What Teams Want: Team Leadership in the Liberal

What Teams Want: Team Leadership in the Liberal Arts Setting

Karen Berglund, Tyler Kyrola, Kyla Rathjen, and Daniel Sacerio

St. Olaf College

Sociology/Anthropology

Fall Semester 2012

Acknowledgements: A special thank you to Professor Ryan Sheppard and Teacher’s Assistant Charlotte

Bolch for their consistent guidance and support.

Abstract

Recent research shows that there are two types of team leaders that have been found to be most effective: authoritative (one clear decision making leader) and participative (one leader who engages all team members). Additionally, research suggests that women in non-science and technology domains often find females to be unbalanced or inefficient and relate better to male team leaders, though this trend is changing with an increasingly young workforce. We examined further by surveying a random sample of undergraduates from a small liberal arts college in the Midwest and tested the hypotheses: 1)

Female students are more likely than male students to view male leaders as more effective, efficient, and less emotional than female leaders. 2) In small teams (rather than large), students are more apt to prefer free rein and participative leadership over authoritative leadership. Our results indicate that female students hold female leaders in lesser regard than males, and also that authoritative leadership is preferred in large team settings and free rein leadership in small teams.

Review of Literature

Members of the Millennial generation (also known as Generation Y) are entering the workforce at rapid rates (Green and Roberts 2012). These workers currently are and will continue to change the way the workplace functions, in particular concerning working in teams (Gale 2012). Many corporations and businesses struggle with finding ways to adapt to the new expectations and opinions that young workers bring to the workplace, as well as influence these workers with the values already present (Gilbert

2011). Green and Roberts identify four generations populating the workspace at the same time: The

Matures, Baby Boomers, Generation X, and the Millennials. The former two groups generally exhibit a modernist (or traditional) worldview, while the latter two have more postmodern (progressive or liberal) leanings. These non-traditionalist views are even stronger in the Millennials than Generation X individuals. This divided workforce is recognized in research by Sarah Gale (2012) and Cahill and Sedrak

(2012), as well as numerous other researchers and those in the business world. Cahill and Sedrak claim

that members of the Millennials generation (which current undergraduate students belong to) create a workforce that does not value “traditionalist” values of gender stereotypes, racial prejudices, or typical workplace leadership (2012).

As they hold opinions different from previous generations, Millennials entering the workforce in increasing numbers raise questions concerning team member personality, gender, and team cohesion

(Kline and O’Grady 2009); trust and team cohesion (Shin and Song 2010); technology use and cohesion

(Spector and Jones 2004); leadership styles (Cabrera 2009); the importance of feedback within a team

(May and Gueldenzoph 2006); and conflict management in teams (Tjosvold, Hui, Ding, and Hu 2003).

Our research focuses on the desires or expectations that Millennials have for and of their team leaders.

Examining Millennials’ views on various facets of team work dovetails with the general opinion and conception that older generations of workers have of Generation Y: Millennials are inherently team oriented as they have grown up and been educated with team-based learning (Shulte 2012).

Furthermore, Millennials may expect different things from their team leaders than older generations, causing team leaders to not respect young employees and consider them poor workers, and young employees to find business or corporate culture stifling (Green and Roberts 2012). Many workplaces are making efforts to accommodate the opinions of Millennials (Cahill and Sedrak 2012), yet questions still remain as to what exactly these Generation Y workers desire from their job or career.

Expectations for the Workplace

Traditionalist or modernist values relating to leaders and workplace hierarchy place emphasis on bureaucratic management, strong vertical organization (a long chain of bosses or command), directive or authoritative leadership, not questioning the values of the corporation, and work as purely work (not tied up in other values). Non-traditionalist or postmodern values – those which are held and valued by

Millennials – are the opposite and often reflect progressive social trends regarding a decreased faith in authority and viewing social norms as flexible (Green and Roberts 2012). Since there are four generations occupying the workplace at the same time, competition between these clashing worldviews arise as younger workers hold views that do not sit well with older workers or management (Green and

Roberts 2012). Sarah Gale further stresses the importance of building teams and leading in a manner which accommodates both traditionalist and non-traditionalist worldviews (2012).

The beliefs of current undergraduate students may reflect this postmodern or non-traditionalist worldview, which questions the way team leaders and leadership styles, are acted out in the workplace

(Cahill and Sedrak 2012). This creates the potential for dissatisfaction among workers and employers and suggests that there may be expectations or anxieties that Millennials have about acting in workforce teams, including experiencing worldviews vastly differently from their own. Older generations often have biases against Millennials and view them as incompatible with current workplace values, lazy, or falsely entitled (Gavatorta 2012). Adding these biases on top of existing differences between generations and their worldviews (that may or may not be prejudiced against other generations) only creates more possible anxieties for young individuals who are about the enter the workforce (Green and

Roberts 2012). These anxieties or expectations range from team leaders being sexist, leaders only being

concerned with their own personal professional development, and the fear that young workers will not be taken seriously by their older colleagues.

Leadership Styles

Esin Kasapoğlu finds there are six main leadership types: authoritative, task-oriented, participative, achievement-oriented, employee-oriented, and free rein leadership (2011). Authoritative team leaders were defined as very directive and allowing little participation from team members in decision-making processes while maintaining expectations of performance of members. Task-oriented team leaders are those who assign specific tasks and work duties while closely supervising the timeliness of procedures that are assigned. Participative team leaders are those who are approachable, friendly, and participate in work that is assigned to team members. They also consider team members’ suggestions and input when making decisions about the team. Achievement-oriented team leaders are those who prioritize task completion above all else and push long-term achievements as the essential part of the teams’ work. Employee-oriented team leaders are those who are primarily concerned with the human needs of their team members and often take steps to address those needs. Lastly, free rein team leaders are those who maintain a ‘hands-off’ style and consider personal direction as negative. Therefore, they lead by committee and allow team members to make decisions (2011).

Kasapoğlu discovered that two types of leaders are the most effective in his study on Turkish architects: authoritative and participative team leaders. The Turkish architects preferred a strong leader that would guide the team while also being a supportive leader that participates in every aspect of the team. This is reflective of the workplace values of older generations, as the architects studied were not members of

Generation Y (Green and Roberts 2012, Kasapoğlu 2011). These types of strong team leaders will lead and delegate while participating in work and maintain a positive work environment to motivate the success of the team. Coincidentally, Kasapoğlu discovered that free rein leaders, which run a team on the basis of a committee, are not considered effective, as they would hypothetically lead to a chaotic process in the opinion of the participants (2011).

Another study by Chi, Chung, and Tsai also found participative leadership the most effective leadership style. Their research focused on sales teams in Taiwan and how positive moods can enhance motivation, attitudes, and behavior of a successful team (2011). These positive moods are reflective of the participative and employee-oriented team leaders (Kasapoğlu 2011). In their sample of 85 sales teams in

Taiwan, they found positive team leaders to be effective in that they explicitly enhance team performance through motivational, attitudinal, and behavioral team processes. Furthermore, positive team leaders were found to be more participative, effective in maintaining a leadership role, and being approachable while not allowing their positive atmosphere to become a deterrent from effective work

(2011). These findings support Kasapoğlu’s study in that participative leaders often motivate team members to achieve beyond their potential as a successful team as well as maintain the team hierarchy.

Traits and Team Leaders

A developing trend in leadership theory and research is the relationship between personality traits and emergent leadership. Kickul and Neuman (2000) note the importance of viewing leadership as a

dynamic social process and examining how specific individuals become emerging leaders in a team.

Kickul and Neuman placed college students into teams and had them complete surveys regarding traits of the emergent leader in the group. Team performance was then compared to emergent leader traits.

They found that cognitive ability, extraversion, and openness to experience distinguished the leaders from followers in a simulated group setting. Kickul and Neuman (2000) also acknowledged that additional research has shown that verbal skills are predictors of emergent leadership.

Hirschfeld, Jordan, Thomas, and Feild (2008) analyzed U.S. Air Force teams who periodically assessed their teammates via questionnaires. The NEO Five-Factor Inventory (Neuroticism-Extroversion-Openness

Inventory) was the main method of measurement, which is designed to give quick, reliable and valid measures of the five domains of adult personality. The traits measured were: agreeableness, extraversion, conscientiousness, emotional stability, and openness to experience. Extraversion, conscientiousness, and emotional stability were found to be strong indicators of team-leader personalities, whereas high levels of openness to experience only indirectly impacted observed leadership potentials, and therefore were not indicative of team leader personalities (Hirschfeld et al.

2008).

Hirschfeld, Jordan, Thomas and Feild (2008) and Kickul and Neuman (2000) both found extraversion to be a leadership trait. Both studies found two additional leadership traits to extraversion, though different in each study; Kickul and Neuman found cognitive ability and openness to experience; and

Hirschfeld, Jordan, Thomas and Feild found conscientiousness and emotional stability. The different results generated from these studies illustrate the many methods of examining and identifying specific traits that exist in effective leaders.

Gender and Team Leaders

Bhatia and Amati (2010) analyzed the mentoring process for women enrolled in graduate school and the lack of other female mentors in the field of engineering. This mentoring took place both in one-on-one settings and larger team-based settings (2010). Women, an underrepresented group in science, technology, engineering and mathematics fields (STEM) of work, find female mentors and leaders to be much more helpful and open in the graduate setting than male leaders, thus encouraging them to pursue positions in STEM areas and engage in STEM work teams. It is obvious that women are valuable team members in these science fields, as Bear and Woolley state that STEM teams are much more effective and utilize more diplomatic decision-making processes when a balanced gender representation is present (2011). Of course, simply because gender balanced teams are highly effective does not mean that there are not still latent and powerful sexist tones in the workplace (Bear and Woolley 2011).

Women working in fields outside of the STEM domain, however, often relate better to male team leaders than female leaders, finding females to be unbalanced or inefficient in comparison to male leaders (Schieman 2008). Workers and team members of both genders felt comfortable working under a male leader, but women felt high amounts of relational stress when working with a female superior, meaning they felt personally judged by or held back by female leaders (2008). This female team leader stigma may lead to decreased faith in the team’s overall success due to the prejudice that female

leaders embody negative leadership traits. However, an increasingly young workforce is slowly erasing this gap in perception among workers acting in teams (Cabrera, Sauer, and Thomas-Hunt 2009). This stereotyping of male or female leaders has varying levels of effectiveness, but do remain if the field of work in question is heavily dominated by one gender or the other (2009).

Conclusion

To conclude, our literature draws comparisons from several cultures that bring diverse perspectives to the topic of leadership. Since team leadership is such an important component of college academic work, this literature review will be useful when expanding our study, as we will be able to use it as a framework for our research. As the majority of our literature focuses on team leaders in the workplace, we will have to reorient the literature to focus our questionnaire for the undergraduate setting. We see this literature as a strong preparation as we begin to examine what traits and practices are desired in a leader by college students, as well as any future expectations or preferences they may hold. With these observations in mind, we plans on examining the following areas of interest:

Hypothesis 1: Female students are more likely than male students to view male leaders as more effective, more efficient, and less emotional than female leaders.

Hypothesis 2: In small teams (rather than large) students are more apt to prefer free rein, participative leadership over authoritative leadership.

Exploration Question 1: What traits to college students desire in team leaders?

Exploration Question 2: What anxieties and expectations do college students have regarding experiences with team leaders in the workplace (post-college)?

METHODS

Measures

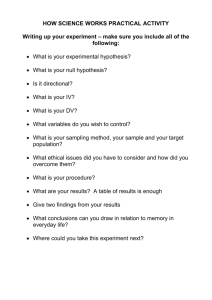

We studied college students’ gender preference of team leaders, students’ preferred leadership styles in small and large teams, students’ preferred traits in a team leader, and students’ expectations of team leadership after college graduation. We surveyed a random sample of students at a small, liberal arts college in the Midwest United States during the fall of 2012. This was executed through an anonymous, online quantitative survey questionnaire with various types of questions such as indexes, multiplechoice, and free-response. Our survey was part of a larger survey created by several other research team exploring the topic of teamwork. Our research tested three hypotheses and was part of a broader survey measuring numerous aspects of classroom and workplace teams, including personal views and preparations for teamwork in future careers.

Variables

Hypothesis 1: Female students are more likely than male students to view male leaders as more effective, efficient, and less emotional than female leaders.

For this hypothesis, the independent variable is gender and its level of measurement is nominal. We determined gender from the demographic section of our survey where we asked respondents which gender they classified themselves under. The response options were “male,” “female,” and “other.” The dependent variable is a 9-item index created to determine if female students are more likely than male students to view male leaders as more effective, efficient, and less emotional than female leaders. The level of measurement for this hypothesis is interval/ratio. The opening question of the index states: “In your experience with classroom teams, is each quality or behavior more typical of male team leaders or female team leaders?” From there, nine statements that expanded on various adjectives describing team leaders were listed, such as: “Letting me know when I have done something poorly is…,” “Acting encouragingly towards members concerning their work on the project is…,” and “Rewarding members for a job well done is…” The response categories consisted of a range of five of Likert scale options:

“Much more typical of male team leaders,” “Somewhat more typical of male team leaders,” “Equally typical of male and female team leaders,” “Somewhat more typical of female team leaders,” and “Much more typical of female team leaders.”

Hypothesis 2: In small teams (rather than large) students are more apt to prefer free rein and participative leadership over authoritative leadership.

For this hypothesis, the independent variable is team size, and its level of measurement is nominal. The dependent variable is leadership styles, and the level of measurement is nominal. The three leadership styles we hypothesized about are defined as follows: free rein leadership as leaders who maintain a

‘hands off’ approach to team leadership and do not heavily engage in personal leadership, participative leadership as leaders who are friendly and approachable while still being bureaucratic and task oriented, and authoritative leadership as strongly bureaucratic and allowing no participation in team decisions from team members (Kasapoğlu 2011). We surveyed this topic using two questions: “When you are part of a small team with few members, which leadership style do you prefer?” and “When you are part of a large team with many members, which leadership style do you prefer?“ The response categories were a list of simplified definitions of each leadership style and the respondent was directed to choose their top two choices. As an indicator of authoritative leadership, we used the description: “A single leader who takes control of the team and is in charge of delegating tasks.” Additionally, as an indicator of participative leadership, we used the description: “A single leader who engages team members and shares responsibility with all team members.” Lastly, as an indicator of free rein leadership, we used the description: “No defined leader, with decisions made equally by all team members.”

Additionally, we explored several other supplementary aspects of leadership. Our first exploratory topic dealt with traits students at our college desire in a team leader. The opening question for this topic was

“Please rate your desire for the following traits in a team leader…” The traits were: “Indecisive,”

“Enthusiastic,” “Perfectionist,” “Communicative,” “Stubborn,” “Conscientious,” “Reliable,” and “Micro-

Managing.” We asked survey participants to respond to a series of Likert scale statements with the following response options: “Very Undesirable,” “Somewhat Undesirable,” “Neutral,” “Somewhat

Desirable,” and “Very Desirable.”

The second exploratory topic dealt with college students’ anxieties and expectations regarding experiences with team leaders in the workplace after graduation. The opening survey question for this

topic was: “For this question, think about team leaders you might have in the future, in your post-St.

Olaf workplaces. Please indicate your level of agreement with each of the following statements. After I graduate and enter the workplace, I believe I will encounter…” The various encounters were listed as,

“Team leaders who are more passionate about their work than team leaders in the undergraduate setting,” “Team leaders who are more concerned with their individual professional development (i.e. promotion or salary) than the team’s success,” “Team leaders who are sexist,” and “Team leaders who underestimate my abilities.” To measure this, we asked all participants to respond by choosing one from a series of Likert scale options. We used the following response categories for each statement: “Strongly

Agree,” “Agree,” “No Opinion,” “Disagree,” and “Strongly Disagree.”

Sample and Sampling

For our research, our target population was the approximately 3,000-member student body at St. Olaf

College, a Lutheran-affiliated private liberal arts college in the Upper Midwest. The student population at this college is predominantly white and composed mainly of students between age 18 and 22. From the target population, we excluded students studying abroad, non-full-time students, students who participated in our focus groups, students currently enrolled in our research methods course, students under the age of 18, and our classroom teaching assistant.

Because of the rule of thumb for sample size recommendations, where a sample size of 30% is used for populations of 1,000 and 10% for populations of approximately 10,000 (Neuman 2012), we sought a sample size between these two of around 25%. To obtain data, we sent an invitation to an electronic version of our survey to a simple random sample of 707 people. We chose a simple random sampling method because of its speed and reliability in gathering a representative sample (Neuman 2012). A simple random sample is an unbiased sampling method in which each individual is chosen randomly from the larger population and has the same probability of being chosen at any stage of the process

(Neuman 2012). The sample was generated randomly via computer from the sampling frame. Susan

Canon, the Director of Institutional Research at the St. Olaf College Review Board, drew our sample and sent them an invitation to our survey via email.

Participation in the survey was voluntary, and we provided incentives for the students asked to participate, in order to increase our response rate. After completing the survey, student participants had the option to enter their name in a drawing for gift certificates to the school bookstore. Ten names were randomly selected, and each individual received a gift card worth $20. In an attempt to increase the response rate, through our response period, we sent a reminder e-mail encouraging participation in our survey.

St. Olaf students received invitations via their email accounts in mid-November, asking them to take our survey online. Prospective respondents had about a week to complete the survey. Out of the 707 invited, 205 people responded, giving us a response rate of 29%. Based on those who responded, 26%

(51) were male and 73% (141) were female. We had responses from students in all classes, with 32% freshman (63), 32% sophomores (64), 16% juniors (31), and 20% seniors (39).

Validity

When writing our survey questions, we recognized the danger of lacking measurement validity, and the failure of operational definitions to reflect conceptual definitions (Neuman 2012). Without assurance that our survey questions actually reflected conceptual definitions, our results could be drastically limited. To account for this, we worked to increase various types of validity in our study. The two main types we were concerned with were face and content validity. Face validity is the extent to which survey questions appear to measure what they are intended to measure, and content validity is whether or not the entirety of a concept is reflected in a question (Neuman 2012). We increased face and content validity by reworking and rewording our survey to fully reflect what we meant in our conceptual definitions of our measures. Many of our questions had to be edited and some had to be thrown out and started over throughout this process, but by testing our questions for validity we have ensured that our survey accurately measured our conceptual definitions (Neuman 2012).

Reliability

We strove to increase the reliability, or consistency, of our measurements as well (Neuman 2012). To ensure that all respondents would understand our questions in the same way, we reviewed previous literature and research relating to topics such as teams, leadership types, and desired leadership traits.

We also conducted a focus group and evaluated how participants discussed these items to get a better feel for how they may be conceptualized by the St. Olaf student body. Our focus group consisted of seven female St. Olaf students who were invited to join us in a discussion about their opinions, experiences, and perceptions of leadership, male and female leaders, and what type of leadership they preferred in small and large teams. We developed our questions for this focus group by discussion within our research team, dialogue with our research professor Ryan Sheppard, and engaging our literature review. Furthermore, by informally pilot testing our survey with our classmates, we were able to see where our questions failed to be consistent in terms of definition and make alterations. Our final draft of survey questions features mutually exclusive and exhaustive responses which assured us that we would not be missing any data simply because we failed to include it in our operational definition.

Ethics

While our survey was anonymous and thus did not inherently pose large risks to participants in terms of social harm from responses (Neuman 2012), we did address some ethical issues to ensure that our study would not put any research participants at risk. These ethical concerns include anonymity, data security, questions of consent, and avoiding at risk populations. The first ethical concern for our study was that of ensuring confidentiality or anonymity to our participants (in this case, anonymity); while our questions did not necessarily probe any obvious sensitive or taboo areas, our participants were kept entirely anonymous to us as researchers so that any responses they provide cannot be traced back to them. This was done through the nature of the survey; once a participant accessed the survey, there was no way to connect one participant’s responses to an actual identity. The anonymous nature of our survey was made clear to participants in the cover letter attached to the survey.

In addition, the raw data of our survey was kept from the public; only the research students and

Professor Ryan Sheppard had any access to raw data. Even though our survey does not handle typically sensitive topics, we focused on wording questions in a way that made any areas of discomfort (such as

sexism or future anxieties) less dangerous or uncomfortable for participants as volatile questions can put participants in uncomfortable or compromising situations (Patton 2011). An implied consent method was used to easily allow those contacted to participate to either do so or opt against so as to allow us to use all responses from those who completed the survey. Furthermore, any participants under 18 years old were not allowed to participate in the study and we did not question other vulnerable populations specifically as they were not included in our sample pool.

We completed and submitted an Institutional Review Board (IRB) application for human subject research as per our institution’s IRB requirements and standards (St. Olaf College Code of Ethics 2010) to ensure all research projects conducted with human participants at our institution do not harm any participants in accordance with ethics codes. Our research was classified as Type 1 research as it was limited to inquiry within our college and did not include vulnerable subjects, a chance of great risk to participants, or any means of identifying research participants. For these reasons, our research application was subject to basic instructor review, completed by Professor Ryan Sheppard.

RESULTS

Hypothesis 1: Female students are more likely than males students to consider male team leaders more effective, efficient, and less emotional than female team leaders.

The independent variable for this hypothesis is the gender of respondent (male or female) and the dependent variable is their score on a Leadership Gender Preference (LGP) index. 141 females (73.4%) and 51 males (24.5%) provided answers to our survey questions. The LGP index first was comprised of nine items yet was cut down to six after removing certain items which failed to fully address our hypothesis or were too vague to yield usable results (such as “encouraging team success”). This six-item

LGP index was used for the majority of our data analysis. The six-item index included items such as

“being overly emotional is…” and “being INeffecient is…” (emphasis in original question). Participants chose between five options on a Likert-scale to express if they felt these qualities were more typical of female or male team leaders (much more typical of female leaders, somewhat more typical of female leaders, equally typical of female and male leaders, somewhat more typical of male leaders, much more typical of males leaders). This allowed us to examine the mean scores within the indices between male and female respondents and gain an understanding of the opinions these groups have about male or female leaders.

Six-Item LGP index scores ranged from 6 to 35 (six items with five choices each), with lower scores meaning the participant felt female leaders were inefficient, ineffective, and highly emotional and males the opposite, and higher scores meaning the participant felt that male leaders were inefficient, ineffective and highly emotional, and females the opposite. We scored each item in the index and summed the scores. The mean score on this index for all participants was 16.93 and the standard deviation was 2.082. Females had a mean of 16.61 and males a mean of 17.5. For the rejected nine-item

LGP index, possible scores ranged from 9 to 45 and had a mean of 25.79 and standard deviation of 2.52.

Table1. Independent Samples T-Test of Nine-Item Leadership Gender Preference Index

Levene’s Test for

Equality of

Variances t-test for Equality of Means

F Sig. t df

Sig. (2tailed)

Mean

Difference

95% Confidence

Interval of the

Difference

Std. Error

Difference Lower Upper

Equal variances assumed

.285 .595 -1.187 110 .

238 -.626 .527

Equal variances not assumed

-1.256 61.171 .214 -.626 .498

Table 2. Independent Samples T-Test of Six-Item Leadership Gender Preference Index

-1.670 .419

-1.622 .371

Levene’s Test for

Equality of

Variances t-test for Equality of Means

F Sig. t df

Sig. (2tailed)

Mean

Difference

95% Confidence

Interval of the

Difference

Std. Error

Difference Lower Upper

Equal variances assumed

2.475 .118 -2.161 112 .

033 -.890 .412 -1.706 -.074

Table 2. Independent Samples T-Test of Six-Item Leadership Gender Preference Index

Levene’s Test for

Equality of

Variances t-test for Equality of Means

F Sig. t df

Sig. (2tailed)

Mean

Difference

95% Confidence

Interval of the

Difference

Std. Error

Difference Lower Upper

.412 -1.706 -.074 Equal variances assumed

2.475

Equal variances not assumed

.118 -2.161 112 .

033 -.890

-2.459 76.011 .016 -.890 .362 -1.611 -.169

Hypothesis 1 is partially supported by our data. An independent samples t-test for the nine-item index comparing mean scores of opinions about characteristics of female and male leaders found no significant difference between male and female respondent opinions (t(-1.187)=110, p>.05), as the mean score for males (m=26.19, sd=2.272) was not significantly different from females (m=25.57, sd=2.574). However, after running an independent samples t-test of our six-item index, we found significance in the responses of male and females (t(-2.161)=112, p<.05) as the mean for males

((m=17.5, sd=1.1566) was significantly different from females (m=16.61, sd=2.113).

We attempted to control for class year by running a Kruskall-Wallis H Test; we felt younger classes with higher response rates may hold stereotypes more strongly than older classes who have taken numerous college courses and may pull the group mean down. However, the Kruskall-Wallis H Test revealed no significant differentiation between class years (Figure 3 and 4).

Table 3. Significance of Kruskall-Wallis H Test Control Test

LGP Index (6-Items)

Chi-square df

Asymp. Sig.

.557

3

.906

Table 4. Kruskall-Wallis H Test Control for Class Year

Class Year

View Male Leaders as Better than

Female Leaders ( 6 Items)

First Year

Sophomore

N

26

41

Mean Rank

58.23

61.04

Junior

Senior

22

31

64.77

58.66

Total 120

Hypothesis 2: In small teams (rather than large) students are more apt to prefer free rein, participative leadership over authoritative leadership.

The independent variable for this hypothesis is team size (small or large) and the dependent variable is leadership style preference. One-hundred-and-forty-one females (73.4%) and 51 males (24.5%) responded. To test this hypothesis we first tested respondent frequencies and created a table (Table 5).

This table demonstrates preferences of leadership style by team size of the respondents. Each leadership style was tested by individually comparing small and large team sizes, which explains why the results add up to more than 100%.

Table 5. Preferred Leadership Style in Small and Large Teams

Preferred in Small Preferred in Large

Authoritative Leadership

Participative Leadership

Achievement-Oriented Leadership

Task-Oriented Leadership

Employee-Oriented Leadership

Teams

19.0%

74.4%

6.3%

13.8%

13.2%

Teams

62.1%

65.5%

21.8%

19.0%

19.0%

Free rein Leadership 63.2% 8.0%

The analysis of the second hypothesis began with focusing on the top three preferred leadership styles, which were Authoritative, Participative, and Free Rein leadership styles. As shown in Table 5, 19.0% of respondents preferred Authoritative leadership in small teams, whereas 62.1% preferred it in large teams. Secondly, 74.4% of respondents preferred Participative leadership in small teams, and 65.5% of respondents preferred it in large teams. Lastly, 63.2% of respondents preferred Free Rein leadership in small teams, and only 8.0% of respondents preferred it in large teams.

We then decided to run a chi-square test of independence to see if there was a statistically significant relationship between the top three leadership styles and preference based on team size. Once the Chisquare-tests had been completed, statistical significance was seen in Authoritative (Table 6) and Free

Rein leadership (Table 7), but not in Participative leadership. Authoritative leadership results showed,

X2=6.476, p=.009. Free rein leadership results showed, X2=8.858, p=.003. Both Authoritative and Free rein had p values that were p<.01, meaning that there is a statistically significant relationship. In contrast, the results for participative leadership showed X2=0.092, p=.761, meaning that there was no statistically significant relationship of students choosing participative leadership based on team size.

Consequently, we were able to claim partial support for our first hypothesis.

Table 6. Chi-Square Test of Authoritative Leadership Preference

Value

Pearson Chi-Square 6.746

Degrees Of

Freedom

1

Asymptotic

Significance

.009

Table 7. Chi-Square Test of Free rein Leadership Preference

Value Degrees Of

Freedom

Asymptotic

Significance

Pearson Chi-Square 8.858 1 .003

After finding that there was a significant relationship between students choosing Authoritative and Free

Rein leadership based on team size, we decided to explore the strength of the relationships. A Cramer’s

V measure of association would be sufficient to identify if there was a strong relationship in the results.

After performing the test for Authoritative leadership style, we found a value of .197 (Table 8). In this context, a relationship of .197 would be considered a weak to moderate. The results for Free Rein leadership style demonstrated a value of .226 (Table 9), which also displays a weak to moderate relationship. This demonstrates that there is partial support for hypothesis 2.

Table 8. Cramer’s V Test for Authoritative Leadership

Value

Nominal by Nominal

N of Valid Cases

Phi

Cramer’s V

.197

.197

174

Approx. Sig.

.009

.009

Table 9. Cramer’s V Test for Free Rein Leadership

Value Approx. Sig.

Nominal by Nominal Phi

Cramer’s V

.226

.226

.003

.003

N of Valid Cases 174

Exploratory Question 1

Our univariate analysis explored the traits that students desire in team leaders. We also examined what college students expect from team leaders when they enter the workplace after college graduation.

When asked to rate their desire for the following traits in team leaders students largely desired enthusiastic (93.7%), communicative (98.2%), conscientious (88.6%), and reliable (92.6%). Students largely found indecisive (89.8%) and stubborn (81.8%) undesirable traits in team leaders. Students were more neutral for the traits perfectionism (34.9%) and micro-managing (31.4%) (Figure 1 and 2).

Figure 1: Student Preference for Perfectionist Trait in Team Leaders (left)

Figure 2: Student Preference for Micro-Managing Trait in Team Leaders (right)

Exploratory Question 2

Our univariate analysis also explored students’ expectations and anxieties concerning team leaders in the workplace after college graduation. When asked to rate their agreement or disagreement with the following statements, students indicated concern about encountering team leaders who underestimate their abilities (68.4% agreed somewhat to strongly), who are sexist (66.3% agreed somewhat to strongly), and who put their individual professional development over the team’s success (79.2% agreed

somewhat to strongly) (Figures 1-3). Additionally, data show that students expect team leaders who are more passionate about their work than team leaders in the undergraduate setting (71% agreed somewhat to strongly).

Figure 3: Student Agreement with Concern about Team Leaders Who Put Personal Success Over Team

Success (left)

Figure 4: Student Agreement with Concern about Sexist Team Leaders (right)

Figure 5: Student Agreement with Concern about Being Underestimated by Team Leaders (bottom)

DISCUSSION

Hypothesis 1

Hypothesis 1 is partially supported by our data, indicating that college females are more likely than their male counterparts to have an adversarial view of female leaders in comparison to male leaders. These findings coincide with portions of our reviewed literature; our results reflect Schieman’s findings that women feel more stress and ill-will towards female leaders than male leaders, while men experience no such increase in stress (2008). Our focus group participants indicated that female leaders were considered inefficient and more unstable than male leaders by female team members, supported by

Cabrera, Sauer, and Thomas-Hunt (2009). We attempted to unveil if these findings were specific to class year, yet a Kruskall-Wallis H Test indicates that these opinions are held statically throughout a college career.

Our findings cannot be used to reject the null hypothesis entirely. A limited index was used to find significance in our data, meaning we cannot assure we are including all aspects of our conceptual definition in our hypothesis. Furthermore, some of the index items may have been polarizing to some participants (i.e. overly emotional) or participants may have felt the need to answer with sociallyexpected results, despite anonymity. The disparity between the number of female and male respondents means we cannot say for certain how the results would have changed if there were more men or less women responding to these questions. We also speculate that males may have been more pressured than females to answer positively about female leaders. Working from the information gathered in our literature review and focus group, our findings do partially support our first hypothesis.

We feel employers, professors, career centers, and students themselves can use our results when it comes to both working under a leader and being a leader. The recognition of long-standing stereotypes in regards to female leaders indicates that female leaders will most likely face more scrutiny than male counterparts in the workforce or academic setting, making it important for employers and educators to make efforts in limiting or eliminating the causes of these stereotypes. Furthermore, our results make it prudent for those appointing leaders or whom have been appointed as a leader to be aware of the gender norms that surround the position and work to subvert them.

Hypothesis 2

While the results for hypothesis 2 have only partial support, employers and college careers centers should find these results incredibly important for their efficiency and success in team cohesion.

Employers would find these results particularly important as students in our research have demonstrated a clear preference in leadership style for certain team sizes. For larger teams students have clearly demonstrated that they would prefer authoritative leadership and for smaller teams, students demonstrated overwhelming support for free rein leadership. This insight will allow employers to create teams that will potentially allow for a more enjoyable team experience that will lead to improved quality of work and efficiency. This insight also is supported by our literature in that free rein is supported in a Western setting (Kasapoğlu 2011).

Furthermore, college career centers can use our findings as a way of assisting students in finding jobs that will allow them to find companies that prefer certain leadership styles within the work groups, such as free rein and authoritative. Lastly, while participative leadership was not a statistically significant finding based on team size, it was clearly the most sought after style when students seek leadership, as was also seen in our literature review (Chi, Chung, and Tsai 2011). This would be important for employers and college career centers to also emphasize the importance of participative leadership.

Exploratory Questions

The results from our univariate analysis of expectations and anxieties about team leaders in the workplace illustrates that students have several anxieties about teams in the workplace after graduation. Our data show that students have anxiety about team leaders being sexist, team leaders who only are concerned with their personal professional development, and team leaders who will underestimate their abilities. Students also expect that team leaders in the workplace post-graduation will be more passionate about their work than they are in the undergraduate setting.

As much literature discusses, these anxieties could be attributed to the conflicting values and biases that derive from generational differences (Green and Roberts 2012). For example, non-traditionalist values are most often held by Millenials, and traditionalist values are most often held by the “Matures” and the

“Baby Boomers” (Green & Roberts 2012). Current St. Olaf students are part of the Millienial generation, whereas team leaders in the workplace potentially will be older and are part of the Baby Boomers or

Mature generations. Multiple scholars recognize this divided, post-graduation workforce as a source of the dissatisfaction and anxieties expressed by young people in workplace teams (Green & Roberts

2012). Based on our data, the anxieties expressed by St. Olaf students reflect these findings from Green and Roberts.

For employers and students entering the workplace after graduation, the results from our univariate analysis provide insight into what students desire in team leaders and what anxieties they have about team leaders in the workplace. Our data indicate that a majority of students desire enthusiasm, communication, conscientiousness, and reliability. Students largely do not desire stubbornness and indecisiveness in team leaders. Our data also revealed no strong indication for a desire or lack of desire for the traits perfectionist and micro-managing. This supports Kickul and Neuman’s discussion of how verbal communication skills are predictors of emergent leadership, among other traits (2000).

Additionally, our findings support Hirschfeld, Jordan, Thomas, and Feild who discuss how conscientiousness is an indicator of team leader personality (2008). It is important to note that from our research, many of the traits students’ desire in team leaders are also many of the traits that are predictive of emergent leaders.

CONCLUSION

Our research examined two hypotheses: if female students are more likely than male students to view male leaders as more effective, more efficient, and less emotional than female leaders; and if in small teams (rather than large) students are more apt to prefer free rein or participative leadership over authoritative leadership. Our research also looked at two exploratory questions, which were the traits

that college students desire in team leaders, and student’s anxieties and expectations regarding team leaders in the workplace post-graduation from college.

Our results for our first hypothesis were partially supported in that college females are more likely than their male counterparts to have a negative view of female leaders in comparison to male leaders. These results demonstrate that females believe that males are more capable of leading a group effectively and efficiently. Our findings show that females maintain stereotypical views of females, specifically that, females are unstable and controlled by emotions. These results would suggest that females in college not only still hold stereotypes of other females, but also would rather be led by their male counterparts.

The results for our second hypothesis, that free rein and participative leadership is preferred over authoritative leadership in small teams (rather than large), was also partially supported. The results show that participative leadership was preferred by all students regardless of team size, but free rein and authoritative were preferred in small and large teams (respectively). Because there was clear support for free rein and authoritative leadership by team size it would be important to structure teams in the future in light of these results.

For our first exploratory question, the results illustrate that students have several anxieties about teams in the workplace after graduation. Students clearly demonstrated anxiety over team leaders being sexist, team leaders who only are concerned with their personal professional development, and team leaders who will underestimate their abilities. For our second exploratory question, the results also illustrate student’s desires in team leaders and what anxieties they expect from team leaders in the workplace. Our data indicate that a majority of students desire enthusiasm, communication, conscientiousness, and reliability and students largely do not desire stubbornness and indecisiveness in team leaders. However, students did not clearly express their desire or distaste for micromanagement and perfectionism.

Considering the results of our research, we recommend that employers and college career centers closely consider our findings. For employers, it is essential to realize that there are still stereotypes that exist about female leaders, even among females. It would be important for human resource departments to focus on trying to end these stereotypes as more women enter leadership positions. For college career centers it would also be important to look at these results, as they should try to have conferences or discussions that can look at ending these stereotypes. Employers will specifically be interested in the results of our second hypothesis, as they will be able to create better teamwork environments based on leadership styles and team size, making teams that work more efficiently and effectively.

College career centers would also find our results of our first exploratory question important, as they would be able to work with students to end students’ anxieties before they enter the workplace.

Furthermore, it will be useful for employers to know the anxieties of students as they enter the workplace, as they can work to end these anxieties before the students enter the workplace. For our second exploratory question, employers would also find it useful as they create teams, as students that will be entering the workplace have clear preferences on leadership traits.

Our sample population, students from a small liberal arts college in the Midwest, limits our ability to take our results beyond students of this college or other similar colleges. Furthermore another weakness is that female respondents dominated our sample. Additionally, our survey length may have discouraged people from taking the survey because of the time it would take to complete. Lastly, as we had a limited amount of time to fulfill our research, our results could not be analyzed to their fullest extent.

For future research, topics of team leadership could be examined in a much more diverse setting and a much less gendered survey sample. We believe that if this research was conducted in larger universities and if the sample was more equal between genders, the results from our research may be much different. In addition, this study could be tested in a workplace setting, which could show further the effectiveness of this study as the results may render more meaningful findings.

REFERENCES

Bear, Julia B and Anita W. Woolley. 2011. “The Role of Gender in Team Collaboration and

Performance.” Interdisciplinary Science Reviews 36(2):146-153.

Bhatia, Shobha and Jill P. Amati. 2010. “If These Women Can Do It, I Can Do It Too: Building Women

Engineering Leaders through Graduate Peer Mentoring”. Leadership and Management in

Engineering 10(4):174-184.

Cabrera, Susan F., Stephen J. Sauer and Melissa C. Thomas-Hunt. 2009. “The Evolving Manager

Stereotype: The Effects of Industry Gender Typing on Performance Expectations for Leaders and Their

Teams.” Psychology of Women Quarterly 33:419-428.

Cahill, Terrance F., and Mona Sedrak. 2012. “Leading a Multigenerational Workforce: Strategies for

Attracting and Retaining Millennials.” F rontiers of Health Services Management 29(1):3-15.

Chi, Nai-wen, Yen-Yi Chung and Wei-Chi Tsai. 2011. “How Do Happy Leaders Enhance Team Success?

The Mediating Roles of Transformational Leadership, Group Affective Tone, and Team Processes.”

J ournal of Applied Social Psychology 41:1421-1454.

Gale, Sarah F. 2012. “Bridging the Great Divide.” PM Network . 26(4):28-35.

Gavatorta, Steve. 2012. “It’s A Millennial Thing.” T+D 66(3):58-65.

Gilbert, Jay. 2011. “The Millennials: A New Generation Of Employees, A New Set Of Engagement

Policies.” Ivey Business Journal 75 (5):26-28.

Green, Daryl D. and Gary E. Roberts. 2012. “Impact of Postmodernism on Public Sector Leadership

Practices: Federal Government Capital Development Implications.” Public Personnel

Management 41(1):79-96.

Hirschfeld, Robert R., Mark H. Jordan, Christopher H. Thomas and Hubert S. Feild. 2008. “Observed

Leadership Potential of Personnel in a Team Setting: Big Five Traits and Proximal Factors as

Predictors.” International Journal of Selection and Assessment 16(4):385-402.

Kasapoğlu, Esin, 2011. “Leadership Behaviors in Project Design Offices.” Journal of Construction

Engineering & Management 137(5):356-363.

Kickul, Jill and George Neuman. 2000. “Emergent Leadership Behaviors: The Function of Personality and

Cognitive Ability in Determining Teamwork Performance and KSAs.” Journal of Business &

Psychology 15(1):27-51.

Kline, Theresa J.B and James K. O’Grady. 2009. “Team Member Personality, Team Processes and

Outcomes: Relationship Within a Graduate Student Project Team Sample.” North American Journal of

Psychology 11(2):369-82.

May, Gary L. and Lisa E. Gueldenzoph. 2006. “The Effect Of Social Style On Peer Evaluation Ratings In

Project Teams.” Journal Of Business Communication 43(1):4-20.

Schieman, Scott and Taralyn McMullen. 2008. “Relational Demography in the Workplace and Health: An

Analysis of Gender and the Subordinate-Superordinate Role-Set.” Journal of Health and Social

Behavior 49:286-300.

Schulte, Margaret F. 2012. “The Millennials: Challenges, Opportunities, and Promise.” Frontiers of Health

Services Management 29(1):1-2.

Shin, Yuhyung and Kyojik Song. 2010. “Role of Face-to-Face and Computer-Mediated Communication

Time in the Cohesion and Performance of Mixed-Mode Groups.” Asian Journal of Social

Psychology 14:126-139.

Spector, Michelle D. and Gwen E. Jones. 2004. “Trust in the Workplace: Factors Affecting Trust

Formation between Team Members.” Journal of Social Psychology 144(3):311-321.

St. Olaf College 2010. “Who Needs to Review My Project?” Northfield, MN: St. Olaf College. Retrieved

December 3, 2012. http://www.stolaf.edu/academics/irb/Policy/WhoReviews.pdf

Tjosvold, Dean, Chun Hui, Daniel Z. Ding, and Junchen Hu. 2003. “Conflict Values and Team

Relationships: Conflict’s Contribution to Team Effectiveness and Citizenship in China”. Journal of

Organizational Behavior 24:69-88.