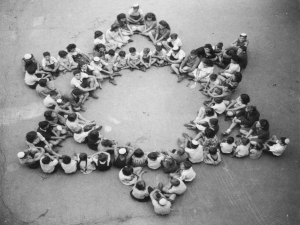

Forced Emigration of the Jews of Burgenland

advertisement