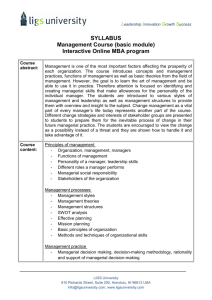

Conceptual Framework for Managerial Costing

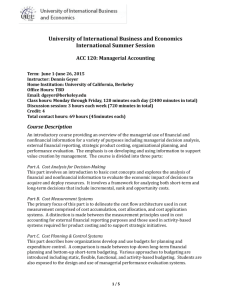

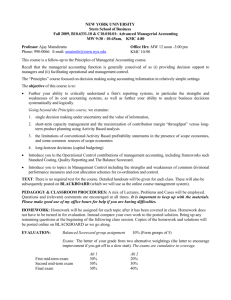

advertisement