Pre-Modern Arabic Prose

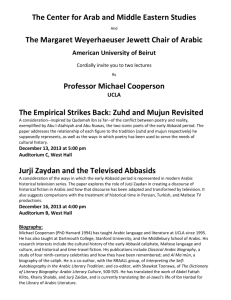

advertisement

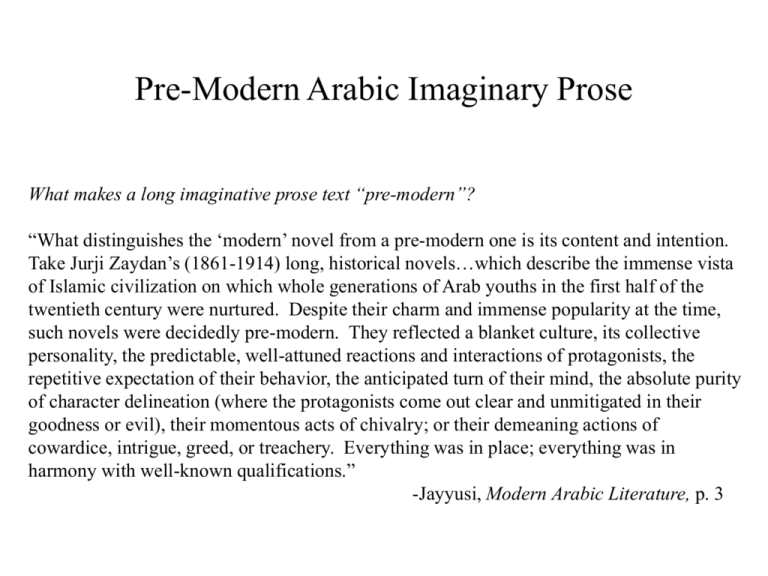

Pre-Modern Arabic Imaginary Prose What makes a long imaginative prose text “pre-modern”? “What distinguishes the ‘modern’ novel from a pre-modern one is its content and intention. Take Jurji Zaydan’s (1861-1914) long, historical novels…which describe the immense vista of Islamic civilization on which whole generations of Arab youths in the first half of the twentieth century were nurtured. Despite their charm and immense popularity at the time, such novels were decidedly pre-modern. They reflected a blanket culture, its collective personality, the predictable, well-attuned reactions and interactions of protagonists, the repetitive expectation of their behavior, the anticipated turn of their mind, the absolute purity of character delineation (where the protagonists come out clear and unmitigated in their goodness or evil), their momentous acts of chivalry; or their demeaning actions of cowardice, intrigue, greed, or treachery. Everything was in place; everything was in harmony with well-known qualifications.” -Jayyusi, Modern Arabic Literature, p. 3 You’ve already encountered a ”sbarA eht fo syaD ]elttaB[“account: ...al-Basus had a she-camel called Sarab. One day, Kulayb’s camel-herd passed by Sarab, who was tied in the backyard of Jassas b. Murrah. When Sarab saw the camels, she started to untie herself from the rope until it was cut off, and she followed the other camels and mingled with them. The herd reached Kulayb’s private precinct while he was at the watering place holding a bow and an arrow pouch. Kulayb saw Sarab but did not recognize her, so he grabbed an arrow and shot her and pierced her udder. The she-camel was startled and ran back slobbering, and when al-Basus saw her, she threw the veil off her head and cried: “wa dhullah, wa jarah” (O shame! O protector) and she went out. She incited Jassas, who rode his horse—and he was very proud of his horse—and took his weapon with him. ʿAmr b. al-Ḥarith b. Dhuhl b. Shayban followed him on his own horse carrying his spear, where they both entered Kulayb’s private precinct. Jassas said: “O Abu al-Majidah, you slaughtered the shecamel of my neighbor”. Kulayb responded “Why you! Do you intend to prevent me from protecting my private precinct?” And Jassas became so overwhelmed with anger that he stabbed Kulayb and broke his spinal chord, and ʿAmr b. al-Ḥarith stabbed him from behind and severed his lower back. Kulayb fell to the ground fidgeting and his two legs were twitching… How does this type of account differ from the other types of literature you read last night? The Qur’an Is the Qur’an literature? If so, what marks it as literary? In what ways is Surat Yusuf “novelistic”? Types of speech within the Qur’an: a) Brief (often enigmatic) prophetic utterances (sajʿ) b) Stories and narratives c) Rules and regulations Influence of the Qur’an on Arabic literature? Kalila and Dimna What marks this collection of stories as belonging to the realm of imaginary literature? What do these stories remind you of? What social and political service may these stories have played? Historical information: Translated from Middle Persian into Arabic by Ibn al-Muqaffa’ (d. 756 CE), a native Persian speaker. Stories originated in India from a collection of stories written in Sanskrit, known as the Pachitantra and attributed to the Hindu sage, Vishnu Sharma. The Epistle of Forgiveness, by al-Ma’arri (d. 1057 CE, and subsequently beheaded by Islamists militants in Aleppo [Syria] in 2013 CE) One of the earliest examples of extended imaginary prose; written, however, in conventional form as a letter (epistle) in which al-Ma’arri adopts the tone of Ibn Qarih – pedantic, pompous, preening, pious, and obsessed with obscure lexical knowledge - who had earlier written a critique of al-Ma’arri’s poetry. The Epistle is a sardonic take-down of the scholarly and religious orthodoxies of his era, as symbolized in his imagination by Ibn Qarih. Very sardonic; deeply critical of orthodox religious theologians and preening men-ofletters, such as Ibn al-Qarih, whose pretentions to great eloquence al-Ma’arri mocks throughout. Depicts visit of Ibn Qarih to heaven, where he meets and interrogates a number of literary, religious, and cultural figures (including a number of pre-Islamic poets, famous for drinking ample quantities of wine). In doing so, al-Ma’arri skewers the like of Ibn Qarih - who tries to bribe his way into heaven with some cliché poetry, amongst other things – and the self-righteous theologians of his age. Prefigures Dante’s Inferno? Hayy ibn Yaqzan - Written by Andalusi philsopher, Ibn Tufayl (d. 1185 CE) - A thought experiment: how awareness of God can be arrived at through the exercise of pure logic - The foundling, Hayy ibn Yaqzan (“Alive son of Awareness”), is raised by animals on an island. Through observation of the natural world and by interrogating his own facilities, emotions, and inclinations, Hayy bin Yaqzan arrives at a philosophical recognition of the Supreme Being - logic used in the service of faith - Mythopoetic echoes in the western religious and literary canon (Robinson Crusoe?) - The linear narrative is strictly in service to a didactic purpose (reason and philosophy conclude in spiritual awareness) The Maqama One of the first unique and truly indigenous Arabic literary prose genres, first composed by Ahmad “Badi’ al-Zaman” al-Hamadhani (d. 1008). Brief episodic or anecdotal texts set in the cities of the medieval Islamic world (Baghdad, Cairo, Basra, etc.) and typically featuring two stock characters: a gullible narrator/transmitter, Isa bin Hisham, and a wily swindler and hustler, Abu al-Fath alIskandrani. Very florid, exceedingly eloquent prose style (including long sections of rhymed prose or saj’) – “verbal pyrotechnics” - used in a humorous and parodic fashion, since the stories themselves describe the seedy underbelly of the medieval Islamic city, with its ethnic and linguistic hodge-podge of con artists, peasant rubes, hypocritical holy men, lazy students, and uncouth bedouin. Vignettes, no character or plot to speak of; comic, socially realistic (but not linguistically so); no psychological depth or development – instead, stock characters (grandiloquent dupe, trickster). The Arabian Nights No single text; a few manuscripts with different tales. There is no “original: version of The Arabian Nights. Indeed, the text of The Arabian Nights that we commonly encounter isthe product of Western scholarship and scholars who stitched together different Arabic manuscripts, collected stories from oral story tellers in the Arab world or from written fragments in libraries, and occasionally added their own stories (Ali Baba!). Did not influence the formation of the pre-modern Arabic literary canon; not considered “literature” by Arab literary critics and historians in the pre-modern era (this is not the case in the modern era though). Vernacular diction, depicts non-elites of medieval Cairo and Baghdad; socially realistic, yet with flights of fancy into the fabulous. Staggeringly intricate series of frame stories encompassing other frame stories; no over arching narratives. “In Nights, factuality, or what seems like factuality, is mixed with the wondrous and supernatural; mundanity is entwined with myth, human frailty with superhuman prowess. And above all, there is adventure, whether set within the possible or thrust into the domains of the humanly unattainable. There is no respite for the imagination; rather, a tireless soaring into spaces of an imagined and often unreachable world or into the realm of the senses with their incessant sensuality and passionate urges” (Jayyusi, Modern Arabic Fiction, p. 11).