Syllabus - Joel Overall

advertisement

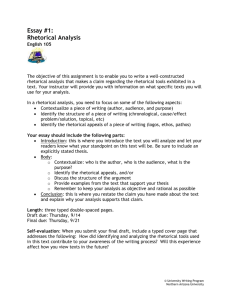

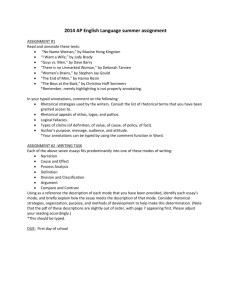

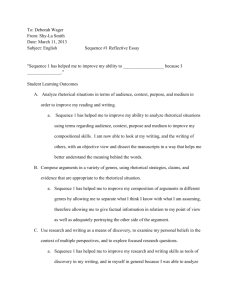

English 30243: Rhetorical Practices in Culture Course Objectives, Policies, and Syllabus Instructor: Email: Office: Office Hours: When: Where: Joel Overall joel.overall@tcu.edu Reed 402 MW 1-5 MWF 10-10:50 Bailey 106 Texts: Jack Conroy, The Disinherited (1933) Langston Hughes, The Ways of White Folks (1933) Clifford Odets, Waiting for Lefty (1935) John Steinbeck, Harvest Gypsies: On the Road toward the Grapes of Wrath (1936) John Steinbeck, In Dubious Battle (1936) Course Outcomes: • Demonstrate an ability to analyze diversity within/across culture. • Demonstrate the ability to use writing as a means of gaining and expressing an understanding of discipline-specific context. • Demonstrate an understanding of cultural conversations of 1930s America by discussing and writing about assigned texts. • Use the rhetorical theory of Kenneth Burke to explain the rhetorical nature of all texts and to analyze how 1930s texts shape and are shaped by their cultural scene. • Compose a multimodal presentation that provides historical/ cultural background about key events or institutions of Depression-era America. • Synthesize and integrate the ideas of others into a rhetorical history project, balancing their own voices with other sources and using standard MLA ciation style. The Culture Wars of 1930s America: Kenneth Burke wrote of the early 1930s that it was “a time when there was a general feeling that our traditional ways were headed for a tremendous change, maybe even a permanent collapse.” At stake, then, for Burke and artists and activists of the Depression era was nothing less than the fate of the country. This course examines the culture wars of the 1930s: the rich rhetorical and literary practices of Marxists, fellow travelers, liberals, and conservatives as they battled over questions not only of what direction the country should take politically and economically, but also of how “the good life” might be defined and, more importantly, what kind of texts--and by whom and in what forms (novels? plays? speeches? photographs? paintings? music?)--would help bring this good life into being. We’ll study some of these texts, and when we do so, we’ll be reading them rhetorically-that is, with an eye to analyzing how language (and symbols, more generally) create effects on audiences. English 30423: Rhetorical Practices in Culture Course Objectives, Policies, and Syllabus Course Requirements Travel Guides Travel guides are a very 1930s genre: the Federal Writers’ Project commissioned writers (Zora Neale Hurston was one) to write guidebooks for every state and to collect samples of folklore and folksongs. Travel guides are an appropriate genre for us because we have such little knowledge of the decade we’re “travelling” through this semester. Five times throughout the semester you will turn in 350500 words (1.5-2 double-spaced typed pages) of writing that includes your analysis to some readings. The final TG will be an in-class presentation of the 1930s figure you’ve studied. Travel guides are designed to enable you to explore aspects of the 1930s we can’t cover in class, broaden your understanding of 1930s people, events, and texts, and prepare you to compose rhetorical history projects by giving you practice analyzing a variety of texts. Rhetorical History Project For the rest of this semester, we will work together on a rhetorical history project: a collaboratively written “reader’s guide” to the culture wars of the 1930s. The culture wars were on-going conversations—struggles—to redefine America and to determine the best means of rebuilding a vigorous and wholesome society. That is, we will place important artists, critics, and politicians in a 1930s “rhetorical parlor,” a social space where they are engaged in all kinds of cultural “conversations” that help shape their texts and to which those texts respond. This project will consist of three main assignments: 1) an introductory essay; 2) a collaborative multimedia project; and 3) a rhetorical analysis. RH1: Introductory Essay Our first step is to find out as much as we can about the 1930s. We’ll build our rhetorical parlor by studying and sharing information about some significant figure from the 1930s. We’ll start with a class blog with individual wikipedia pages. Then, each person will write an overview of an important artist, critic, or politician, including a summary of 1-3 texts by this figure. You will write an essay (5-7 pages) that gives us an overview of a 1930s artist, critic, social movement leader, or political figure and a few of his/ English 30423: Rhetorical Practices in Culture Course Objectives, Policies, and Syllabus RH2: Collaborative Multimedia Project The second part of the rhetorical history assignment is a collaborative mini-documentary film focusing on one aspect of 1930s history. Your group will be responsible for collecting a substantial assortment of images, graphics, videos (if available), maps, and music along with textual research (spoken or written onscreen) and for arranging these elements in a documentary film to provide a comprehensive understanding of the subject. Your research for this documentary should go well beyond the Google image and/ or Wikipedia search, and we’ll have class time reserved to understand and practice the kind of research you’re expected to undertake. These documentaries will help develop our sense of the times, particularly some of the events our parlor figures witnessed or participated in or reacted to. RH3: Rhetorical Analysis Using the information we’ve gathered in Parts 1 & 2, you’ll write a rhetorical analysis, discussing how 1-3 texts by your parlor figure both respond to and are shaped by the on-going conversation in the “rhetorical parlor” of 1930s America. Your goal in the rhetorical history project is to help your classmates and me understand how your chosen text emerges from and responds to on-going cultural conversations of the 1930s. A rhetorical history is a rhetorical analysis (even if the text being analyzed is “literature”): the goal is not simply to help us better understand the text (though your analysis should do that); the goal is also to help us understand the text as a rhetorical act, an argument—as a product created by a particular writer in a particular culture for a particular audience and purpose. You’ll want to place your text in the rhetorical parlor: Who is the writer addressing? What’s s/he saying? Why—what has s/he read that provokes a response? What was going on that helped to shape your text? That is, show that we can explain/understand this text better if we know about “x” contextual information. In addition to the collaborative element of the assignment, you will write an informal 2-page paper describing the rhetorical choices made in the project and evaluating everyone in the group (including yourself) with a grade of excellent, satisfactory, and unsatisfactory. This individual essay will count 5% toward your final course grade. Grade Breakdown: • RH1: Introductory Essay • RH2: Collaborative Multimedia Project • RH3: Rhetorical Analysis • Travel Guides (5 @ 4% each) • Final Evaluative Experience her major texts “composed” between 1929 and December 1941. Your purpose is primarily informative, but you will need a thesis that makes a claim about your figure’s beliefs and/or importance. These essays will be posted on eCollege so that we all have access to each other’s research. 20% 25% 30% 20% 5% English 30423: Rhetorical Practices in Culture Course Objectives, Policies, and Syllabus Course Policies Attendance and Participation: Due to the collaborative nature of this course, it is important that you come to class every day and are involved in class discussions and activities. I will abide by the English department policy that states that 3 weeks worth of absences (9 absences) is grounds for failure of the course. Late Work: Major projects turned in late will be penalized 10% per day, including weekends. Homework will not be accepted late. Classroom Atmosphere: I envision our classroom as a place where all of us can share our ideas, thoughts, and questions without fear of being made fun of or embarrassed. Our classroom interaction will be based on respect for all of the writers and readers we encounter this semester. The Writing Center: The William L. Adams Writing Center is an academic support service available to all TCU students. Writing specialists and peer tutors are available for one-on-one tutorials from 8 to 5 p.m. Monday through Friday in the Rickel Building and from 6 to 9 p.m. in the library computer lab on Sunday through Thursday evenings. Drop-ins are welcome. The New Media Writing Studio: (NMWS) is available to assist students with audio, video, multimedia, and webdesign projects. Located in Rickel 38 (the basement of the Recreation Center’s academic wing), the Studio serves as an open lab for use by students during posted hours. The Studio has both pc and Mac computers outfitted with Adobe CS3, which includes Adobe Acrobat, Dreamweaver, Photoshop, Flash, and InDesign. A variety of equipment is available for checkout to students whose teachers have contacted the Studio in advance. For more information and a schedule of open hours, see www.newmedia.tcu.edu ADA: Texas Christian University complies with the Americans with Disabilities Act and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 regarding students with disabilities. Eligible students seeking accommodations should contact the Coordinator of Services for Students with Disabilities in the Center for Academic Services located in Sadler Hall, 11. Accommodations are not retroactive, therefore, students should contact the Coordinator as soon as possible in the term for which they are seeking accommodations. Further information can be obtained from the Center for Academic Services, TCU Box 297710, Fort Worth, TX 76129, or at (817) 257-7486. English 30423: Intermediate Composition Course Objectives, Policies, and Syllabus Academic Dishonesty: “An academic community requires the highest standards of honor and integrity in all of its participants if it is to fulfill its missions. In such a community faculty, students, and staff are expected to maintain high standards of academic conduct. The purpose of this policy is to make all aware of these expectations. Additionally, the policy outlines some, but not all, of the situations which can arise that violate these standards. Further, the policy sets forth a set of procedures, characterized by a “sense of fair play,” which will be used when these standards are violated. In this spirit, definitions of academic misconduct are listed below. These are not meant to be exhaustive. I. Academic Misconduct Any act that violates the spirit of the academic conduct policy is considered academic misconduct. Specific examples include, but are not limited to: A. Cheating. Includes, but is not limited to: 1. Copying from another student’s test paper, laboratory report, other report, or computer files and listings. 2. Using in any academic exercise or academic setting, material and/ or devices not authorized by the person in charge of the test. 3. Collaborating with or seeking aid from another student during an academic exercise without the permission of the person in charge of the exercise. 4. Knowingly using, buying, selling, stealing, transporting, or soliciting in its entirety or in part, the contents of a test or other assignment unauthorized for release. 5. Substituting for another student, or permitting another student to substitute for oneself, in a manner that leads to misrepresentation of either or both students work. B. Plagiarism. The appropriation, theft, purchase, or obtaining by any means another’s work, and the unacknowledged submission or incorporation of that work as one’s own offered for credit. Appropriation includes the quoting or paraphrasing of another’s work without giving credit therefore. C. Collusion. The unauthorized collaboration with another in preparing work offered for credit. D. Abuse of resource materials. Mutilating, destroying, concealing, or stealing such materials. E. Computer misuse. Unauthorized or illegal use of computer software or hardware through the TCU Computer Center or through any programs, terminals, or freestanding computers owned, leased, or operated by TCU or any of its academic units for the purpose of affecting the academic standing of a student. F. Fabrication and falsification. Unauthorized alteration or invention of any information or citation in an academic exercise. Falsification involves altering information for use in any academic exercise. Fabrication involves inventing or counterfeiting information for use in any academic exercise. G. Multiple submission. The submission by the same individual of substantial portions of the same academic work (including oral reports) for credit more than once in the same or another class without authorization. H. Complicity in academic misconduct. Helping another to commit an act of academic misconduct. I. Bearing false witness. Knowingly and falsely accusing another student of academic misconduct.” All cases of suspected academic misconduct will be referred to the Director of Composition. Sanctions imposed for cases of academic misconduct range from zero credit for the assignment to expulsion from the University. This policy applies to homework and drafts as well as final papers. English 30423: Rhetorical Practices in Culture Course Objectives, Policies, and Syllabus Unit One Calendar - Getting to Know the Rhetorical Parlor of the 1930s Monday Wednesday Friday 8/22 8/24 8/26 Introduction to 1930s Rhetorical Parlor Decade overview: The Century: America’s Time with Getting Our Bearings: 1930s Cultural Criticism • Kenneth Burke, “Waste--The Future of ProsperPeter Jennings (Volume 2: The 30s) ABC News. ity” 1999. • Helen Keller, “Put Your Husband in the Kitchen” • Assign Rhetorical History 1 8/29 8/31 9/2 Epideictic rhetoric, the 3 appeals Identification and the range of rhetoric Radical epideictic rhetoric • Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s 1st Inaugural Address • Foss, Foss, and Trapp introduction to Kenneth • Keller, “Thoughts That Will Not Let Me Sleep” (Web) Burke • Hughes, “Let America Be America Again” • Kenneth Burke, A Rhetoric of Motives Introduction; • Woody Guthrie “This Land Is Your Land” “Identifying Nature of Property” Last day to choose your parlor figure 9/5 9/7 9/9 Labor Day Holiday The 1930s Literary Wars. Blogging the 30s • Literary Wars handout on eCollege Library Research Meet in Library Room 219 TG 1 Due 9/12 9/14 9/16 John Steinbeck, Harvest Gypsies • Draft of parlor wikipedia page due In Dubious Battle through Ch. 4 In Dubious Battle through Ch. 7 • Parlor figure wikipedia page due with links 9/19 9/21 9/23 In Dubious Battle through Ch. 11 In Dubious Battle through Ch. 13 In Dubious Battle in the parlor • Finish In Dubious Battle • In Dubious Battle reviews • Sample RH1 paper English 30423: Rhetorical Practices in Culture Course Objectives, Policies, and Syllabus Unit One Calendar (continued) Monday Wednesday Friday 9/26 9/28 9/30 On the Left--Michael Gold: • “Proletarian Realism” • “Go Left Young Writer” • “Why I am a Communist” • Sampler of “Red” poems First American Writers’ Congres (1935): • Call for An American Writers’ Congress • Jack Conroy, “Worker as Writer” • Edwin Seaver, “What is a Proletarian Novel?” • Edmund Wilson, “The Case of the Author” Burke vs. Tate • Burke, “Revolutionary Symbolism in America” • Allen Tate, “Poetry and Politics” 10/5 10/7 Harlem Renaissance: Hughes and Hurston • Hughes, “To Negro Writers” “Cora Unashamed” and “The Blues I’m Playing” (Ways of White Folks) • Hurston, “Art and Such” RH1 DUE Assign RH2: Collaborative Multimedia Project • “Passing” (Ways of White Folks) 10/3 Draft of RH1 due for peer review Other important dates 10/12 10/24 11/4 11/11 12/8 12/16 TG2 Due TG3 Due TG4 Due RH2: Collaborative Multimedia Project Due TG5 Due RH3: Rhetorical Analysis Due 8:00-10:30 Final Evaluative Experience