Political economy and marginalist economics

advertisement

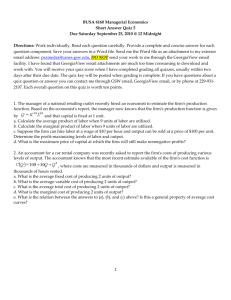

Political economy, marginalist economics and commissioning world view and practice The shift from political economy, swimming with anthropology, sociology, history and political science, to the discipline now with the title economics, with an altogether ‘dry’, smaller and better-defined territory, with a stricter methodological charter, is an important aspect of study not to be omitted when considering the view of markets used by what we have come to term ‘commissioning’. What we now call economics is more accurately a tendency, a school, stemming from Jevons’ theory of ‘marginal utility’ 1. In general, economists today favour mathematical modelling of axiomatised exchange relations over economic and other kinds of history; concentrate on individuals rather than classes or groups as economic agents; emphasise the preferences freely expressed in transactions rather than restrictive social circumstances; and describe self-sustaining equilibria of supply and demand when capitalist economies are striking for their growth and instability. Such marginal economics is in vogue with economists and politicians and, as you will come to see, is influential in how they, and through them we, have to (or not) see the world. Mathematical alibis leave context and real behaviour studiously ignored, even seen as irrelevant. This leaves political economy today as chiefly a pursuit of social scientists, and I would argue this can be seen in the gulf between the language and the world view the words depict and motivate. It’s a choice between complexity and ‘an easy way of acquiring the appearance of scientificity without having to answer the far more complex questions posed by the world’, as Thomas Piketty observes 2. The marginalist economist picture is an important building block of what we define as commissioning; how it comes to define what is a ‘market’ and what is validated as able to be included and that which isn’t, which is excluded. I am not a marginal economist and so my remarks have often elicited from those who are the response, ‘We’re not here not discuss that, the wider picture, only this….’ The messiness and complexity spoil a simple explanation that wants to settle for simplification rather than engaging with sophistication. Whilst it might look like common sense, deeper down those of us who are not marginal economists are quietly thinking (or in my case not so quietly) that real life cannot be explained in economic terms alone. 1 2 Explained in The Theory of Political Economy, William Stanley Jevons, 1871. st Capital in the 21 Century, Thomas Piketty, translated by Arthur Goldhammer, Harvard Press March 2014 There are two aspects I want to look at; the understanding of the creation of value and the methods used to do so. The biggest difference between the marginalists and the political economists concerns the question of economic value, and that last word ‘value’ is why it is such an important aspect for study when considering commissioning. Political economy holds that labour constitutes ‘the real measure of the exchangeable value of all commodities’, that is, all the inputs and the context are relevant. Prices are not irrelevant; when they don’t coincide with values, they at least oscillate around them. For a political economist, there is more to price and value than the speedy construction created by marginalists. For the marginalists, value is a function of marginal utility. In the famous example, diamonds cost more than water neither because they take more labour to procure nor because they are more useful, but simply because where water abounds and diamonds are scarce, the representative person anticipates more satisfaction in an ounce of diamonds than in another ounce of water, and pays accordingly. The same goes for capital of whatever physical or financial kind, and for the hours of workers with or without specific skills: the value of an additional or ‘marginal’ unit in the eyes of the purchaser sets the going price. If marginalism is right and, so far as markets are free, owners of capital and sellers of labour are paid exactly in line with their (marginal) productivity, then the freest markets will yield the fairest distribution of incomes and the most productive combination of labour and capital. In his recent book, Piketty writes of ‘the illusion of marginal productivity’: ‘It becomes something close to a pure ideological construct on the basis of which a justification for higher status can be elaborated.’ 3 As we have already analysed, the Residential Care Commissioning ‘market’ is no such thing but an oligopsony. Marginalist theories of value better explain price formation in the short run; labour theories are more persuasive about the long-run. There are substantial differences of method. To argue that value derives from labour as political economists do is to have to consider the successive and accumulated labours that go to make the history of the transaction. 3 st Capital in the 21 Century, Thomas Piketty To focus instead on the instantaneous balance of one person’s wish to sell with another’s wish to buy is to abstract a moment of harmony from the ongoing clangour and flux. Any possibility of the restraint of a market is repellent. With a political economic mode of thought it might be that one arrives at a conclusion that this is exactly what’s needed. Or indeed a method that was neither market nor regulation – Common Pool Resourcing. Jonathan Stanley Principal Partner NCERCC