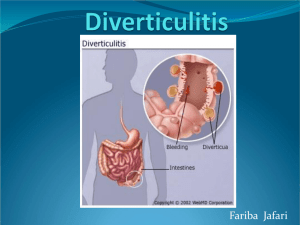

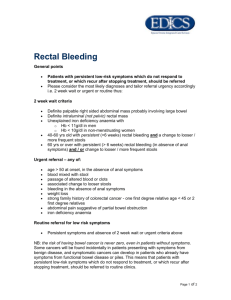

COLON & RECTUM

advertisement