The Acquisition of Similar and 'New' Chinese Syllable Initials by

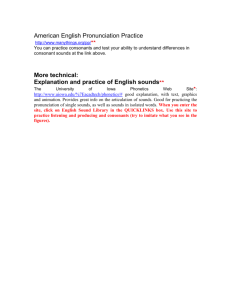

advertisement

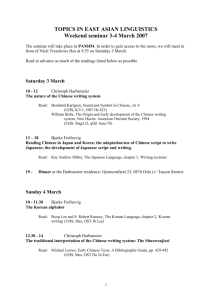

The Acquisition of Similar and ‘New’ Chinese Syllable Initials by Highly Proficient Korean Learners of Chinese Supervised by Professor Zhang Yanhui GUO Wei A Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Chinese Linguistics and Language Acquisition Department of Linguistics and Modern Languages, The Chinese University of Hong Kong June, 2013 Abstract of thesis entitled: The Acquisition of Similar and „New‟ Chinese Syllable Initials by Highly Proficient Korean Learners of Chinese Submitted by GUO Wei for the degree of Master of Arts in Chinese Linguistics and Language Acquisition at The Chinese University of Hong Kong in June 2013 It is commonly agreed that the onset age of second language (L2) acquisition has a crucial influence on the speakers‟ pronunciation. However, whether adult learners who begin L2 learning before or during puberty still show trace of accent remains to be a question. This study investigates the pronunciation of 10 Chinese syllable initials produced by early highly proficient Chinese learners of Korean and tries to prove that if learners start L2 acquisition between age 9 and 13, they can be detected with a foreign accent. By comparing the onset ages of the participants and their L2 proficiency, we could, to some extent, confirm the assumption that the later a learner starts his or her L2 acquisition, the more likely he or she is going to be detected with an accent. During our analysis in this study, we have also found that the previously or simultaneously acquired L2 English helps the acquisition of the L2 Chinese. Apart from that, the study does not find enough evidence to support the second language acquisition theory „Speech Learning Model‟ (SLM) that „new‟ sounds (referring to L2 sounds which have little similarity with L1 sounds) are acquired better than similar sounds since there is no significant difference between the acquisitions of these two kinds of sounds in our findings. Key words: Foreign accent; Age; New; similar; Transfer i 论文题目:对韩国早期高级汉语学习者汉语相似声母和“新”声母的习得研究 作者:郭炜 学校:香港中文大学 修读学位:汉语语言学及语言习得文学硕士 递交日期:二零一三年六月 提要: 众所周知,开始学习第二语言的年龄对学习者的语音有很大的影响,然而对在青春期 或之前就开始学习第二语言的学习者成年以后会不会留下口音的问题至今还没有定论。 本研究选取了五位韩国被试,他们很早就开始了汉语学习,是高水平的汉语学习者。 通过对五位韩国被试的 10 个汉语声母发音的研究和比较,我们试图证明,对 9 到 13 岁之间开始学习汉语的高水平汉语学习者,本族语者能够察觉出其口音,并且汉语学 习越晚的人比学习早的人越容易被察觉出口音。在分析的过程我们也发现,这些被试 之前或同时习得的另一门第二语言英语对于他们的汉语语音习得也产生了积极影响。 此外,由于本次实验结果显示汉韩之间“新”的音(即汉语和韩语之间相似度很小的音) 和相似的音的习得没有太大的差异,所以本次研究没有得出充足的证据来证明二语习 得理论“语音习得模型”,即“新”的音要比相似的音掌握得更好。 关键词:外国口音;年龄;新的音;相似的音;迁移 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisor Prof. Zhang Yanhui who has given me constant support and encouragement when I met all kinds of difficulties researching and writing this paper. Her warm smile, gentle words and positive attitude towards research and life inspires me in my future study and work. I am also grateful for the kindness of our executive officer Chris Cheung who always comforts me when I meet difficulties and helps me solve problems patiently. My special thanks go to Dr Fu Baoning who has taught me how to study during this challenging academic year and enlightened me when I was trapped in the difficulty of growing up and being independent. I would also like to express my sincere thanks to Prof. Ping Jiang-King who not only teaches us knowledge but also tells us the meaning of life. My sincere thanks also go to Prof. Thomas Lee, Prof. Gladys Tang, Prof. Gu Yang and Prof. Peng Gang who have opened the door for us to explore the profound and fantastic linguistic world. I also want to thank my dear friends Kim Bokyung, Cho Hyun Jae, Yuan Chenjing, Yang Zheng, Yang Wei, Hao Zhao, Li Bing, Cheng Dongliang, Yang Yike, Cheng Lanjun, Wang Yaxue and other friends who have helped me a lot in looking for the high-demanding participants and processing data, without whom I cannot complete my research paper successfully. Last but not least, I want to give my sincere thanks to my Bible teachers Richard and Jay who have enlightened my heart when I was troubled by anxiety and stress. Thank you all for your kind work! iii LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS L1 First Language L2 Second Language CAH Contrastive Analysis Hypothesis SLM Speech Learning Model CP Critical Perid FM Feature Model VOT Voice Onset Time iv LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES Table 1 Stimuli of the Similarity Perceptual Test for Distinguishing „New‟ and Similar Sounds 9 Table 2 „New‟ Korean and Chinese Consonants 10 Table 3 Similar Korean and Chinese Consonants 11 Table 4 Stimuli of the Similar and „New‟ Sounds Acquisition Test 15 Table 5 Score Frequency of the Chinese Group and Korean Group 18 Figure 1 Z Scores of Experimental and Comparison Group 18 Figure 2 Z Scores of Similar Sounds of Korean Speakers 20 Figure 3 Z Scores of „new‟ Sounds of Korean Speakers 20 v TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT..................................................................................................................................................... i ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ..............................................................................................................................iii LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS..........................................................................................................................iv LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES ................................................................................................................v TABLE OF CONTENTS ................................................................................................................................vi 1 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................... 1 2 LITERATURE REVIEW ............................................................................................................................. 2 2.1 Accent Detection Theory .................................................................................................................. 2 2.2 L2 Phonological Acquisition Theory ................................................................................................ 5 2.3 Multilingual Acquisition Theory ....................................................................................................... 8 2.4 Selection of „New‟ and Similar Sounds ............................................................................................ 8 2.4.1 Similarity Perceptual Test ...................................................................................................... 8 2.4.2 Introduction of the Corresponding Korean Consonants ....................................................... 11 3 RESEARCH QUESTIONS ....................................................................................................................... 13 4 METHODOLGY ....................................................................................................................................... 14 4.1 Participants...................................................................................................................................... 14 4.2 Stimuli ............................................................................................................................................. 14 4.3 Procedures ....................................................................................................................................... 15 5 FINDINGS ................................................................................................................................................. 17 6 DISCUSSION ............................................................................................................................................ 21 7 LIMITATION............................................................................................................................................. 24 8 CONCLUSION .......................................................................................................................................... 26 APPENDIX................................................................................................................................................... 28 REFERENCES ............................................................................................................................................. 29 vi 1 INTRODUCTION The phonological acquisition of a second language has always been a widely pursued issue. There are many theories and models discussing the issue of foreign accent in L2 acquisition. And the most influential one should be the Critical Period Hypothesis (Oyama, 1976; Tahta, & Loewenthal, 1981; Fledge and MacKay, 2003; Edwards, & Zampini, 2008). Lennerberg (1967) states that a speaker can achieve a native-like proficiency in pronunciation if he or she begins acquiring a language before or during puberty. Though it is highly controversial whether a critical period does exist and the beginning age and ending age of critical period for L2 acquisition, it is generally agreed that age has a close relationship with the nativeness of pronunciation (Bialystok, & Hakuta, 1994). Tahta, & Loewenthal (1981) suggest that age 6 and 12-13 are two kickpoints for L2 acquisition, because if L2 acquisition starts before age 6, a native-like proficiency could be reached; whereas if L2 acquisition begins after 13, an obvious accent could usually be detected. However, some linguists believe that native speakers are generally sensitive to foreign accent in the speech produced by non-native speakers. No matter when L2 acquisition begins, native speakers can always detect a clue to their non-nativeness (F1ege, 1984; Harada, 2006; Long, 1990; Ye, Cui, Zhu, &Lin, 1997: 1; Holm, 2008). Therefore, we wonder whether a foreign accent could be detected if L2 learners begin acquisition before or during puberty. Also, we would like to see if a later L2 learner has a more obvious accent than an earlier L2 learner. Apart from the foreign accent detection issue, the issue of what kind of sounds could be better acquired has been discussed for long. At first, Brown‟ Feature Model suggests that the successful acquisition of a sound depends on whether L1 has the same feature as the target L2 sound, indicating that L2 sounds which contain new features are hard to be acquired (Brown, 1997). The Contrastive Analysis Hypothesis (CAH) claimed similar sounds are better acquired because of 1 positive transfer (Chen, Wu, & Ma, 2005). However, this claim was not widely accepted because the similarity between sounds could cause learners‟ negligence of subtle difference between them, resulting in their inaccuracy in pronunciation. Later, the moderate version of CAH (Edwards, & Zampini, 2008) came up, which began to take into account the influence of slight discrepancy between two sounds. Then Best‟s Perception Assimilation Model (Best, 1991) and Fledge‟s Speech Learning Model (Fledge, 1987) all supported the claim that similar sounds are acquired worse than „new‟ sounds because of „phonological filtering‟ and „equivalence classification‟ (Fledge, 1987; Kent, 1992). Therefore, we would like to see whether this theory on sound similarity could be applied to early highly proficient L2 learners. We limit our range to early highly learners of Chinese who are native Korean speakers with both English and Chinese as their L2 while English is acquired earlier than or simultaneously with Chinese. So we are also wondering what influence the previously acquired L2 English might have on their later acquired L2 Chinese. 2 LITERATURE REVIEW 2.1 Accent Detection Theory It is generally accepted that age and input play important roles in language acquisition. Oyama (1976) believed that learners‟ nativeness is closely related to their onset ages of L2 acquisition. He proved this claim by studying American immigrants who began L2 English acquisition at different ages and concluded that the later a speaker started L2 acquisition, the more accent he or she is likely to be detected. Tahta, & Loewenthal (1981) agreed with Oyama‟s claim and further came up with the idea that L2 learners who began learning before age 6 could not be detected with a foreign accent (Oyama, 1976; Tahta, & Loewenthal, 1981). What is more, by investigating both early and late bilinguals who came to Canada 2 from Italy, Fledge and MacKay (2003) found that L2 learners who arrived in the L2 country before or during puberty period had better acquisition than those who arrived in late puberty or thereafter. Kuhl (1979) attributes this close relationship between age and accent to the fact that when people are young, they are sensitive to different sounds, however, as they become adults, this ability diminishes. Tahta, & Loewenthal (1981) further explained that with the increasing of age, people‟s neural plasticity which helps to establish a new articulatory pattern of L2 as well as to alter the existing acoustic system of L1 diminishes, so late L2 learners are more likely to ignore the difference between similar L1 and L2 sounds if not contrastive, and rely more on their pre-existing L1 acoustic experience without further modification. This is called „equivalence classification‟, which makes learners accustomed to different variations that belong to the same phoneme. It erodes human‟s ability to perceive contrast during L2 acquisition, thus resulting in their inaccuracy in L2 production(Rochet,1995). Moreover, though quite debatable, some linguists believe that there is a critical period (CP) for L2 phonological acquisition. If L2 acquisition commences after that period, nativeness is hard to be reached (Birdsong, 1999). Different people have different perspectives on when the critical period is, and up to now there has not been a fixed and clear answer to it. Tahta, & Loewenthal (1981) suggest that age 6 and 12-13 are two turning points of no foreign accent and obvious foreign accent for L2 acquisition respectively. In addition to the onset age of L2 acquisition, the length of using the target language is also closely related to the degree of foreign accent. The more a learner uses L2, the less likely there is an accent in their production (Edwards, & Zampini, 2008). Thus, the length of residence in L2 country should be taken into account when analyzing the foreign accent. What is more, it is believed that the detection of foreign accent is also closely related to the length of utterance. Holm (2008) claimed that compared to long 3 utterance, short utterance was hardly perceived to be non-native. However, there is a belief that non-native speakers could always be detected in their pronunciation. F1ege (1984) and Harada (2006) suggest that native speakers are sensitive to foreign accent even to very subtle acoustic difference. Further, Long (1990) claimed that non-nativeness could be detected even if L2 learners begin learning at a young age. And in our daily life, no matter how fluently an L2 learner could speak, native speakers can always detect a foreign accent in nonnative speakers‟ speech (Ye, Cui, Zhu, & Lin, 1997: 1; Holm, 2008). Fledge (1984) proved this claim by conducting a sophisticated experiment. The participants in his experiment were native American English speakers and native French speakers who took English as their L2. The stimuli are of different forms, varying from phrases to short phonemes even to the incomplete articulation of a segment such as the release part of a stop in English. The listeners range from people who are familiar with phonetics and have a good master of French language to those who have neither phonetic knowledge nor French learning experience. He made the listeners judge the sounds produced by these English and French speakers. Surprisingly, both groups of listeners could accurately distinguish between native English speakers and native French speakers. What is more, Harada (2006) did a further experiment to prove native speakers‟ sensitivity to foreign accent. He analyzed the acquisition of Japanese single and geminate stops produced by English speaking children. The result showed that even though English speakers were able to contrast the two kinds of Japanese stops, they still could be detected as non-native by native Japanese speakers. Park (2013) indicated that some research had studied the pronunciation in short stimuli by early bilinguals to show their difference from monolinguals, and some had tested the non-nativeness judgments by native speakers, however, few studies had directly combined them together---to directly test foreign accent in short materials produced by early highly proficient L2 learners. He made his study special by testing short stimuli produced by highly proficient learners who came 4 to L2 country around age 14 and have lived for at least 5 years there. The subjects in this study are different from previous studies including Park (2013)‟s study, because subjects are native Koreans who came to China before age 14 and have lived in China for at least 6 years. So the present study intends to investigate whether a foreign accent could be detected in short utterance like syllable initials produced by early highly proficient L2 learners who begin L2 learning before or during puberty and have a long residence in L2 country. We would also like to test whether the later a learner begins acquiring L2, the more foreign accent he or she is likely to be detected. 2.2 L2 Phonological Acquisition Theory The issue of acquiring similar and „new‟ sounds in L2 has been studied and discussed in many models either directly or indirectly. Among them, the most famous one might be the Speech Learning Model (Fledge, 1987), claiming that „new‟ sounds are more difficult to be acquired than similar ones. Apart from this, some classic theories have also implicitly discussed about the relationship between similarity and acquisition degree. Brown‟s Feature Model (FM) predicts that the properties of L1 influence the acquisition of L2. If the distinctive feature of an L2 sound also exists in L1, learners would perceive the sound accurately no matter whether they have heard of it before. However, if an L2 feature does not exist in L1, it is hard for L2 learners to perceive them (Brown, 1997, 1998). Accordingly, we might infer that „new‟ sounds which contain new features are hard to be acquired; and „similar‟ sounds which have the same features with L1 help L2 acquisition. Apart from FM, the Contrastive Analysis Hypothesis (Chen, Wu, & Ma, 2005) has also discussed the relationship between structure similarities and the acquisition of these structures. At first, it suggests that the resemblance between 5 sounds in two phonological systems causes positive transfer and the difference causes negative transfer. Therefore, it was assumed that the more differences between two sounds in L1 and L2, the more difficult it is for learners to acquire them (Wang, 2008). However, this claim does not seem to be convincing enough if studied further. Therefore, in Weinreich‟s study (as cited in Major, 2001), there was a detailed illustration on transfer which opposed the opinion that similarity only causes positive transfer. He believes that learners might neglect the difference between two L2 sounds if they are not contrastive in L1. Therefore, they usually substitute the most similar L1 sound for the corresponding L2 sound, resulting in the inaccuracy of pronunciation. Later in 1970, Oller and Ziahosseiny came up with a moderate version of Contrastive Analysis which was more widely accepted. It proposed that if two structures in L1 and L2 are similar but still has subtle difference, the one in L2 is difficult to be acquired. Though at first, this claim was only proved in spelling research by Oller and Ziahosseiny, it was soon generalized to phonetic studies and got explained in this way: in L1, people are used to the sounds which are contrastive and they tend to ignore the phonetic difference between sounds which do not distinguish meanings. Gradually people lose their sensitivity to phonetic distinction. Therefore, when they perceive L2 sounds, they might only perceive the ones which are different enough from L1 sound system, thus the phonetic differences of similar sounds between L1 and L2 are ignored. Larson (2004) indicates that due to this reason, learners tend to match L2 sounds mistakenly into L1 phonological space, thus making it hard for L2 learners to achieve native-like proficiency. Best‟s Perception Assimilation Model (Best, 1991) and Fledge‟s Speech Learning Model (Fledge, 1987) hold a similar assumption as Larson (2004), both claiming that the similarity between L1 and L2 is closely related to their perception and pronunciation (Best, 1991). Best‟s studies have proved that if two sounds in L2 are not contrastive in L1, it is hard for listeners to perceive and set new categories for them. Fledge claimed that if a L2 phoneme does not have a counterpart in L1 phonetic system, listeners could not find a category to classify them into, they 6 would establish a new cognitive category for that. If a phoneme in a second language has a similar one in the first language, the L2 learner would recognize it as belonging to a category in L1 rather than establishing a new one for it. As a result, the two sounds gradually merge together and the similar L2 sound would never be pronounced accurately. Therefore, it is stated that in L2 acquisition, similar sounds are never acquired completely, whereas new L2 sounds are acquired better because they are influenced much less by the existing L1 sound system. The phenomenon that similar L2 sounds are realized by using L1 phonetic pattern and are merged with corresponding L1 sounds regardless of the difference between them is called „phonological filtering‟ (Fledge, 1987). Also, Fledge points out that with the increase of age, similar sounds will become harder and harder to be recognized as a new category due to „equivalence classification‟ (Fledge, 1987). Also, by observing the acquisition of both English and Brazilian Portuguese as a second language from a longitudinal perspective, Major found that new sounds will be acquired increasingly successful whilst similar sounds are just the opposite as acquisition develops, thus he concluded that advanced L2 learners have a better master of dissimilar sounds than similar ones (Major, 2001). This is also supported by his theory „the Similarity Differential Rate Hypothesis‟, claiming that dissimilar sounds are acquired with a faster speed than similar sounds because transfer usually persists in similar sounds (Major, 2001). Therefore, it is indicated that new sounds are acquired better than similar sounds in the final stage of L2 acquisition. After reviewing these classic theories, we are wondering whether the theory that „new‟ sounds are acquired better than similar sounds could be applied to early highly proficient speakers of L2 who start acquiring L2 during puberty. 7 2.3 Multilingual Acquisition Theory Ringbom (1987) has indicated that the interaction between languages in a multilingual speakers‟ sound system could hardly be avoided. There are also many studies illustrating the influence of previously acquired L2 on the later acquired L2. Many research studies have supported the idea that a multilingual‟s sound system is different from that of a monolingual because the perception and production of a sound in a second language is influenced by the listeners‟ previously established sound system (Fledge, & MacKay, 2003; Best, McRoberts, & Goodell, 2001; Park, 2013; Ingram, & Park, 1997). Previously acquired L2 can help increase the learners‟ language awareness which assists to distinguish the similarities and differences between languages and thus influence the acquisition of later acquired L2. It is said that learners who have already acquired a second language have a better understanding of the relation between different languages, and this, to some extent, could help prevent the negative transfer from L1 when learning another L2 (Marx, & Horn, 2009; Gut, 2010). What is more, Wrembel (2010) suggested that compared to the influence of L1, previously acquired L2 has an even closer relationship with the later acquired L2. Therefore, for the Korean speakers we are going to test in this study, their previously acquired L2 -English must have an influence on their later acquired L2 – Chinese. 2.4 Selection of ‘New’ and Similar Sounds 2.4.1 Similarity Perceptual Test One of our purposes is to test whether „new‟ sounds are acquired better than similar sounds for advanced learners. Therefore, we need to first find out what „new‟ and similar sounds are between the Chinese and Korean sound systems. In this paper, we restrict our scope to syllable initials, i. e., Chinese consonants 8 (except ng/ŋ/). There are many studies holding different opinions about which consonants between Chinese and Korean are similar and which are different. It is said that there are various criteria to distinguish between similar and „new‟ sounds such as IPA symbols, acoustics, articulation, perception, native speakers‟ and nonnative speakers‟ intuitions (Fledge, 1990). Different studies use different criteria and there is no clear-cut and commonly agreed standard to judge similar sounds between two phonetic systems, which is a flaw of Fledge‟s theory (Wode, 1981). In this paper, we chose the non-native speakers‟ perception-based method to select similar and „new‟ sounds between Korean and Chinese sound system. Stimuli Twenty-one Chinese CV-structure syllables which contain all the consonants in Chinese Pinyin were listed. These syllables were exclusive of ng(/ŋ/) since ng(/ŋ/) does not appear initially in Chinese Pinyin. Vowels are limited to a(/a/) and i(/i/). Tones are all falling tones which are not totally new to Korean speakers because they have falling intonation in their language. The stimuli are listed below (as in Table 1). They are all pronounced by a 24-year old female speaker who is a native Mandarin speaker obtaining First Grade in Lower-Level of the Mandarin Proficiency Test. bà pà mà fà dà tà nà là gà kà zì cì sì jì qì xì rì zhì chì shì hà Table 1 Stimuli of the Similarity Perceptual Test for Distinguishing ‘New’ and Similar Sounds Scorers Scorers were 8 native Korean exchange students in The Chinese University of Hong Kong with different Chinese proficiencies ranging from beginning level to intermediate level. Their mean age is 22. Among them there are 7 female students and 1 male student. 9 Procedure Participants were tested individually in a quiet room to work on a forced choice and a rating test. A questionnaire was distributed to each of them with 18 Korean syllable initials listed on top of the paper for their reference. The participants were required to listen to the recordings of every Chinese syllable, and every syllable was played three times. During the playing of recordings, participants need to select the Korean consonant that is most similar to the Chinese syllable initial they had just heard. At the same time, they were asked to rate the degree of similarity between that Chinese sound and the Korean sound with a scale of marks ranging from 1-5 representing from the least similarity to the most similarity. They had unlimited time to judge and rate the sounds during the experiment, and the next syllable would not be read to them until they had finished their rating of each sound. Results By calculating mean values, we got the result that zh(/tʂ/), ch(/tʂ‟/), sh(/ʂ/), r(/ʐ/) and f(/f/) are the most different Chinese consonants with f(/f/) getting the lowest mean value. Below are the results of Korean sounds corresponding to those Chinese consonants: Chinese zh(/tʂ/) ch(/tʂ‟/) sh(/ʂ/) r(/ʐ /) f(/f/) Korean ㅉ (/t͈ ɕ/); ch(/tʂ‟/) ㅅ(/s/); ㄹ(/l /) ㅍ(/pʰ/); Consonants ㅈ (/t͈ ɕ /) Consonants ㅆ(/s͈ /) ㅃ(/p͈/) Table 2 ‘New’ Korean and Chinese Consonants Meanwhile, b(/p/), t(/t‟/), m(/m/), n(/n/) and h(/x/) were judged as the most similar consonants with m(/m/) and t(/t‟/) getting the same highest mean value. The Korean sounds corresponding to those high-rated similar Chinese sounds b(/p/), 10 t(/t‟/), m(/m/), n(/n/) and h(/x/) are listed below: Chinese b(/p/) t(/t‟/) m(/m/) n(/n/) h(/x/) ㅂ(/p/); ㅌ(/tʰ/) ㅁ(/m/) ㄴ(/n/) ㅎ(/h/) Consonants Korean Consonants ㅃ(/p/) ͈ Table 3 Similar Korean and Chinese Consonants 2.4.2 Introduction of the Corresponding Korean Consonants Unlike Chinese and English, Korean has a three-way phonation contrast for affricates and stops respectively, namely, plain/lax, tense/reinforced and aspirated consonants (Lee, 1998; Lee, & Ramsey, 2000). The differences between these three kinds of consonants are that aspirated consonants are produced with a strong burst of air, tense consonants are produced with a constriction in the vocal cords, while lax consonants are articulated with less tension. What is more, lax sounds are slightly aspirated in the word-initial position (Kim-Renaud, 2009). Therefore, as for the VOT, an aspirated sound has the longest one, a lax sound has a shorter one and a tense sound has the shortest one. Among the similar sounds, ㅉ(/t͈ ɕ/), ㅈ(/t͈ ɕ/) and ㅊ(/ʨʰ/) are affricates distinguished by tense and aspiration respectively. ㅅ(/s/) and ㅆ(/s͈ /) are fricatives differentiated by tense only. Likewise,ㅂ(/p/) and ㅃ(/p͈/) are mainly distinguished by tense. 2.4.2.1 Comparison of Similar Chinese and Korean Sounds 11 Chinese b(/p/), t(/t‟/) and n(/n/) have similar places of articulation with Korean corresponding sounds. Sun (2007) suggests that the pronunciation of Chinese b(/p/) is somewhere between Korean ㅂ(/p/) and ㅃ(/p͈/) , but it is more similar to Korean tense sound ㅃ(/p͈/) despite of the fact that b(/p/) is more lax than ㅃ(/p͈/). As for the Chinese consonant t(/t‟/), its degree of constriction in vocal cords is between Korean lax sound ㄷ(/t/) and aspirated sound ㅌ(/tʰ/) (Ren, 2003). So the pronunciation of b(/p/) and t(/t‟/) by native Koreans might differ from those produced by native Chinese due to different degrees of constriction in vocal cords. Chinese m(/m/) and Korean ㅁ(/m/) are all bilabial nasal sounds, and they are quite similar perceptually (Kong, 2007). Ren (2003) indicated that Chinese n(/n/) is similar to both Korean ㄴ(/n/) and ㅇ(/ŋ/) while the former is with more resemblance, and this claim has been attested by our similarity perceptual test. Chinese h(/x/) and Korean ㅎ(/h/) are all fricatives but Chinese h(/x/) is a velar consonant while Korean ㅎ(/h/) is a glottal sound (Sun, 2007). 2.4.2.2 Comparison of Chinese and Korean ‘new’ sounds Korean sound system does not have a category of cacuminal consonants, so recognizing Chinese zh(/tʂ/), ch(/tʂ‟/), sh(/ʂ/) r(/ʐ/) as relatively new sounds is reasonable. Also, Korean language has no category of labio-dental sounds, so regarding f(/f/) as a new sound is also understandable. Chinese zh(/tʂ/), ch(/tʂ‟/), sh(/ʂ/) and r(/ʐ/) are articulated with the tip of the tongue retroflexing or cacuminal against the front part of the palatal. Though Korean ㅉ(/t͈ ɕ/)/, ㅈ(/t͈ ɕ/) and ㅊ(/ʨʰ/) are affricates as Chinese zh(/tʂ/) and ch(/tʂ‟/), and Korean ㅅ(/s/) and ㅆ(/s͈ /) are quite like Chinese sh(/ʂ/), they have different places of articulation and different gestures of the tongue from Chinese corresponding sounds. Korean affricates and fricatives are produced with the tongue tip against the back of the teeth, as well as with the laminal of the tongue 12 against the palatal part instead of retroflexing the tongue tip, which are quite like Chinese lingual-palatal sounds j(/t ɕ/), q(/tɕ‟/) and x(/ɕ/). So Chinese and Korean affricates and fricatives are quite different in pronunciation. As for the Chinese r, there have always been some disputes about its pronunciation. Some Chinese books such as Xiandai Hanyu(2002)have transcribed the Chinese r as /ʐ/ which is a fricative articulated somewhere between alveolar and palatal. While according to Choo, & O'Grady (2003), when Korean ㄹ(/l /) is in syllable-initial position, its allophone is a flap, and it moves fast against the alveolar ridge. So the Chinese r/ʐ/ and Korean ㄹ(/l/) have little in common. However, Wang (1979) believes that the Chinese r should be transcribed as /ɽ/, which is a retroflex flap with the tongue tip against post-alveolar region. In this condition, the Chinese r/ɽ/ and Korean ㄹ(/l/) have similar manners of articulation because they are both flaps. Lastly, the Korean ㅍ(/pʰ/) and ㅃ(/p͈/) are different from the Chinese f(/f/) in that ㅍ(/pʰ /) and ㅃ(/p͈/) are bilabial stops while f(/f/) is a labio-dental fricative. 3 RESEARCH QUESTIONS This study focuses on the following research questions. (ⅰ) Whether L2 learners who start L2 acquisition before or during puberty and have a long residence in the L2 country can be detected with a foreign accent in short stimuli? (ⅱ) Which sounds do these speakers acquire better, similar sounds or „new‟ sounds? (ⅲ) What influence will their previously or simultaneously acquired L2 have on the phonological acquisition of their another L2? 13 (ⅳ) Whether earlier learners of L2 have a better pronunciation than later learners? 4 METHODOLGY 4.1 Participants There are two groups of participants. One is an experimental group which consists of 5 native Korean speakers with both English and Chinese as their second language while English is acquired earlier than or simultaneously with Chinese. They are all early highly proficient Chinese learners and have lived in the northern part of China for 6-11 years. Their ages range from 9 to 13 which are before the end of puberty. Among them, 4 participants began acquiring Chinese at the age between 9 and 11, and only one started learning Chinese later at age 13.The comparison group consists of 5 native Chinese speakers with good command of spoken Mandarin (getting at least Second Class Grade in Upper-Level of Mandarin Proficiency Test). 4.2 Stimuli The stimuli in this experiment are CV-structure syllables as listed in Table 4. The tones of the stimuli are high-level tones. The consonants are „new‟ and similar consonants respectively. The vowels are a, u and e respectively. They are regarded by Korean speakers as vowels similar to their Korean counterparts and they are not difficult to produce (supported by the native speakers‟ similarity perception test which includes the judgment of vowel similarity between Chinese and Korean sound system). 14 Similar bā tā mā nā hā bū tū mū nū hū bē tē mē nē hē zhā chā shā rā fā zhū chū shū rū fū zhē chē shē rē fē Sounds New Sounds Table4 Stimuli of the Similar and ‘New’ Sounds Acquisition Test 4.3 Procedures The experiment was conducted individually in a quiet room. Before the experiment, participants were told about the experiment procedures in advance and that their speech would be recorded. The procedures are as follows: PowerPoint slides were shown to the participant with only one syllable on each slide. The sequence of the syllables was randomized and the slides were divided into 30 groups, each group consisting of 3 slides with different colors in different syllables. The colors were respectively red, orange and green. Note that every 15 syllable was presented three times discontinuously in the entire experiment in case participants did not pronounce them completely. The slides were shown to participants one by one. When a syllable was presented, a participant need to read it out aloud and remember the color of the syllable at the same time. Every participant was told that the interval between every two slides was very short so that when a new slide was presented, they need to read it out aloud immediately. After three consecutive syllables were presented, there was a color-Pinyin match task. Participants were required to match the color with corresponding Pinyin. The whole experiment seemed as if it aimed at testing the fast memorizing ability of participants. However, this color memory part was designed only to distract the attention of participants so that they would not pay much attention to their pronunciations. Thus we could get their pronunciations in a natural situation. After the experiment, we selected to score only syllables containing the vowel „a‟ such as bā, tā, mā, nā, hā and zhā, chā, shā, rā, fā, because according to the similarity perceptual test, a/ɑ/ is rated as the easiest vowel for Korean speakers to produce. Because of this, speakers would not pay much attention to the articulation of a /ɑ/ and be focused on the pronunciation of syllable initials. Then, we mixed the recordings of these sounds produced by Chinese and Korean speakers and did a grading test. The grading test was conducted in a quiet group study room in The Chinese University of Hong Kong. Ten native Chinese graders (the graders did not include anyone who had participated in the experiment before) were required to listen to the randomized recordings and rate the degree of accuracy of the target consonants on a 10-point scale (1 indicating „very inaccurate‟ and 10 indicating „very accurate‟). After about two weeks after the experiment when the graders had almost forgotten about the sounds they had heard, a transcription test was conducted. This time they were required to listen to the same recordings again as they had heard before and were asked to transcribe the initial consonants. 16 5 FINDINGS In the statistical analysis, the mean value of scores comparison group and experimental group got were calculated (comparison group: M = 8.306; experimental group: M = 7.31). A Wilcoxon Two-Sample test was also performed for the two groups. Though the comparison group did not get a remarkably high mean value, the test result showed that there is a statistically significant difference between the two groups. Therefore, we could deduce that highly-proficient Korean speakers who begin Chinese learning between age 9 and 13 with a residence of at least 6 years in the L2 country can be detected with an obvious foreign accent in short stimuli. If we look at the line chart created from Z-Scores data in Figure 1, with the left side representing Korean speakers‟ deviation from the mean value, the right side representing Chinese speakers‟ deviation, we will see that the scores of Korean group vary in a greater range than Chinese group. It can be seen both groups reach 1 standard deviation above the mean value, which means Korean speakers can acquire some L2 Chinese sounds with a native-like proficiency. This can be proved in sound f(/f/) whose mean value is quite similar to the f(/f/) in Chinese group. However, there are many scores in the Korean group which reach 4 deviations below the mean value, indicating there are still some sounds they cannot acquire very well, such as r(/ʐ/). Also, we conducted a frequency test and found that the scores comparison group got are distributed mainly among 8, 9 and 10, whilst the distribution of experimental group is relatively distributed, ranging from 1 to 10 as shown in Table5. By observing the data, we found that the extremely low scores such as „1‟ and „2‟ are mostly distributed in the r(/ʐ/) sound produced by Korean speakers. The extremely high and low scores of the Korean group indicate the unevenness in their acquisition of Chinese sounds. 17 Z Scores of Experimental and Comparison Group 2 1 0 -1 -2 -3 -4 Figure 1 Z Scores of Experimental and Comparison Group group Chinese Korean N N 1 . 6 2 . 10 3 2 17 4 2 15 5 8 38 6 36 64 7 70 97 8 161 95 9 105 75 10 116 83 score Table 5 18 Score Frequency of the Chinese Group and Korean Group What is more, the mean score every Korean participant got was also calculated and the result showed that the participant who started Chinese learning later than others got the lowest mean value 5.62 whereas the mean value of all participants is 7.301, indicating her relatively inferior acquisition than others. This might indicate that onset age of L2 acquisition does have some connection with foreign accent. We calculated the mean values of similar and „new‟ sounds in Korean group and also conducted a Wilcoxon signed-rank test between them. The result of Wilcoxon signed-rank test is not significant (p=0.818), indicating the Korean speakers‟ acquisitions of similar and „new‟ sounds are not significantly different (similar sounds: M= 7.292; „new‟ sounds: M = 7.328). Therefore, we do not have enough evidence to attest to Fledge‟s Speech Learning Model that similar sounds are acquired better than „new‟ ones. What is more, we can see from the Z Scores line charts in Figure 2 and 3 that there are more „new‟ sounds which are far below the mean than similar sounds, indicating that some „new‟ sounds are not acquired as evenly as similar sounds. 19 Z Scores of Similar Sounds of Korean Speakers 1.5 1 0.5 0 -0.5 -1 -1.5 -2 -2.5 -3 -3.5 Figure 2 Z Scores of Similar Sounds of Korean Speakers Z Scores of 'New' Sounds of Korean Speakers 1.5 1 0.5 0 -0.5 -1 -1.5 -2 -2.5 -3 -3.5 Figure 3 Z Scores of ‘New’ Sounds of Korean Speakers A Z-Scores Test was also conducted on each target sound respectively. Among them, the highest mean value 8.24 occurs on the new sound f(/f/), and the lowest mean value 6.10 occurs on the new sound r(/ʐ/). The variation of rā ranges from 20 the minimum score „1‟ to the maximum score „10‟, which is obviously greater than that of fā. This, to some extent, indicates the acquisition of rā varies greatly according to individual level. 6 DISCUSSION The findings above show that L2 learners who begin learning between age 9 and 13 with a residence of at least 6 years in the target language country still can be detected non-native in short stimuli. We have to admit that their failure to have a native-like pronunciation is partly due to the reason that some of their productions are scored really low. Take rā for example, some Korean speakers pronounced it very well that they got 10 on this sound, while some did not perform well so that they got 1. This phenomenon could be attributed to speakers‟ different proficiencies. However, our research experiment method also exerted a great influence on that result. As the experiment was conducted with a fast speed attracting the participants‟ attention to remembering the color, listeners had no time to think how a sound should be produced. In this circumstance, they easily ignored the accurate pronunciation of each L2 sound and pronounced the sound unconsciously. Thus, their first language, another L2 or even inter-language combination might interfere with the process of sound production, resulting in their foreign accent. Also, the lowest score of the latest Chinese learner indicates that age might have the possibility to have an impact on a speaker‟s accent. This, to some extent, could partially support the claim that with the increase of age, the neural plasticity gradually erodes and equivalence classification becomes more and more powerful. This change results in the inaccuracy of perception, and further influences the nativeness of production. Therefore, we might confirm the claim that later L2 learners achieve less native-like proficiency than earlier learners in pronunciation. 21 According to the Wilcoxon signed-rank test result, the scores of „new‟ sounds are not significantly higher than those of similar sounds, thus Fledge‟s theory on similarity cannot be confirmed. There are a few extremely low scores occurring on the new sounds such as r(/ʐ/) as we have mentioned before, while in similar sounds, rare extremely low scores could be found except one in b(/p/). Therefore, in the next part, we focus on explaining these particular sounds--- b(/p/), the highest scored f(/f/) and the lowest scored r(/ʐ/). Referring to the transcriptions of b(/p/) in the graders‟ perception experiment, we have found that the low-scored b(/p/) was transcribed as p(/p‟/) by Chinese graders. It is understandable for Korean speakers to mix b(/p/) and p(/p‟/). In Korean, the syllable initial ㅂ(/p/) is like Chinese initial b(/p/), but Koreanㅂ(/p/) has more aspiration and the aspiration is not as strong as Chinese p(/p‟/). What is more, a slight aspiration in syllable-initial position does not incur different meanings in Korean. So when pronouncing Chinese b(/p/) in the experiment, as the subjects‟ attention was distracted from pronunciation, Korean speakers‟ L1 transfer might work, resulting in the production of slightly aspirated Koreanㅂ(/p/). However, as aspiration (it does not have to be very strong) in Mandarin can distinguish meanings, when an aspiration is found, Chinese graders might easily recognize it as another phoneme p(/p‟/). Among the 10 sounds, f(/f/) gets the highest mean value. On the one hand, it might be because its manner of pronunciation is not that difficult and it is inherently easy to learn; on the other hand, learners‟ experience of L2 English might also be of some help. Therefore, though there is no labio-dental consonant in Korean sound system, English does have an f(/f/) which can help Korean speakers acquire Chinese f(/f/) because English f(/f/) and Chinese f(/f/) are identical perceptually (Zhao, 1996). Thus, we might infer that „similar‟ sounds are acquired less accurately than „new‟ sounds does not apply to this situation, 22 because English f(/f/) is identical with Chinese f(/f/), and it has a positive transfer to help Chinese acquisition. The lowest-scored consonant is r(/ʐ/), and its standard deviation is much larger than that of f(/f/). There are some significant scores which have larger deviations below the mean value, indicating that some Korean speakers‟ acquisition of r(/ʐ/) are not desirable. According to the result of similarity perception test which aims to classify similar and new sounds between Chinese and Korean, Korean consonant ㄹ(/l /) corresponds to two Chinese consonants. One is r(/ʐ/), and the other is l(/l/). In that experiment, the mean value of similarity between l(/l/) andㄹ(/l/) is 4.375, which is much higher than that between r(/ʐ/) andㄹ(/l/), which is 2.000. What is more, based on the graders‟ transcription test result, low-scored r(/ʐ/) produced by Korean learners tends to be transcribed as Chinese consonant l(/l/). Thus, we might infer that, in this case, the influence of English r(/ɹ/) is not that significant, and there must be some other factor which resulted in their pronunciation like l(/l/). One factor we cannot exclude is that Chinese r is difficult inherently in its articulation. There are different perspectives on the pronunciation of Chinese r. Meng, & Zhao (1997) and Huang & Liao (2002) believe that Chinese r is a voiced retroflex fricative, which is transcribed as /ʐ/. According to Maddieson‟s claim in 1984, in American English, /ɹ/ is more marked than /l/ because the proportion of liquids /ɹ/ represents is much smaller than that /l/ represents in the world languages. Therefore, though not enough evidence has been found, we boldly assume that Chinese r(/ʐ/) is more marked than l(/l/). According to Jusczyk, Smolensky, & Allocco (2002), marked structures are hard to be acquired. What is more, Eckman‟s Markedness Differential Hypothesis (MDH) demonstrates that marked structures are acquired slower than unmarked structures (Major, 2001). While in this study, though Korean participants are highly proficient Chinese 23 learners, they are still generally young with the oldest one being only 21. So it is very likely they are still in acquisition process. Because the learners‟ acquisition still develops, their acquisition rate of the marked r(/ʐ/) is slower than unmarked l(/l/). Therefore, it is reasonable for Korean speakers to pronounce l(/l/) rather than r(/ʐ/). Also, according to Practor‟s Hierarchy of Difficulty (Chen, Wu, & Ma, 2005), if a phoneme in L1 splits into two phonemes in L2, it would be most difficult for learners to acquire. As Koreanㄹ(/l/) corresponds to two Chinese phonemes l(/l/) and r(/ʐ/), it is reasonable for Korean learners to confuse the two sounds. However, Wang (1979) has a different transcription about Chinese r. He believes that there is not much friction when pronouncing Chinese r, so the r in Chinese is not a fricative but a retroflex flap, transcribed as /ɽ/. If we chose Wang (1979)‟s version that Chinese r is a retroflex flap, the undesirable acquisition of Chinese r could be explained in the following way: According to Choo & O‟ Grady (2003), Korean ㄹ(/l /) has different variations in different positions. When it occurs at the syllable initial, it is a flap. In this circumstance, Chinese r(/ɽ/) and Koreanㄹ(/l /) are quite similar in the manner of articulation because they are both flaps. Hence, though Korean speakers perceive Chinese r(/ɽ/) as a new sound which is quite different from Korean ㄹ(/l /), they are indeed very similar in the manner of articulation. So it attests to Fledge‟s theory that similar sounds are acquired better than „new‟ ones. This explanation seems more convincing than the first one. 7 LIMITATION There are several limitations which might affect the result of the study. First, from the result of each Korean subject‟s score, we infer that age has an influence on L2 acquisition because the least scored subject started Chinese 24 learning at the latest age. Though that participant‟s length of residence in China is not the shortest, there are still many other factors we need to consider about when judging the relationship between age and acquisition, and we cannot exclude the possibility that the lowest score in the latest learner might just be a coincidence. Therefore, we could conclude that the degree of acquisition of L2 might have a negative correlation with the onset age of L2 acquisition, but it is not convictive enough in this study. Second, as the participants in this study are required to be native Korean speakers who start learning Chinese before or during puberty, and have lived in China for at least 6 years, it is relatively difficult to find qualified subjects. So the number of Korean participants in this study is small and different ages of the participants might affect the experiment result. Third, in the similarity perceptual test to classify the similar and „new‟ sounds between Chinese and Korean, we only chose one criterion based on the perception of Korean speakers. Different methods might cause different results, thus our experiment result might not be very comprehensive. Also, we only chose a(/a/) and i(/i/) as finals of the stimuli. Since different vowels might have different influence on the preceding consonants‟ pronunciations, the result might not be very accurate. Fourth, in the discussion part, we use markedness theory to explain the acquisition of r(/ʐ/), but not enough evidence has been found to prove that Chinese r(/ʐ/) is more marked than l(/l/), which makes our explanation lack empirical support. Therefore, we hope that a more sufficient explanation of the acquisition of Chinese r(/ʐ/) could be found if this issue can be discussed further by other researchers. 25 8 CONCLUSION This paper has investigated the early highly proficient Korean speakers‟ acquisition of Chinese as an L2 by grading, transcribing and analyzing their pronunciation of similar and „new‟ syllable initials. According to the result of experiment, under the condition that the participants‟ attention was diverted from their pronunciation, these highly proficient Korean learners who began L2 learning before or during puberty and have lived in China for at least 6 years can be detected with a foreign accent in short stimuli. However, not all of the pronunciations by Korean speakers are with obvious foreign accent. For some of the consonants, Korean speakers can acquire very well as native Chinese, which means different sounds have different levels of acquisition. Also, the latest Korean learner got the lowest score among all the Korean participants. This result to some extent supports the claim that age is closely related to the acquisition of an L2, which gives more evidence to support the Critical Period Hypothesis. What is more, their previously or simultaneously acquired English has a positive transfer on their Chinese phonological acquisition such as f(/f/). This proves that similarity might cause learning difficulty which impedes acquisition, but identicality can cause positive transfer which helps L2 acquisition. However, this study fails to attest to Fledge‟s theory that „new‟ sounds are acquired better than similar sounds due to the non-significant p value. Though the mean value of „new‟ consonants is relatively higher than that of similar consonants overall in Korean speakers, there are still some„new‟ sounds which have lower scores than similar sounds. Among them, r(/ʐ/), as a „new‟ sound, got the lowest mean value, which was sometimes pronounced as Chinese l(/l/) according to the result of graders‟ perception transcription test. Two explanations are provided for this, the first one adopts Eckman‟s Markedness Differential Hypothesis (MDH) that marked structures are acquired slower than unmarked structures. We presume that r(/ʐ/) is more marked than l(/l/), and the Korean speakers are still in their process of L2 acquisition, therefore they did not acquire r(/ʐ/) well. However, this explanation does not have 26 sufficient evidence because whether Chinese r(/ʐ/) is marked and whether the participants are still in their process of L2 acquisition still need to be tested. While the second explanation seems more reasonable. It is believed that Chinese r is indeed a similar sound to Korean ㄹ(/l /) in the manner of articulation. The learners‟ negligence of subtle difference between them resulted in their inaccurate pronunciation. But this contradicts to the similarity perception test result which showed that Chinese r(/ʐ/) is a new sound to Korean phonetic system. The contradiction has exposed the shortcoming of Fledge‟s theory because there is no fixed and unified standard to classify „new‟ and similar sounds. Experiments of different methods can have different results on the judgments of similarity. Overall, our study shows that the degree of acquisition of 10 Chinese consonants by these early highly proficient Korean speakers are not at even level and could be detected with a foreign accent. What is more, we have proved that previously acquired L2 could bring positive transfer to help their acquisition in another L2. Also, age does have a close relationship with the speakers‟ acquisition though this has not been studied further in this paper. What is more, this study fails to confirm Fledge‟s theory that similar sounds are better acquired than „new‟ sounds because they are not significantly different. Although there are some limitations in our study such as the control of the participants and our experiment method, we do hope and trust our findings from the above listed experimentation and the research could provide some deeper insights and explanations into the phonological acquisition of L2. 27 APPENDIX Background Information of Korean Participants No. Age Gender Place of Birth 1 21 F Korea 2 20 F Korea 3 21 F Korea 4 21 F Korea 5 20 F Korea Place of Residence in China Harbin, Heilongjiang Beijing Xi‟an, Shanxi Qingdao, Shandong Jiaozhou, Shandong 28 Starting Age of Years of Arrival Residence in China in China 10 10 11 11 15 6 10 10 11 13 13 8 9 9 11 Age of Chinese Acquisition REFERENCES Archibald, J.(2000). Second Language Acquistion and Linguistic Theory. Malden, Mass: Blackwell. Barnes, J. D., & Ebrary, I. (Eds.), (2006). Early trilingualism. Clevedon, England, Buffalo: Multilingual Matters. Best, C. T. (1991).The Emergence of Native-Language Phonological Influences in Infants: A Perceptual Assimilation Model. Haskins Laboratories Status Report on Speech Research, 107, 1-30. Best, C. T., McRoberts, G. W., & Goodell, E.(2001).Discrimination of non-native consonant contrasts varying in perceptual assimilation to the listener‟s native phonological system. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 109(2), 775-784. Bialystok, E., & Hakuta, K. (1994).In other words: the science and psychology of second-language acquisition. New York: Basic Books. Birdsong, David. (1999). Whys and Why Nots of the Critical Period Hypothesis for Second Language Acquisition.In D. Birdsong (Eds.). Second Language Acquisition and the Critical Period Hypothesis. Lawrence Erlbaum Publishers. Brown, C.A.(1997). Acquisition of segmental structure: consequences for speech perception and second language acquisition. (Unpublished Ph. D. dissertation).McGill University. Brown, C.A. (1998).The role of the L1 grammar in the L2 acquisition of segmental structure. Second Language Research, 14 (2), 136-193. Chen, C. L., Wu, Y. Y., & Ma, H. H. (Eds.). (2005). Introduction to teaching Chinese as a foreign language. Shanghai: Fudan University Press. Choo, M., & O'Grady, W. D. (eds.) (2003). The Sounds of Korean: A Pronunciation Guide. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press. Edwards, J. G. H., & Zampini, M. L. (2008).Phonology and second language acquisition. Amsterdam; Philadelphia: J. Benjamins Pub. Co. Flege, J. E., Schirru, C., & MacKay, I. R. A. (2003). Interaction between the native and second language phonetic subsystems. Speech Communication, 40(4), 467-491. 29 Flege, J. E. (1984). The detection of French accent by American listeners. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 76(3), 692-707. Flege, J. E. (1987). The production of "new" and "similar" phones in a foreign language: Evidence for the effect of equivalence classification. Journal of Phonetics, 15, 47-65. Fledge, J. E. (1990). English vowel production by Dutch talkers: more evidence for the „similar‟ vs. „new‟ distinction. In J. Leather and A. James. (Eds.). New sounds 90: Proceedings of the Amsterdam Symposium on the Acquisition of Second-Language Speech, Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam. Flege, J. E., & Hillenbrand, J.(1984).Limits on phonetic accuracy in foreign language speech production. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 76(3), 708-721. Flege, J. E., Munro, M. J.,& MacKay, I. R. A. (1995). Factors affecting strength of perceived foreign accent in a second language. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 97(5), 3125-3134. Gut, U.(2010) Cross-Linguistic Influence in L3 Phonological Acquisition. International Journal of Multilingualism, 7(1), 19-38 Harada, T. (2006). The acquisition of single and geminate stops by Englishspeaking children in a Japanese immersion program. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 28(4), 601–632. Holm, S. (2008). Intonational and durational contributions to the perception of foreign-accented. Ph.D. dissertation. Norwegian University of Science and Technology. Ingram, J. C., & Park, S. (1997). Cross-language vowel perception and production by Japanese and Korean learners of English. Journal of Phonetics, 25(3), 343-370. Larson, H. J.(2004).Predicting perceptual success with segments: a test of Japanese speakers of Russian. Second Language Research, 20(1), 33-76. Lee, D. (Eds.). (1998). Korean Phonology: A principle-based approach. München: LINCOM Europa. Lee, I., & Ramsey, S. R. (2000). The Korean language. Albany: State University of New York Press. Lenneberg, E. H. (1967). Biological Foundations of Language. Wiley 30 Liao, X. D., & Huang, B. R. (3rd revised eds.).(2002).Xiandai Hanyu. (pp.31). Beijing: Higher Education Press. Long, M. H. (1990). Maturational Constraints on Language Development. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 12(3), 251-285. Jusczyk, P. W., Smolensky, P. & Allocco, T. (2002).How English-Learning Infants Respond to Markedness and Faithfulness Constraints. LanguageAcaquisition, 10(1), 31-73. Kent, R. D. (1992). Intelligibility in speech disorders: Theory, measurement, and management. Amsterdam; Philadelphia: J. Benjamins Pub. Kim-Renaud, Y. (Eds.), (1975). Korean Consonantal Phonology. Seoul: S.n. Kim-Renaud, Y. (Eds.),(2009). Korean: An essential grammar. London; New York: Routledge. Kuhl, P. K. (1979). Speech perception in early infancy: Perceptual constancy for spectrally dissimilar vowel categories, The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 66(6), 1668-1679. Maddieson, I. (Eds.) (1984). Patterns of sounds. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press Major, R. C. (Eds.) (2001).Foreign accent: The ontogeny and phylogeny of second language phonology. Mahwah, N.J.: L. Erlbaum. Marx, N. & Horn, M. (2009) Pushing the positive: encouraging phonological transfer from L2 to L3. International Journal of Multilingualism, 7(1), 4-18. Meng Z. M., & Zhao, J. M. (Eds.).(1997). Yuyin Yanjiu Yu Duiwai Hanyu Jiaoxue. Beijing: Beijing Language and Culture University Press. Moscovsky, C. (2001).The Critical Period Hypothesis Revisited. Proceedings of the 2001 Conference of the Australian Linguistic Society. Canberra: Australian National University. OllerJr, J. W. & Ziahosseiny, S. M. (1970). The Contrastive Analysis Hypothesis and Spelling Errors. Language Learning, 20, 2, 183-189. Oyama, S. (1976). A sensitive period for the acquisition of a nonnative phonological system, Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 5(3), 261-283. 31 Park, H. (2013). Detecting foreign accent in monosyllables: The role of L1 phonotactics. Journal of Phonetics, 41(2), 78-87. Ren, S. Y. (2003). Han Han Shengyun Bijiao. Ph.D. dissertation. East China Normal University. Ringbom, H. (1987). The role of the first language in foreign language teaching. Clevedon, Multilingual Matters. Rochet,B. 1995. Perception and production of second-language speech sounds by adults. In W. Strange. (Eds.), Speech perception and language experience: Issues in cross-language speech research.(pp.379-410). Timonium, MD: York Press. Singleton, D. (1987). Mother and other tongue influence on learner French. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 9, 327-346. Sun, W. H..(2007). Dui Hanguo Zhongxuesheng Hanyu Fuyin Zhi Jiaoxue Fangfa. Ph.D. dissertation. Northeast Normal University. Tahta, S., Wood, M. & Loewenthal, K. (1981). Foreign accents: Factors relating to transfer of accent from the first language to a second language. Language and Speech, 24, p65-272. Wang, L.(1979). Xiandai Hanyu Yuyin Fenxi Zhong De Jige Wenti. Zhongguo Yuwen,4,281-286. Wang Yunjia(2008). Cross-language comparison and L2 speech acquisition: Theories and issues. Dibajie Zhongguo Yuyinxue Xueshu Huiyi Ji Qinghe Wu Zongji Xiansheng Baisui HuadanYuyin Kexue Qianyan Wenti Guoji Yantaohui. Ye, J., Cui, L., Zhu, C.,& Lin, X. Q. (Eds.). (1997). Waiguo Xuesheng Hanyu Yuyin Xuexi Duice. Beijing: Language & Culture Press. Wode, H. (1981). Phonology in L2 acquisition: Learning a second language. Tübingen, Germany: Narr. Wrembel, M. (2010).L2-accented speech in L3 production. International Journal of Multilingualism, 7(1), 75-90. Zhao, D. M. (1995). English Phonetics and Phonology ( As Compared With Chinese Features). Qingdao: Ocean University of China Press. 32