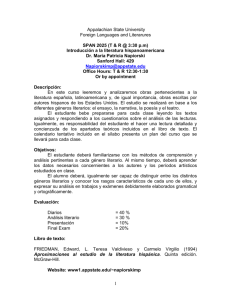

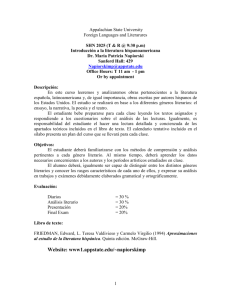

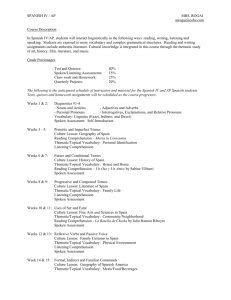

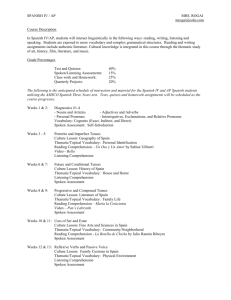

Artículo completo

advertisement