is calculated as follows: Big 6 IMSCL,Transportation equipment, 1989 = $97,094.54/$355,634.61 = 0.2730. This indicates that CL’s share of the transportation equipment industry is 27.3 percent. Repeating the steps for each of the other nine years, I aggregate CL’s industry market shares over the years 1989 through 1998. For the period 1989–1998, the total sales of all clients of CL in the transportation equipment industry amounted to $1,094,132.01 million. There were 629 firm-years for the transportation equipment industry, with combined sales amounting to $5,724,707.32 million. Big 6 IMS for CL for the period is: Big 6 IMSCL,Transportation equipment,1989–1998 = $1,094,132.01/$5,724,707.32 = 0.1911. Accounting Horizons, Supplement 2003 6 Krishnan Shares for other industries served and for each Big 6 auditors are computed the same way to identify industry specializations. Table 2 reports industry market shares of Big 6 auditors for the pooled sample for selected industries (year-by-year industry market shares are not reported). A specialty is defined as any industry by two-digit SIC code where the auditor’s market share exceeds 15 percent. For example, in the period 1989–1998, CL’s market share exceeded 15 percent in the following industries: metal mining, oil and gas, lumber and wood products, chemicals and pharmaceuticals, primary metal, fabricated metal, transportation equipment, communications, and food stores. According to this alternative measure, CL is defined as a specialist auditor for these nine industries for the period 1989–1998. TABLE 2 Big 6 Auditor Industry Market Shares for Selected Industries for 1989–1998 TwoDigit SIC Industry AA CL EY DT KPMG PW 10 13 20 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 45 48 50 53 54 Metal mining Oil and gas Food and kindred products Textile mill products Apparel and other finished products Lumber and wood products Furniture and fixtures Paper and allied products Printing and publishing Chemicals and pharmaceuticals Petroleum refining Rubber and plastics Stone, clay, glass, and concrete Primary metal Fabricated metal Machinery and computer equipment Electrical and electronic equipment Transportation equipment Scientific instruments Air transportation Communications Durable goods—wholesale General merchandise stores Food stores 41.35 50.84 14.26 7.11 19.82 61.67 25.93 44.72 16.78 15.05 18.63 9.25 43.95 9.57 8.38 8.43 6.83 4.20 13.96 44.59 7.47 3.48 10.02 2.23 30.38 18.96 14.46 4.37 6.05 17.99 0.46 6.64 6.67 15.28 2.66 4.11 0.52 20.42 23.72 6.26 4.12 19.11 6.59 0.00 50.26 2.37 1.24 45.26 10.24 3.29 18.62 54.83 43.64 1.74 3.77 9.97 22.20 5.55 23.85 21.74 31.05 14.81 19.74 10.92 16.66 13.75 11.56 35.22 14.29 10.02 44.03 2.53 2.39 3.49 12.13 19.06 13.95 5.49 3.79 18.28 21.27 22.16 0.28 1.33 11.43 14.13 5.78 6.27 8.12 32.79 4.57 2.18 10.67 71.73 23.35 37.57 3.98 5.38 19.34 13.14 2.41 0.86 13.31 10.08 10.78 16.88 17.13 7.71 8.28 5.72 20.99 29.14 43.28 14.97 24.66 16.75 4.37 4.62 10.86 5.32 11.66 18.04 21.18 1.49 14.13 12.25 52.74 10.31 22.29 25.08 37.46 55.86 4.77 35.35 21.38 38.98 20.99 15.17 38.66 1.26 12.94 7.77 10.50 7.09 Industry Market Shares (in %) AA: Arthur Andersen; CL: Coopers & Lybrand; EY: Ernst & Young; DL: Deloitte & Touche; KPMG: KPMG Peat Marwick; and PW: Price Waterhouse. Sales is used as the base in calculating industry market share. The following example illustrates the calculation of industry market shares for Coopers & Lybrand (CL). For the period 1989 through 1998, the total sales of all clients of CL in the transportation equipment industry (two-digit SIC code 37) amounted to $1,094,132.01 million. During the same period, the combined sales of all clients in the transportation equipment industry amounted to $5,724,707.32 million. Thus, CL’s market share in the transportation equipment industry = ($1,094,132.01/$5,724,707.32) × 100 = 19.11%. Industry market shares for other industries are calculated in a similar manner. An auditor is coded as a specialist in industries where the auditor’s market share exceeds 15 percent. Bold indicates that auditor is a specialist. Total number of firm-year observations equals 24,114. The sample consists of 12,221 firm-year observations for specialist auditors and 11,893 observations for nonspecialist auditors. Accounting Horizons, Supplement 2003 Does Big 6 Auditor Industry Expertise Constrain Earnings Management? 7 Portfolio Share versus Industry Market Share Both portfolio share and industry market share indicate that CL has a specialty in the following industries: communications, transportation equipment, and food stores. In the other six industries, CL has a specialty based on industry market share but not portfolio share. A comparison of Tables 1 and 2 shows that this result is even more marked for the other firms. The industry market share measure tends to classify more firms as clients of specialist auditors than the portfolio share measure. About 51 percent of sample firms are classified as clients of specialist auditors according to industry market share, compared to about 12 percent according to portfolio share. An examination of year-by-year values of the portfolio shares and the industry market shares indicates that the top-three portfolios are fairly stable over the ten-year period for each Big 6 auditor (results not reported). The industry market shares exhibit more variation, suggesting that this may be a noisier measure of auditors’ industry expertise. This is consistent with Krishnan’s (2001) argument that portfolio share captures the efforts of auditors to differentiate their products better than industry market share, and may be a better proxy for auditor industry expertise than industry market share. Finally, the Pearson correlation coefficient (not reported) between portfolio share and industry market share is 0.45, significant at the 0.01 level. Pearson correlation coefficients between the two measures for each Big 6 auditor are positive and also significant at the 0.01 level for each auditor (results not reported). RESEARCH METHOD I estimate discretionary accruals using a cross-sectional variation of the Jones (1991) accruals estimation model also used by DeFond and Jiambalvo (1994).2 I use the absolute value of discretionary accruals (ABDAC) as a proxy for accruals-based earnings management (Becker et al. 1998; Francis et al. 1999). In other words, all else equal, higher ABDAC is consistent with a conclusion that auditors allow their clients to exercise greater accounting flexibility. Several variables have been identified that are correlated with discretionary accruals (Becker et al. 1998; Bartov et al. 2000): size (SIZE) defined as log of total assets, and leverage (LEV) defined as long-term debt divided by total assets. Since firms with higher absolute values of total accruals are likely to have greater discretionary accruals, I include the absolute value of total accruals divided by total assets at the beginning of the year (ABACCR) as a control variable. DeFond and Subramanyam (1998) find that discretionary accruals are related to auditor changes. I include a dummy variable (NEWAUD) equal to 1 if the first sample year is the first year with a new auditor, and 0 otherwise. Similarly, another dummy variable (OLDAUD) is set equal to 1 if the last sample year is followed by an auditor change, and 0 otherwise. Further, following Bartov et al. (2000), to control for growth, I include market-to-book (MKBK) ratio as a control variable. 2 Estimation of discretionary accruals involves two steps. First, nondiscretionary accruals are estimated using the crosssectional version of the Jones (1991) model. This model estimates nondiscretionary accruals as a function of the level of property, plant, and equipment, and changes in revenue: ACCR j ,t TA j ,t −1 = α1 ∆REV j ,t PPE j ,t 1 + α2 + α3 + e j ,t TAj ,t −1 TA j, t− 1 TA j, t− 1 where ACCRj,t is total accruals for firm j in year t; TA is total assets; ∆REV is change in net revenue; and PPE is property, plant, and equipment. Total accruals are calculated as the difference between net income before extraordinary items and discontinued operations and cash flows from operations. Consistent with prior research, this model is estimated separately for each combination of two-digit SIC codes and calendar years. Fitted values are defined as nondiscretionary (expected) accruals. Second, the error term in the model (the difference between total accruals and nondiscretionary accruals) represents the unexplained or discretionary component of accruals. The median estimates of α 1, α2, and α3 are –0.100, 0.049, and –0.071, respectively. The percentages of regression coefficients that are in the predicted direction are 68 percent and 96 percent for α2 and α3, respectively. The median adjusted R2 is 0.24. Accounting Horizons, Supplement 2003 8 Krishnan Finally, I include two performance-related controls. First is earnings persistence (PERSIST). Following Ali (1994), observations in each year are partitioned into ten groups according to the absolute value of change in income before extraordinary items. Observations in the four extreme deciles (top-two deciles and bottom-two deciles) are classified as low-persistence firms, and observations in the middle six deciles are classified as high-persistence firms. Second, observations with negative earnings (LOSS) are coded as 1; observations of profitable firms are coded as 0. In all, eight control variables are included: ABDACt = β0 + β1SIZEt + β 2 LEVt + β3 MKBKt + β4 ABACCRt + β 5NEWAUDt (3) + β 6OLDAUDt + β 7PERSISTt + β 8LOSSt + β9 SPECLST + µ t . The variable of interest, SPECLST, is defined in four ways. As a continuous measure it equals the auditor’s portfolio share or its industry market share. As a dichotomous measure, SPECLST equals 1 for specialist auditors and 0 for nonspecialist auditors, depending on the auditor’s portfolio share or industry market share. An observation of ß9 < 0 is consistent with the notion that specialist auditors are able to constrain accruals-based earnings management. RESULTS Pearson correlation coefficients for the variables in Equation (3) are reported in Table 3. Correlations for the portfolio share measure appear above the diagonal, and correlations for the market share measure below the diagonal. The correlation between SPECLST and ABDAC is negative as predicted and statistically significant at the 0.01 level for both measures of auditors’ industry expertise. This suggests that, other things equal, auditor industry expertise is associated with less accruals-based earnings management. Discretionary Accruals: Specialist versus Nonspecialist Auditors Panel A of Table 4 reports descriptive statistics separately for clients of specialist and nonspecialist auditors depending on the portfolio share measure, for income before extraordinary items over total assets at the beginning of the year, log of total assets, long-term debt over total assets, total accruals, absolute value of total accruals, absolute value of discretionary accruals, income-increasing discretionary accruals, and income-decreasing discretionary accruals.3 The results indicate that clients of specialist auditors are slightly more profitable, are larger, and carry less debt than clients of nonspecialist auditors. These differences are significant at the 0.01 level. Differences in mean and median values of measures of accruals-based earnings management for clients of specialist and nonspecialist auditors are significant at the 0.01 level for all the five measures. More important, clients of nonspecialist auditors report higher discretionary accruals than clients of specialist auditors. Panel B of Table 4 presents statistics for clients of specialist and nonspecialist auditors depending on industry market share. The differences in mean and median values of earnings management measures for clients of specialist and nonspecialist auditors are significant at the 0.01 level for four of five measures. In summary, the level of the absolute value of discretionary accruals is lower for clients of specialist auditors under both measures of auditor industry expertise. I also calculate mean and median values of ABDAC by year, and compare the ten annual means and medians of the clients of specialist auditors to the ten annual means and medians of the clients of nonspecialist auditors. The differences in mean and median are significant at the 0.01 level (results not reported). Table 5 highlights the differences in mean value of ABDAC between clients of specialist and nonspecialist auditors for each Big 6 auditor. The histogram in Panel A is based on portfolio shares. Clients of specialist auditors have lower discretionary accruals than clients of nonspecialist auditors 3 Mean, median, upper quartile, and lower quartile of discretionary accruals for the pooled sample are –0.006, –0.001, 0.044, and –0.051, respectively. Accounting Horizons, Supplement 2003 ABDAC SIZE LEV MKBK ABACCR NEWAUD OLDAUD PERSIST LOSS SPECLST ABDAC SIZE LEV 1.000 –0.293* –0.048* 0.005* 0.661* 0.035* 0.050* –0.038* 0.238* –0.088* –0.293* –0.048* 1.000 0.247* 0.010* –0.236* –0.075* –0.085* 0.332* –0.342* 0.193* 0.247* 1.000 0.004 0.007 0.006 –0.001 0.071* 0.050* 0.023* MKBK ABACCR 0.005 0.100 0.004 1.000 0.008* 0.002 0.001 0.003 –0.010 –0.005 0.661* –0.236* 0.007 0.008 1.000 0.035* 0.066* –0.017* 0.285* –0.062* NEWAUD OLDAUD 0.034 –0.075* 0.006 0.002 0.035* 1.000 0.012*** 0.001 0.050* –0.027* 0.050 –0.085* –0.001 0.001 0.066* 0.012*** 1.000 –0.016** 0.086* 0.016** PERSIST LOSS –0.038* 0.238* 0.332* –0.342* 0.071* 0.003 –0.017* 0.001 –0.016** 1.000 –0.026* 0.081* 0.050* –0.010 0.285* 0.050* 0.086* –0.026* 1.000 –0.064* SPECLST –0.094* 0.125* –0.037* 0.001 –0.077* –0.020* 0.007 0.067* –0.026* 1.000 9 Accounting Horizons, Supplement 2003 *, **, *** Represent statistical significance at the 0.01, 0.05, and 0.10 levels, respectively, for a two-tailed test Correlation coefficients for the portfolio share measure appear above the diagonal; correlations for the market share measure appear below the diagonal. All firms were audited by Big 6 auditors. Total number of firm-year observations is 24,114. When auditors’ industry expertise is measured based on the portfolio share measure, the sample consists of 2,782 and 21,332 observations for specialist and nonspecialist auditors, respectively. For the market share measure, the sample consists of 12,221 and 11,893 observations for specialist and nonspecialist auditors, respectively. See Tables 1 and 2 for definitions of auditors’ portfolio shares and industry market shares, respectively. ABDAC is absolute value of discretionary accruals where discretionary accruals are determined using the cross-sectional version of the Jones (1991) model (see footnote 2). SIZE is the log of total assets. LEV is leverage calculated as long-term debt divided by total assets. MKBK is market-to-book ratio. ABACCR is absolute value of total accruals divided by total assets at the beginning of the year. NEWAUD equals 1 if first sample year is the first year with a new auditor, and 0 otherwise. OLDAUD equals 1 if the last sample year is followed by an auditor change, and 0 otherwise. PERSIST equals 1 for firms with low earnings persistence and 0 for firm with high earnings persistence. Persistence is measured as follows: observations in each year are partitioned into ten groups based on the absolute value of change in income before extraordinary items. Observations in the four extreme deciles (top two deciles and bottom two deciles) are classified as low-persistence firms and observations in the middle six deciles are classified as high-persistence firms. LOSS equals 1 if income before extraordinary items is negative, and 0 otherwise. SPECLST equals 1 for clients of specialist auditors and 0 for clients of nonspecialist auditors. Does Big 6 Auditor Industry Expertise Constrain Earnings Management? TABLE 3 Pearson Correlation Coefficients for 1989–1998 10 Accounting Horizons, Supplement 2003 TABLE 4 Descriptive Statistics: Clients of Specialist versus Nonspecialist Auditors for 1989–1998 Panel A: Big 6 Auditor Portfolio Shares Mean Type of Accrual PROFITABILITY SIZE LEVERAGE ACCR ABACCR ABDAC Income-increasing DAC Income-decreasing DAC Median Specialist Nonspecialist t–statistic Specialist Nonspecialist z–statistic 0.008 5.908 0.163 –0.044 0.073 0.054 0.054 –0.054 –0.009 5.048 0.186 –0.055 0.099 0.080 0.074 –0.085 3.94 * 16.71* –6.56* 5.71 * –17.77 * –22.44 * –13.27 * 18.14* 0.048 5.538 0.128 –0.046 0.059 0.039 0.039 –0.038 0.040 4.915 0.136 –0.050 0.069 0.049 0.047 –0.052 4.09 * 14.61* –3.20* 4.27 * –9.74* –11.62 * –6.59* 9.70 * Nonspecialist t–statistic Specialist Nonspecialist z–statistic 0.045 5.412 0.151 –0.050 0.064 0.043 0.042 –0.044 0.037 4.611 0.114 –0.048 0.070 0.054 0.051 –0.056 7.23 * 28.00* 8.67 * –1.09 –7.32* –13.47 * –9.00* 9.97 * Panel B: Big 6 Auditor Industry Market Shares Mean Type of Accrual PROFITABILITY SIZE LEVERAGE ACCR ABACCR ABDAC Income-increasing DAC Income-decreasing DAC Specialist 0.003 5.565 0.188 –0.053 0.089 0.069 0.065 –0.073 Median –0.018 4.717 0.178 –0.054 0.103 0.085 0.079 –0.090 5.33 * 30.67* 3.53 * 0.36 –9.67* –13.73 * –9.00* 10.25* Krishnan * Represents statistical significance at the 0.01 level. Auditors are classified into specialists and nonspecialists based on their portfolio shares and industry market shares. See Tables 1 and 2 for definitions of portfolio shares and industry market shares, respectively. PROFITABILITY is income before extraordinary items over total assets at the beginning of the year; SIZE is log of total assets; LEVERAGE is long-term debt over total assets. ACCR is total accruals divided by total assets at the beginning of the year. ABACCR is absolute value of ACCR. ABDAC is absolute value of discretionary accruals. Discretionary accruals (DAC) are computed as the error term from the Jones (1991) model (see footnote 2). Income-increasing discretionary accruals are positive DAC. Income-decreasing discretionary accruals are negative DAC. Total number of firm-year observations equals 24,114 representing years 1989 through 1998. When auditors’ industry expertise is measured based on the portfolio share measure, the sample consists of 2,782 and 21,332 observations for specialist and nonspecialist auditors, respectively. For the industry market share measure, the sample consists of 12,221 and 11,893 observations for specialist and nonspecialist auditors, respectively. Tests are two-tailed. t-statistics are from t-tests of the differences in the means and z-statistics are from Wilcoxon two-sample tests. Does Big 6 Auditor Industry Expertise Constrain Earnings Management? 11 TABLE 5 Mean Values of Absolute Discretionary Accruals between Clients of Specialist and Nonspecialist Big 6 Auditors for 1989–1998 Panel A: Auditor Industry Expertise Based on Portfolio Shares 0 .0 9 0 .0 8 Mean Absolute Disc Accruals 0 .0 7 0 .0 6 0 .0 5 S p ecialist N o n -sp ecialist 0 .0 4 0 .0 3 0 .0 2 0 .0 1 0 AA CL EY DT KPMG PW B ig 6 A u d ito rs Panel B: Auditor Industry Expertise Based on Industry Market Shares 0 .1 0.09 0.08 e a n A b s Disc o l u t eAccruals D isc A MeanMAbsolute 0.07 0.06 S p e c i a l is t 0.05 N o n -s p e c i a l i s t 0.04 0.03 0.02 0.01 0 AA C L EY DT KPMG PW B ig 6 A u d ito r s Auditors are classified into specialists and nonspecialists based on portfolio share and industry market share. AA is Arthur Andersen; CL is Coopers & Lybrand; EY is Ernst & Young; DL is Deloitte & Touche; KPMG is KPMG Peat Marwick; and PW is Price Waterhouse. See Tables 1 and 2 for definitions of portfolio shares and industry market shares, respectively. Discretionary accruals are computed as the error term from the Jones (1991) model (see footnote 2). Total number of firmyear observations equals 24,114 representing years 1989 through 1998. When auditors’ industry expertise is measured based on the portfolio share measure, the sample consists of 2,782 and 21,332 observations for specialist and nonspecialist auditors, respectively. For the industry market share measure, the sample consists of 12,221 and 11,893 observations for specialist and nonspecialist auditors, respectively. Accounting Horizons, Supplement 2003 12 Krishnan in every case. The differences in mean value of discretionary accruals between clients of specialist and nonspecialist auditors are significant at the 0.01 level in a two-tailed test (results not reported). The histogram in Panel B is based on auditor industry market shares. Once again, clients of specialist auditors have lower discretionary accruals than clients of nonspecialist auditors, except in the case of Price Waterhouse. Overall, these findings are consistent with the notion that specialist auditors mitigate accruals-based earnings management more than nonspecialist auditors. Multivariate Analysis Results in Tables 4 and 5 do not control for research confounds that might be associated with discretionary accruals. Estimation of Equation (3) controls for variables correlated with discretionary accruals. I estimate Equation (3) year-by-year as well as for the pooled sample. Pooling data allows for more powerful tests because of the larger sample size. An upward bias in t-statistics due to cross-sectional correlation in regression residuals is, however, a concern with models using annual data (Bernard 1987). I address cross-sectional correlation in two ways. In the pooled model, I include nine yeardummy variables DY to indicate fiscal years 1989 through 1997 and 14 industry-dummy variables D I representing two-digit SIC code numbers 13, 20, 28, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 48, 49, 50, 58, and 73. Each two-digit SIC code represents at least 2 percent of the total sample. The objective is to capture time- and industry-specific commonalities in the dummy variable coefficients and thus reduce correlations among regression residuals. The second procedure involves estimating cross-sectional regressions for each year. Following Ali (1994), I test significance of parameter estimates using t-statistics for the cross-temporal distributions of the year-by-year estimates. I also examine intertemporal independence by analyzing correlations between residuals across years. Table 6 presents descriptive statistics for the pooled and year-by-year samples for variables in Equation (3) based on portfolio share. Results using both the dichotomous variable specification and the continuous variable specification are reported. SPECLST is negative and statistically significant at the 0.01 level for the pooled sample. Results for the year-by-year samples indicate that SPECLST is negative as expected in each of the ten years, and the mean coefficient is significant at the 0.01 level. The year-byyear results also indicate that the pooled results are not just due to use of a large sample. Table 7 reports the same descriptive statistics for the pooled and year-by-year samples for variables in Equation (3) based on industry market share. SPECLST is negative and significant in this case at the 0.05 level. Overall, the results indicate strongly that the level of absolute discretionary accruals is negatively associated with auditors’ industry expertise. In summary, the results hold under both measures of auditors’ industry expertise for both dichotomous and continuous variable specifications. Results are consistent with the notion that specialist auditors serve to mitigate accruals-based earnings management more than nonspecialist auditors. Additional Tests for Robustness of Findings I apply some additional tests to examine the sensitivity of my results to alternative variable definitions and model specifications. I use the cross-sectional variation of the modified Jones (1991) model to estimate discretionary accruals. The mean values of absolute discretionary accruals under the modified Jones model for clients of specialist and nonspecialist auditors are 0.053 and 0.076, respectively. The median values are 0.037 and 0.047, respectively. The differences in mean and median values are statistically significant at the 0.01 level. I re-estimate Equation (3) using discretionary accruals obtained from the modified Jones model, and the results are consistent with those already reported. For the market share measure, I increase the cutoff rate to 25 percent to identify specialist auditors and re-estimate Equation (3). The results are comparable to results reported in Table 7; SPECLST is negative and significant at the 0.01 level. Accounting Horizons, Supplement 2003 Does Big 6 Auditor Industry Expertise Constrain Earnings Management? 13 TABLE 6 Regression of Absolute Discretionary Accruals on Control Variables and Big 6 Auditor Portfolio Shares for 1989–1998 ABDAC t = β 0 + β1 SIZEt + β 2 LEV t + β3 MKBK t + β 4 ABACCR t + β5 NEWAUDt + β 6 OLDAUDt + β7 PERSISTt + β 8 LOSS t + β9 SPECLST + µ t Pooled Sample Dichotomous Variable Independent Variables Coefficients Intercept SIZE LEV MKBK ABACCR NEWAUD OLDAUD PERSIST LOSS SPECLST Adjusted R2 0.058 –0.005 –0.001 0.000 0.495 –0.001 –0.002 0.004 –0.000 –0.012 Year-by-Year Samples Continuous Variable t-statistic Coefficients t-statistic 30.97* –23.06 * –0.48 0.42 122.97 * –0.72 –1.28 3.77 * –0.38 –8.47* 0.479 0.058 –0.005 –0.003 0.000 0.537 0.002 0.000 0.004 –0.003 –0.042 31.49* –24.04 * –1.33 0.18 131.28 * 1.37 0.15 4.07 * –2.46** –5.01* 0.501 Mean Coefficients 0.058 –0.006 –0.012 0.000 0.497 0.000 –0.004 0.003 0.002 –0.007 t-statistic 13.57* –13.70 * –3.83* 1.00 17.89* 0.16 –2.59** 2.97 ** 0.97 –9.66* 0.467 Number Positive 10/10 0/10 2/10 6/10 10/10 4/10 2/10 9/10 7/10 0/10 *, ** Indicate two-tailed significance at the 0.01and 0.05 levels, respectively. Big 6 auditors are classified into specialists and nonspecialists based on their portfolio shares. Sales is used as the base in calculating the portfolio share (see Table 1 for more information on the calculation of portfolio share). ABDAC is absolute value of discretionary accruals where discretionary accruals are determined using the cross-sectional version of the Jones (1991) model (see footnote 2). SIZE is the log of total assets. LEV is long-term debt divided by total assets. MKBK is market-to-book ratio. ABACCR is absolute value of total accruals divided by total assets at the beginning of the year. NEWAUD equals 1 if first sample year is the first year with a new auditor, and 0 otherwise. OLDAUD equals 1 if the last sample year is followed by an auditor change, and 0 otherwise. PERSIST equals 1 for firms with low earnings persistence, and 0 for firm with high earnings persistence. Persistence is measured as follows: observations in each year are partitioned into ten groups based on the absolute value of change in income before extraordinary items. Observations in the four extreme deciles (top two deciles and bottom two deciles) are classified as low-persistence firms and observations in the middle six deciles are classified as high-persistence firms. LOSS equals 1 if income before extraordinary items is negative, and 0 otherwise. SPECLST equals portfolio shares for the continuous variable specification. For the dichotomous variable specification, SPECLST equals 1 for industries representing the top three portfolio shares and 0 for the remaining industries. Year-byyear results are based on the dichotomous specification. The specification for the pooled sample include nine year-dummy variables DY for 1989 through 1997, and 14 industrydummy variables DI representing two-digit SIC code numbers 13, 20, 28, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 48, 49, 50, 58, and 73. Total number of observations equals 24,114 consisting of 2,782 and 21,332 observations audited by specialist and nonspecialist auditors, respectively. Yearly firm-year observations are 1,481, 1,746, 1,806, 1,857, 2,046, 2,302, 2,624, 3,009, 3,510, and 3,733 for 1989 through 1998, respectively. The pooled sample aggregates the individual year samples. Means of individual-year parameter estimates are reported for the year-by-year models with t-values (with 9 degrees of freedom) estimated from the cross-temporal distribution of these estimates. Reported adjusted R2s for the year-by-year samples are cross-temporal means. I re-estimate Equation (3) using an alternate measure of auditors’ industry expertise—industry market share calculated using square root of total assets as the base instead of sales (Krishnan 2001). Once again, SPECLST is negative and significant at the 0.05 level. Next, I exclude two-digit SIC categories not represented by specialist auditors and estimate the equation using the remaining observations. The results indicate that absolute discretionary accruals are lower for clients of specialist auditors, and SPECLST is negative and significant at the 0.01 level. My results are not sensitive to the inclusion of utilities (SICs from 4000 and 4999). Accounting Horizons, Supplement 2003 14 Krishnan TABLE 7 Regression of Absolute Discretionary Accruals on Control Variables and Big 6 Auditor Industry Market Shares for 1989–1998 ABDAC t = β 0 + β1 SIZEt + β 2 LEV t + β3 MKBK t + β 4 ABACCR t + β5 NEWAUDt + β 6 OLDAUDt + β7 PERSISTt + β 8 LOSS t + β9 SPECLST + µ t Pooled Sample Dichotomous Variable Independent Variables Coefficients Intercept SIZE LEV MKBK ABACCR NEWAUD OLDAUD PERSIST LOSS SPECLST Adjusted R2 0.058 –0.005 –0.001 0.000 0.513 –0.001 –0.003 0.003 –0.001 –0.002 t-statistic 30.41* –23.08* –0.49 0.38 126.48* –0.69 –1.76*** 3.44* –1.05 –2.45** 0.488 Year-by-Year Samples Continuous Variable Coefficients t-statistic 0.058 –0.005 –0.001 0.000 0.513 –0.001 –0.003 0.003 –0.001 –0.005 30.08* –23.16* –0.45 0.38 126.49* –0.69 –1.76*** 3.45* –1.05 –2.08** 0.488 Mean Coefficients 0.057 –0.005 –0.012 0.000 0.517 0.001 –0.005 0.002 0.001 –0.005 t-statistic 11.81* –11.77* –3.84* 0.64 23.24* 0.27 –3.18** 2.50** 0.46 –2.34** 0.483 Number Positive 10/10 0/10 2/10 8/10 10/10 4/10 1/10 8/10 5/10 1/10 *, **, *** Indicate two-tailed significance at the 0.01, 0.05, and 0.10 levels, respectively. Big 6 auditors are classified into specialists and nonspecialists based on their industry market shares. Sales is used as the base in calculating the industry market share (see Table 2 for more information on the calculation of industry market share). ABDAC is absolute value of discretionary accruals where discretionary accruals are determined using the cross-sectional version of the Jones (1991) model (see footnote 2). SIZE is the log of total assets. LEV is long-term debt divided by total assets. MKBK is market-to-book ratio. ABACCR is absolute value of total accruals divided by total assets at the beginning of the year. NEWAUD equals 1 if first sample year is the first year with a new auditor, and 0 otherwise. OLDAUD equals 1 if the last sample year is followed by an auditor change, and 0 otherwise. PERSIST equals 1 for firms with low earnings persistence and 0 for firm with high earnings persistence. Persistence is measured as follows: observations in each year are partitioned into ten groups based on the absolute value of change in income before extraordinary items. Observations in the four extreme deciles (top two deciles and bottom two deciles) are classified as low-persistence firms and observations in the middle six deciles are classified as high-persistence firms. LOSS equals 1 if income before extraordinary items is negative, and 0 otherwise. SPECLST equals industry market shares for the continuous variable specification. For the dichotomous variable specification, SPECLST equals 1 for industries where the auditor’s market share exceeds 15 percent, and 0 for the remaining industries. Year-by-year results are based on the dichotomous specification. The specification for the pooled sample include nine year-dummy variables DY for 1989 through 1997, and 14 industrydummy variables DI representing two-digit SIC code numbers 13, 20, 28, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 48, 49, 50, 58, and 73. Total number of observations equals 24,114 consisting of 12,221 and 11,893 observations audited by specialist and nonspecialist auditors, respectively. Yearly firm-year observations are 1,481, 1,746, 1,806, 1,857, 2,046, 2,302, 2,624, 3,009, 3,510, and 3,733 for 1989 through 1998, respectively. The pooled sample aggregates the individual year samples. Means of individual-year parameter estimates are reported for the year-by-year models with t-values (with 9 degrees of freedom) estimated from the cross-temporal distribution of these estimates. Reported adjusted R2s for the year-by-year samples are cross-temporal means. As an additional diagnostic check, I compare the nondiscretionary accruals of clients of specialist auditors and nonspecialist auditors. The ability of the specialist auditors in constraining earnings management should be more evident in the level of discretionary rather than nondiscretionary accruals. Consistent with this expectation, I find that the differences in mean and median values of nondiscretionary accruals between the clients of specialist and nonspecialist auditors are not significant at the 0.10 level. Finally, I examine in a two-stage analysis whether self-selection of clients of specialist and nonspecialist auditors is driving the observed differences in discretionary accruals. In the first stage, Accounting Horizons, Supplement 2003 Does Big 6 Auditor Industry Expertise Constrain Earnings Management? 15 I run a logistic model of auditor choice similar to the one used by Francis et al. (1999) and compute the inverse Mills ratio (IMR) (see Berndt 1991, Chapter 11). In the second stage, I estimate Equation (3) after including the IMR as an additional independent variable. The results indicate that SPECLST is negative and significant at the 0.01 level. This finding mitigates concern that sample self-selection is driving the reported results. The results of all these additional tests confirm the basic finding that clients of nonspecialist auditors consistently exhibit higher levels of absolute discretionary accruals than clients of specialist auditors. CONCLUDING REMARKS The rise of accruals-based earnings management in recent years has prompted calls for reforms to restore confidence in reported accounting information. Specialist auditors have the expertise, the resources, and the incentive to constrain opportunistic reporting of accruals and thereby enhance the quality of earnings. This study examines whether auditors’ industry expertise mitigates the tendency of managers to engage in accruals-based earnings management. When Big 6 auditors are partitioned into specialists and nonspecialists, I find that clients of nonspecialist auditors exhibit higher levels of discretionary accruals than clients of specialist auditors. This finding persists after controlling for firm size, industry effects, and other factors that are known to affect discretionary accruals. In summary, the finding is consistent with the notion that auditors’ industry expertise moderates accruals-based earnings management. One implication is employment of a Big 6 auditor that is also an industry specialist can further enhance the credibility of accounting information. While audit firms have undertaken significant restructuring efforts along industry lines, empirical evidence on the payoff from these efforts is limited. The findings of this research support the notion that there are likely returns to investing in specialization in the form of increased audit effectiveness and associated credibility. I should note one caveat. One cannot rule out the possibility that audit clients with lower discretionary accruals tend to self-select specialist auditors, even though a sensitivity test suggests that the results are not driven by sample self-selection. REFERENCES Ali, A. 1994. The incremental information content of earnings, working capital from operations, and cash flows. Journal of Accounting Research (Spring): 61–74. Bartov, E., F. Gul, and J. Tsui. 2000. Discretionary-accruals models and audit qualifications. Journal of Accounting and Economics (December): 421–452. Becker, C., M. DeFond, J. Jiambalvo, and K. Subramanyam. 1998. The effect of audit quality on earnings management. Contemporary Accounting Research 15 (Spring): 1–24. Bedard, J., and S. Biggs. 1991. The effect of domain-specific experience on evaluation of management representation in analytical procedures. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory (Supplement): 77–95. Bernard, V. 1987. Cross-sectional dependence and problems in inference in market-based accounting research. Journal of Accounting Research 25 (Spring): 1–48. Berndt, E. 1991. The Practice of Econometrics: Classic and Contemporary. New York, NY: Addison-Wesley. Bonner, S., and B. Lewis. 1990. Determinants of auditor expertise. Journal of Accounting Research (28): 1–28. DeAngelo, L. 1981. Auditor size and auditor quality. Journal of Accounting and Economics 3 (December): 183–199. DeFond, M., and J. Jiambalvo. 1994. Debt covenant violations and manipulation of accruals. Journal of Accounting and Economics 17 (January): 145–176. ———, and K. Subramanyam. 1998. Auditor changes and discretionary accruals. Journal of Accounting and Economics 25 (February): 35–68. Accounting Horizons, Supplement 2003 16 Krishnan Dopuch, N., and D. Simunic. 1982. The competition in auditing: An assessment. In Fourth Symposium on Auditing Research. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign. Francis, J., E. Maydew, and H. Sparks. 1999. The role of Big 6 auditors in the credible reporting of accruals. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory 18 (Fall): 17–34. Gramling, A., and D. Stone. 2001. Audit firm industry expertise: A review and synthesis of the archival literature. Working paper, Georgia State University. Healy, P., and J. Wahlen. 1999. A review of the earnings management literature and its implications for standard setting. Accounting Horizons (December): 365–383. Johnson, P., K. Jamal, and R. Berryman. 1991. Effects of framing on auditor decisions. Organization Behavior and Human Decision Processes (50): 75–105. Jones, J. 1991. Earnings management during import relief investigations. Journal of Accounting Research 29 (Autumn): 193–228. Krishnan, J. 2001. A comparison of auditors’ self-reported industry expertise and alternative measures of industry specialization. Asia-Pacific Journal of Accounting & Economics (8): 127–142. Kwon, S. 1996. The impact of competition within the client’s industry specialization on the auditor selection decision. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory (Spring): 53–70. MacDonald, E. 1997. More accounting firms are dumping risky clients. Wall Street Journal (April 25). Maletta, M., and A. Wright. 1996. Audit evidence planning: An examination of industry error characteristics. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory (Spring): 71–86. O’Keefe, T., R. King, and K. Gaver. 1994. Audit fees, industry specialization, and compliance with GAAS reporting standards. Auditing: A Journal of Practice &Theory (Fall): 41–55. Solomon, I., M. Shields, and R. Whittington. 1999. What do industry-specialist auditors know? Journal of Accounting Research (Spring): 191–208. Wright, S., and A. Wright. 1997. The effect of industry specialization on hypothesis generation and audit planning decisions. Behavioral Research in Accounting (9): 273–294. Yardley, J., N. Kauffman, T. Cairney, and D. Albrecht. 1992. Supplier behavior in the U.S. audit market. Journal of Accounting Literature (11): 151–184. Accounting Horizons, Supplement 2003