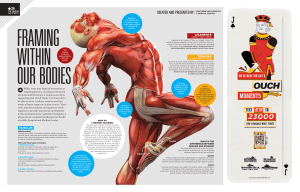

Skeletal Muscle Movement

advertisement

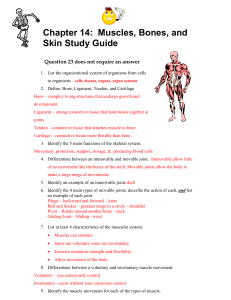

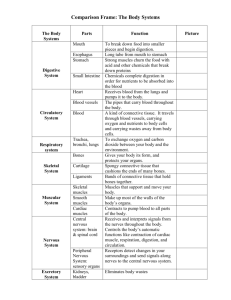

Skeletal Muscle Movement Skeletal muscles, which are the organs of the skeletal muscle system, generally act by pulling on bones to produce movement. To pull the bone, muscles need to attach to the bone, either directly or indirectly. The epimysium of a muscle can attach directly to bone or cartilage to form a direct attachment. An indirect attachment is formed when the connective tissue layers, the epimysium, perimysium, and endomysium form a complex at the end of the muscle. For connections, muscles require either a tendon or a broader sheet of connective tissue called an aponeurosis. Muscles connect to muscles via aponeuroses, and muscles attach to bones via tendons or aponeuroses. Thus, when a muscle contracts, the force of movement is transmitted through the attachment, which pulls on the bone to produce skeletal movement. Tendons also help to stabilize the joints. Tendons are a common form of attachment because the collagen fibers are more resistant to tearing than direct muscle tissue attachment to bone would be, and the compact form of the tendon requires a small amount of space. Tendons can be easily seen as the hand is flexed, causing the thick, cordlike tendons of the forearm to stand out prominently. The calcaneal (Achilles) tendon is visible from the heel to the calf. A connective tissue layer called a tendon sheath, which protects the tendon as it moves, also surrounds some tendons. Fluid-filled sacs called bursae also join to tendons to reduce friction as the tendon moves. Bursae are present in connective tissue near bone, where tendons experience friction, but they occasionally arise in other areas due to stress caused by movement. EXAMPLE Bursae can become inflamed, a condition known as bursitis. This is usually caused by overuse of a joint or by other mechanical stress, which can result in pain and swelling. Bursitis is common in knees, elbows, and shoulders. Keep in mind that the range of motion produced by muscles is restricted by the anatomy of the bones and other support structures involved in a particular joint. Consider the movements of the hip and shoulder joints, both of which are freely moveable. The hip is the attachment point for the thigh and leg. The shoulder is the attachment point for the arm and forearm. The shoulder can produce movements that the hip cannot because of the anatomy of the bones involved and the ligaments (connective tissue) associated with the joint. Hold your arm out to the side and move your thumb around the axis of the arm in a 360-degree circle. Can you do that with your hip and leg? No, you can’t. There are some people who appear to be “double-jointed"; they are able to push their joints past the normal limits of movement. The reason they can do this is because the ligaments of their joints are “loose” compared with someone who is not “double-jointed.” This ability appears to have a genetic basis. For muscles attached to the bones of the skeleton, the location of the connection determines the force, speed, and type of movement. These characteristics depend on each other and can explain the general organization of the muscular and skeletal systems.