BS 120 Field Natural History Spring 1 LAB 5 KINGDOM PROTISTA

advertisement

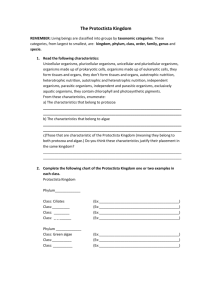

BS 120 Field Natural History Spring 1 LAB 5 KINGDOM PROTISTA Objectives: 1. To examine some typical examples of the diverse Kingdom Protista which includes all of the animal–like microorganisms of the Subkingdom Protozoa and of the plant–like microorganisms of the Subkingdom Algae, 2. To illustrate how complex cells of unicellular Protistans can be. 3. To have you, as a relatively gigantic organism, appreciate some of the special challenges faced by small unicellular organisms, and the adaptive solutions to these challenges that they have arrived at. 4. To learn the general differences between the various phyla. This lab presents a special challenge to you, one that takes practice and patience and a willingness to live with frustration. You may be ready to observe Euglena or Peridinium for example, but these highly motile organisms are living their own lives and will not readily stop and pose for you! Also, because you will be looking at very small organisms, the slides that you prepare from the stock cultures may not always contain what you are looking for. Sometimes the cultures we obtain are rich with organisms, other times there doesn’t seem to be as many. You won’t be able to see this until you put the slide under the microscope. When looking for organisms, be methodical and thorough, but don’t waste too much time. Go back and make another slide preparation. Methods: You are to obtain samples of protists from each of the phyla listed below. Use your survey handout to verify visible characteristics, and sketch each organism that you see. Some of the living organisms may require special techniques to prepare, and your instructor will review these in the pre-lab lecture. You will be responsible for knowing the differences between each of the phyla listed below by observing the representative species. In addition, you should know the general facts included in the description of each phyla. Please note that you should not use the oil immersion [100x] lens on your compound microscope but rather those capable of lower magnification, starting with the lowest magnification and working up to the 43x lens. Locomotory modes- An important criterion used in the classification of Protistans is their means of locomotion. Flagellates – Several major groups of Protistans move by means of one or two elongated, whip-like flagella. Among those that you should see today are Euglena, the dinoflagellate Peridinium and the Volvox culture. Some groups of flagellates are photosynthetic (autotrophic) , while others absorb organic nutrients and are non-photosynthetic (heterotrophs). Ciliates – This large group moves by means of cilia, locomotory structures that are much smaller than flagella. Each ciliate organism has many cilia, which are coordinated by a “pseudo-nervous” system that allows the organism to swim in a very controlled fashion. Ciliates are nonphotosynthetic heterotrophic protistans; many are highly predatory. Ciliates that you will see today include Stentor, Paramecium, and the predaceous Didinium. Rev. 2/06 BS 120 Field Natural History Spring 2 Cytoplasmic streamers (Sarcodina)– Examples you should see today are Chaos and Difflugia, Diatoms and Ameoba. Ameobas are nearly transparent and difficult to view. They will be available as pre-mounted slides. Ameobas move by using a flexible cell membrane, which can be extended into pseudopods (false feet), by smooth, flowing movements of internal cytoplasm. Diatoms have a rigid silica skeleton, but there is a longitudinal grove in the motile species, and within this groove the inner, deformable membrane is in direct contact with the aquatic medium in which the diatom lives. Cytoplasmic streaming deforms the cell membrane in a coordinated front-to-rear “wave” that pushes against the water (or fluid medium), moving the diatom forward. Nonmotile Protistans – Many protistans have no means of locomotion, but are permanently attached to objects in their environment (the stalked ciliates) or are free-living plankton that are moved around by water currents. Photosynthetic protistans living in the plankton are utterly dependent on eddies and vertical water movements to keep them near the surface. Because they are denser than water, they otherwise would sink out of the well-lit upper layers of lakes and oceans to depths where it is too dark for them to photosynthesize. Because small organisms of the same density sink more slower than larger ones, and because small organisms are also more easily carried upwards by vertical eddy currents, there has been strong selection for small planktonic protistans. Small size can be viewed as one of the most basic adaptations of planktonic organisms. The movement of microorganisms through waterThe rapid swimming of organisms like Euglena, Paramecium and Stentor is a remarkable feat that has captured the interest of not just of biologists, but of engineers specializing in fluid dynamics. In absolute terms, of course, these microorganisms swim much more slowly than do fish. But when compared to larger swimmers on a matching scale, Protistan flagellates and ciliates are far faster: a) Protists can travel at speeds up to 100 body lengths per second, b) speedy fishes like tuna can achieve only about 10 body lengths per second c) the fastest human swimmer can travel just over 1 body length per second. This may explain why you have difficulty in keeping them in the field of view when they are on the move! The swimming speeds of fast protistans are all the more remarkable when one realizes that organisms of such small mass have negligible momentum. Unlike fish or a human, whose inertial momentum makes them glide through the water between strokes, a protistan stops dead between strokes – or it would if it didn’t have some continuous mechanism of propulsion. Fortunately, both cilia and flagella provide continuous propulsion; the protistan needs this, because without inertial momentum to carry it forward the viscosity (resistance to movement) of the water would create an insurmountable obstacle to getting anywhere. “To appreciate the nature of the viscous forces experience by microorganisms, we would have to swim in a fluid one million times more viscous than water. Even a pool filled with honey, the relative strength of viscous to inertial forces would be two orders of magnitude smaller than it is for microorganisms swimming in water, and a more appropriate fluid would be molasses or even tar” ("How microorganisms move through water. ", 1986 American Scientist, by G.T.Yates –an engineer!). This means that if a protistan had a discontinuous means of propulsion (like the arm motions of a human swimmer), it would not move forward at all, but would simply thrash in place. Rev. 2/06 BS 120 Field Natural History Spring 3 THE SUBKINGDOMS AND PHYLA OF THE KINGDOM PROTISTA The Kingdom Protista includes a variety of organisms that are either unicellular, multicellular, or in some cases are grouped into colonies. Protistans are divided into the animal–like Protozoans, which are covered with a cell membrane or pellicle and have specialized organelles such as contractile vacuoles, cytostomes, mitochondria, ribosomes, and flagella or cilia. The Subkingdom Algae includes all of the photosynthetic eukaryotic organisms which were separated from Kingdom Plantae, where they used to be included, due to their lack of tissue differentiation. The protistan kingdom also includes the slime molds, organisms that are believed to be related to the fungi, which we may observe during the fungi lab. The algae may be unicellular, multicellular, or in colonies. They are found in a variety of habitats such as submerged in water, on soil, on the bark of trees or on the surface of rocks. Algae have visible nuclei and chloroplasts which contain chlorophyll and other pigments. Typically there are seven Phyla of algae, and we will examine each today in lab. The Euglenoids are considered by some to be a mobile form of algae, because they possess chloroplasts, and are therefore autotrophic. Subkingdom Algae Phylum Euglenophyta (Euglena): We have prepared slides of Euglena. This Phylum shows the difficulty in dividing up the protists into protozoa and algae. Why? Phylum Chlorophyta (green algae): The Chlorophyta are believed to be the ancestors to green plants. The Chlorophyta contain some examples that exemplify why the Protists are sometimes considered a “catch-all kingdom.” Although Protists are generally unicellular, many species of Chlorophyta are colonial or multicellular. In colonial organisms, the cells making up the colony may be interconnected, and they function as a unit. The Volvox that you will see in lab today is a hollow ball of colonial cells, and there is a division of labor. Some cells are involved with reproduction and others are not. The dark green spheres inside are daughter colonies that will be released when the mother colony breaks apart. There are prepared slides and living samples of Volvox. Proto-Slo will not be necessary. In multicellular algae, different cells are specialized for different functions, such as in the large seaweeds. Some parts of the algae are like large leaves, while the holdfasts that attach to rocks are like roots. Rev. 2/06 BS 120 Field Natural History Spring 4 Spirogrya (also Chlorophyta) is characterized by a spiral chloroplast in each of its cells. It forms long filaments. Spirogyra can be found locally in freshwater. Phylum Bacillariophyta (diatoms): Look at the mixed or marine diatom slide (prepared slide). Diatoms are enclosed in a “shell” made of silica. They are widely used as abrasives in scouring powder, and toothpaste, and also in roadsigns and license plates because of their reflective qualities. Diatoms move by cytoplasmic streaming. Phylum Dinoflagellophyta (dinoflagellates): Obtain a prepared slide of Peridinium. They have two flagella that beat within two grooves, one perpendicular to the other. The dinoflagellates are the primary photosynthesizers in the oceans. Phylum Phaeophyta (brown algae): look at the sample of kelp (in the jar) (Laminaria) on display. This species can grow to be 100 meters long.( If this is not available, there will be a jar of Fucus, as Porphyra and Chondrus crispus. Phylum Rhodophyta (red algae): examine a sample of Rhodymenia on display (in the test tube). Red algae is the source of carrageenin which is used to make gelatin harden and ice cream smooth. Rev. 2/06 BS 120 Field Natural History Spring 5 Subkingdom Protozoa All protozoa reproduce asexually by cell division (fission) but a few exhibit some degree of sexual reproduction. They possess dormant stages, called cysts, which are resistant to drought, heat and freezing. Locomotion plays an important role in the classification of the protozoans into the Rhizopoda which move by flowing protoplasmic projections called pseudopodia, the Zoomastigina that move by flagella and the Ciliates that move by cilia. Other protozoa lack any means of locomotion (Sporozoa) and are all internal parasites of other organisms. Phylum Ciliophora (ciliates): prepare a slide of Dindinium/Paramecium using Proto-slo. Dindinium is a predaceous ciliate that feeds on Paramecium. Also look at the prepared slide if desired. Look for large, slipper-shaped cells with a groove down the middle. This is the oral groove, used to direct food into the “mouth” of the protozoan. The ciliates are considered to be the most complex of the protozoa. Phylum Euglenophyta (Euglena) – represents the true difficulty in classifying Protists. Euglenoids are heterotrophic, which means they’re more like animals (Protozoa). But they also have chloroplasts and are capable of photosynthesis, making them autotrophic, and much more like the Algae. Phylum Rhizopoda (sarcodines or amoebae like): prepare a slide of Chaos using a slide with a well. The rhizopods are amoung the largest unicellular organisms. They move by extending pseudopodia (false feet), and flowing cytoplasm into them. The pseudopodia can also flow around a food particle and engulf it. Rev. 2/06 BS 120 Field Natural History Spring 6 Phylum Zoomastigina (flagellates): Termite parasites are flagellates in this phylum. The protozoa are in a mutualistic relationship with the termites. What does this mean? To view the termite symbionts (Trichonympha), gently squeeze the abdomen of a termite until brown goo is projected from the anus. Dab this goo on a slide and add a drop of termite saline solution. Cover with a coverslip and scan for moving cells at 100X. Trypanosoma T. cruzi – Chagas disease –recall 1st lecture. Causes swelling of the eye, tiredness, fever, enlarged liver or spleen, swollen lymph glands, and sometimes a rash, loss of appetite, diarrhea, and vomiting. Transmitted by true bugs (Hemiptera) T. rhodesiense, T. gambiense – African sleeping sickness, transmitted by the Tsetse fly. Look for these serpentine shaped protests between the red blood cells. Rev. 2/06