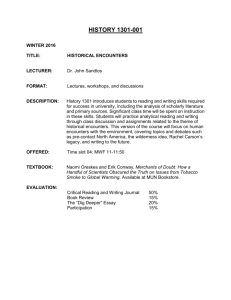

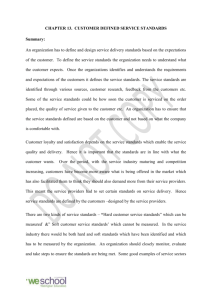

designing unified service encounters - Aaltodoc - Aalto

advertisement