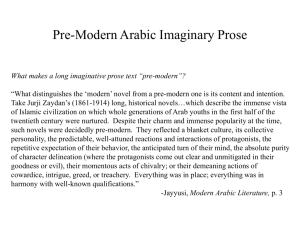

“ALL STRANGERS ARE TO ONE ANOTHER KIN,” Ibn

advertisement

“ALL STRANGERS ARE TO ONE ANOTHER KIN,” wrote the sixth-century poet Imru’ al-Qays in one of the oldest surviving pieces of literature written in Arabic. It predates by a century or so the revelations of the oldest Arabic book—the Qur’an— which also celebrates meetings beyond our own boundaries: God, it tells us, made mankind into nations and tribes “so that you may come to know one another.” From the Arabic shelves of my library, here are a few encounters beyond the borders of the familiar. The first comes from a description of Constantinople, quoted by the geographer Ibn Rustah. His informant, Harun ibn Yahya, had been captured by the Byzantines and taken to their capital. During his account of the imperial palace, Harun recalled a personal memory of Christmas dinner with the Christian emperor: T it y o f he emperor came to the hall and sat in the place of Th e r e lia b il h a s b e e n t n u o c c a s honor, at the table of gold, this being the feast-day of H a r u n’ cene, To m e th is s ow . d e n o the Messiah’s birth. He commanded that the Muslim ti s e u q il s th a t fo ll ta e d e th prisoners-of-war be brought in, and they were seated at the d n a ipti o n o f a n other tables ... on which was a huge variety of dishes both hot it – a de s c r m us ic , th e s and cold. Then the emperor’s herald proclaimed, “By the life o rg a n a n d ita ptive o f th e c of the head of the emperor, in these dishes there is not a trace g if t to e a c h o f tw o d ina r s p r e c is e s umh a m s – le n d it of the flesh of swine!” And the platters on which the prisonir p lus th r e e dg o f tr u th . ers’ food was served were of gold and silver. th e r in During the early Islamic centuries, the Arabs encountered furtherflung peoples through both conflict and commerce. Moving forward in time only a few years from Harun’s Constantinople but south some 6500 kilometers (4000 mi), the coast of what is today Mozambique is the setting for a tale recorded by the 10th-century sea captain Buzurg ibn Shahriyar. The story calls for a certain suspension of disbelief, but it bears witness to how mobile the Arab– Islamic world had become, and also to how the Arabs themselves could look into the mirror of other peoples, even if it reflected unflatteringly on themselves. Captain Buzurg heard the story from a fellow dhow-skipper, who in the year 923 had set sail on a trading voyage from Oman, in the southeast Arabian Peninsula, to Zanzibar, along the African coast. A storm, however, blew his ship far south of its destination. Eventually the skipper spied land: d With th eir ab lu tio ns an hen I made out the place, I realized we had arrived pr ay er s th e cr ew were ll at the land of the Zanj, who eat people, and that by perf or mi ng , wh ile sti of g making landfall here our doom was sealed. So we in sh wa e th al ive , ry ra ne fu d performed our ablutions, repented to Almighty God of our an se th e co rp an e ed ec pr at sins, and prayed the prayers for the dead over each other. th pr ay er s l. ria bu ic Isl am W Ib n Rus ta h a r o u n d 9 0c o m pil e d h is b o o k g e o g r a p h 0 c e . A s w e ll a s y (f r o m wh ic, th e s eve nth vo lum c o nta in s s h th e ex tr a c t c o m e e s) om a n d e n d s , e inter e s ti n g o d d s s “Th e Fir s t uc h a s a lis t o f Fo r in s ta n Per s o n To .. .“ ce, to m a ke s th e f ir s t p er s o n oa o th er th a n p wa s n o n e So lo m o n . “Za n j” wa s th e A r a b ic ter m c o ntem p o r a r y in h a b it a nts o fo r th e b la c k f c o a st , h er e inth e Ea st A fr ic a n Su fa la h (n ow th e r e g io n o f Th e a r e a wa in Moz a mb iq u e ). A r a b s, fo r it s li tt le k n own to th e la th a t c o u ld b e y b e y o n d th e r a n g e visi m o n so o n sa il te d in a si n g le in g se a so n .

![Procopios: on the Great Church, [Hagia Sophia]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/007652379_2-ff334a974e7276b16ede35ddfd8a680d-300x300.png)