Topic 1 – Neolithic Overview - Northumberland National Park

advertisement

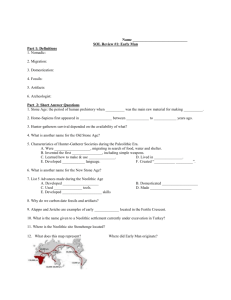

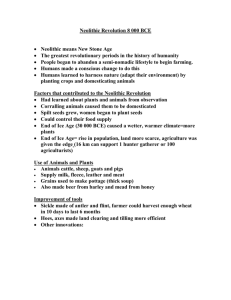

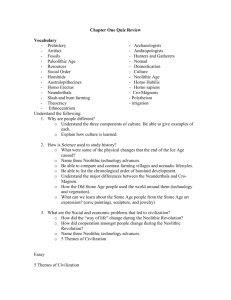

TOPIC ONE: PREHISTORIC LANDSCAPES – THE NEOLITHIC PERIOD LEARNING OBJECTIVE To introduce children to the Neolithic period using specific landscapes and sites in the Northumberland National Park and North Pennines as local case studies RESOURCES Powerpoint Slides Photographs Maps Activity Sheets Artefact Collection CURRICULUM LINKS KS 2 History: Changes from the Stone Age to the Iron Age KS 2 Science, Maths, Art and Design, English. (See Activity Sheets for detailed links) LEARNING QUESTIONS 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. What does “Neolithic” mean? When was the Neolithic period? What was Neolithic life like in our area? What was Neolithic technology like? What Neolithic features are in our region? RELATED ACTIVITY SHEETS – NEOLITHIC LIFE AND TECHNOLOGY Artefact Investigation The String Revolution – Neolithic plant-based technology The Sum of its Parts – Compound tools technology Pottery Throughout Prehistory What Does Rock Art Mean? Make some Megaliths End of Topic Review: Do “Archaeology Detective” or “Who’s Who in Prehistory” activities, focusing on Neolithic evidence. End of all Topics Review: Do “Out of Order Story” focussing on all periods. 1 LEARNING QUESTIONS: LEARNING QUESTION 1: WHAT DOES “NEOLITHIC” MEAN? The Neolithic period is part of prehistory – “before history” or before written records. Neolithic means “New Stone Age”, from the Greek words Neo (new) and Lithos (stone). Basically this describes the appearance of a new way of making stone tools – Neolithic tools include very fine flaked, polished and ground stone tools and large blades. The flaking methods used seem to show that the tool makers were trying to make the most of the stone and avoid waste. This is a subdivision of the Three Age System (Stone Age, Bronze Age, Iron Age): the Stone Age includes the Palaeolithic (Palaeo = old) and Mesolithic (Meso = middle). The Three Age system was developed by Danish museum curator and antiquarian Christian Jürgensen Thomsen (1788-1865) in 1816-1819, to order the collections of artefacts from oldest to newest. Sir John Lubbock (1834-1913), the first Baron Avebury, later divided the Stone Age into the Palaeolithic and Neolithic periods, in his 1865 book Prehistoric Times. Archaeologist Hodder Westropp (d. 1884) introduced the idea of the Mesolithic in 1866. Archaeologists have tinkered with this system and created many local versions, subdivisions and revisions, but it’s still a useful way of thinking about the past. The Neolithic period in Britain is also defined by changes in how people lived. Not only did they use different types of stone tools but they gradually adopted a different lifestyle involving farming and settled life. In some parts of the world this change is called “the Neolithic Revolution”, because it involved very big changes in how people lived. However, these changes probably took place over many generations, so it might not have seemed like a dramatic “revolution” to the people living at the time. The climate, plants and animals in Britain also changed. (See What was Neolithic life like in our area? for more information). LEARNING QUESTION 2: WHEN WAS THE NEOLITHIC PERIOD? The Neolithic period in Northumberland dates from approximately 4,000 BC to 2,000 BC. The Neolithic period lies after the Mesolithic period (from the end of the last glaciations up to approximately 4000 BC) and before the Bronze Age (from 2000BC to approximately 700BC). The Neolithic is sometimes divided into the Early Neolithic (from 4000 to 3200 BC) and the Later Neolithic (3200 to 2500 BC). 2 LEARNING QUESTION 3: WHAT WAS NEOLITHIC LIFE LIKE IN OUR AREA? The Neolithic period in Britain started around a thousand years later than the Neolithic period on the Continent. Mesolithic Britons may have been aware of farming for a long time before they decided to start doing it. The period preceding the Neolithic was called the Mesolithic, or “middle stone age”. Mesolithic people lived in small groups, hunting, gathering food, fishing, and travelling to different places at different times of the year, building temporary camps close to seasonal resources. They didn’t have farms but would encourage useful plants to grow by clearing away other vegetation and coming back to the area over the years. Some archaeologists think that there was not a dramatic change from the Mesolithic to the Neolithic in our region. Neolithic people probably still moved around the landscape during the year. In the summer, they may have grazed their cattle on the fell sandstone landscapes, like Lordenshaws, and also kept pigs and perhaps sheep or goats. They probably had small plots for growing crops, like emmer wheat, barley and oats, on gravel terraces and parts of the lower Cheviot slopes. People gradually started living a more settled lifestyle – they built more permanent homes, cleared trees to make fields for crops and grazing land for their livestock. However they still lived at least part of the year in different locations, and still got some of their food from hunting, fishing and gathering. Their prey would have included wild cattle or aurochs (a very large and fierce sort of wild cattle), red deer, wild boar, other small mammals, fish and birds. Some food, such as grain and nuts, was stored in pits dug into the ground. People made cheese from milk, and beer from grain, and stored it in clay pots. Other archaeologists think that as groups became more settled, and tied to the land through farming, their way of thinking would have changed a great deal. For perhaps the first time, people would have had the idea of “owning” land and resources, and this could have led to conflict between different groups. For example, arrowheads become very common in the early Neolithic and may have been used in warfare as well as hunting, as many have been found at enclosure entrances, like at Crickley Hill in Gloucestershire, and even lodged in human skeletons (Waddington and Passmore 2004). People were definitely more settled by the Later Neolithic period. The North Pennines and Northumberland Uplands region also contains many striking Neolithic monumental sites: large earthworks, tombs, barrows, cairns and stone arrangements. Archaeologists think these were special ceremonial places. Barrows and cairns were used for burial, and many bodies would be buried together. Tombs would be opened up to add new burials. Archaeologists think this shows that Neolithic people wanted to connect their communities to their landscape, by burying everyone together in a visible place – everyone was equal in belonging to the countryside. The “ancestors” and the landscape would be connected. People would visit these monuments to worship and 3 celebrate, but also to do everyday activities like trading and sharing news. There probably wasn’t a distinction between “ritual” and “everyday life” like we have today. Social changes in the Neolithic also included the development of social groups beyond the family – that is, of communities who worked together to build these large monuments. Some archaeologists think that a social elite would have arisen to lead their communities in these big cooperative projects. However we do not know if these leaders were hereditary chieftains, priests or tribal councils (Waddington and Passmore 2004). It seems likely that the social changes which took place in the Neolithic period played out in different ways in different areas. Peoples’ culture and ideas, as well as the resources in their local area, would have made them make different choices in how to live their lives: some groups may have been very settled, while others preferred to move around throughout the year. LEARNING QUESTION 4: WHAT WAS NEOLITHIC TECHNOLOGY LIKE? Stone Tools: Neolithic technology was based around tools made of stone (which are the most obvious and frequently-surviving items) but also many other types of materials. Stone tools included delicate retouched stone arrowheads, polished stone axe heads, stone blades and grindstones. Retouching, grinding and polishing were techniques developed in the Neolithic to make very fine, sharp and simply beautiful stone tools. Many stone axes discovered around Milfield and Rothbury (near Lordenshaws) came from Langdale in the Lake District, Cumbria. Flint nodules were also imported from areas with chalk geology in the south. These imported materials show that Neolitihic people had long-distance trading networks. Although axe-heads and arrowheads are tools, they also probably had important symbolic value. For example, stone axe-heads were often deposited as offerings in ditches, pits and burial cairns. In the Later Neolithic, stone tool design shifted to flake-based technology for everyday tools, while beautiful high-quality arrowheads, chisels, axes, daggers, maces and carved stone balls were made as trade or luxury items. Pottery: The Neolithic period saw the first pottery used in Britain. Clay becomes pottery when fired to 500-600C. These temperatures can be reached in an open fire, without the need to build a kiln. The earliest pottery was not very high quality and doesn’t survive very well in archaeological sites. Pottery objects would not have been very convenient for people with a very mobile lifestyle, such as in the Mesolithic, but as people became more settled pottery came into its own in food storage and cooking. Early Neolithic pottery types include Grimston Ware, Peterborough Ware and Grooved Ware. Some archaeologists think that the distinctive “bag” shape of Grimston Ware comes from the early potters copying the shape of leather bags (Waddington and Passmore 2004: 53). Other pottery types, such as Grooved Ware, get their name from their decorations, made by scratching shapes into the wet clay 4 with animal teeth, sticks, or shells; making impressions with coils of string; making shapes with their fingernails. Shelter: Sites at Thirlings, in the Milfield Basin, and near Bolam Lake, have been excavated showing post-holes that were probably for temporary camps. Archaeologists found trapezoidal and triangular arrangements of stone-packed postholes, with small stakeholes situated around themhh. These may have supported tents with wooden poles, and perhaps covered with animal skins. People built stronger homes for winter, which are known to archaeologists as roundhouses. They probably had stone or earth walls, a roof made of wooden beams and with heather thatch, or even turf. People may have had to rebuild their homes a few times – there are examples of excavated sites showing roundhouse foundations overlapping each other, showing that people came back and built in the same place. Monuments: Large (and small!) monuments like cairns, barrows, stone circles and enclosures were made by digging ditches, piling up earth to make banks, and moving large stones into place. Some of the stones had been brought from far away – people may have dragged them using rope, or put them on log rollers to help transport them. No Neolithic shovels have been found in our region, but the remains of a wooden shovel have been found in the Vale of Pickering (North Yorkshire), and in other places the shoulder blades of elk or deer were used. Cairns (including Long Cairns and Round Cairns) are made out of local stone – a small stone coffin or cist was made by digging a straight-sided hole and lining it with slabs of flat stone, with another flat stone for a lid, and the whole thing was then covered with a big pile of stone and earth. Some of the large hilltop Round Cairns, such as at Simonside, may also be Neolithic (though they are often attributed to the Bronze Age). Another important monument type is the Neolithic rock art. The rock art was made by scratching, grinding or pecking “cups” (circular depressions) and “rings” (circles surrounding the cups) into natural outcrops of stone such as the fell sandstone at Lordenshaws. In the later Neolithic cup-marked stones were incorporated into other monuments such as stone circles and henges. The designs had meaning to Neolithic people, but we can’t interpret that meaning today. Other items: Neolithic people probably used many more objects made of wood, bark, leather, fleece, string and other perishable materials than of stone – but these materials do not survive for very long so we do not have many examples. Many people known from history who used stone tools had them as only a tiny part of their sophisticated everyday toolkits – they used wood, bark, feathers, animal skins, shells, bones, teeth, berries or seeds, string made from human hair, animal tendons and plant fibres, and decorated themselves and their possessions with dyes and paints made from insects, plants, minerals and charcoal. Although we’ll never know for sure, it might be that Neolithic people in this part of the world looked very different from how we imagine! 5 Some early metal artefacts were also made towards the end of the Neolithic. The idea of how to melt ore to make metal objects may have been brought over by travellers from the Continent and slowly spread up to this region. LEARNING QUESTION 5: WHAT NEOLITHIC FEATURES ARE IN OUR REGION? There are many Neolithic features surviving in the landscape of Northumberland National Park. These include rock art, causewayed enclosures, henges, cursus and some stone circles. Northumberland’s stone circles are generally much smaller than those in the south. LORDENSHAWS AND SIMONSIDE ANCIENT LANDSCAPE, NORTHUMBERLAND NATIONAL PARK Lordenshaws and Simonside is a multiperiod ancient landscape in the Northumberland National Park, a short drive south of Rothbury. It contains features from the Neolithic, Bronze Age and Iron Age as well as medieval and modern farming remains. The best-known Neolithic features at Lordenshaws are the rock art panels, accessible from the National Park car park on the north side of the road. The exact date when these panels were carved is not known but many archaeologists think they are from the Neolithic period, and may have continued into the early Bronze Age. The rock art is carved into the Fell Sandstone. The art motifs cannot be interpreted – they are abstract designs, showing cups and rings scraped or pecked into the stone, rather than pictures of animals or people. The circle is a common motif in art all over the world. There are numerous theories about the rock art’s meaning but the most important question which needs to be answered is about chronology. When we discover exactly when the rock art was made we can look at how it fits in with other changes in archaeology. For example, there might be links between cup and ring marks and certain designs of Neolithic arrowheads and ceramic styles (Waddington 2006). The reuse of rock art is another important line of enquiry. It appears that cup and ring marked art was first made on natural outcrops of exposed rock, and then these carved rocks were later incorporated into other Neolithic ceremonial monuments including long cairns, stone circles, standing stones and henges. By the early Bronze Age they were specifically included in burial monuments (Waddington 2006). Changes in the use of rock art could indicate bigger changes in the way people thought and lived throughout prehistory. (This is covered further in the Bronze Age and Iron Age topics). It is also useful to consider rock art in its landscape context. Some questions to consider: why are there carvings on the lower slopes of Lordenshaws but not up high on Simonside, when the same stone is available in both places? What landscape features are near Lordenshaws? (The bedrock is very close to the surface in this area so it is possible that, even when the region was wooded, there may have been a natural clearing around the 6 Main Panel and other large stones – these might have been useful landmarks or stopping points for travelers?). The Simonside ridge on the south side of the road is the highest point in the fell sandstone landscape of the Simonside Hills, part of the Cheviot Hills. This landscape contains many remnants of prehistoric activity (see Bronze Age and Iron Age topics for further information). On the Simonside Ridge, a fairly short walk uphill along the path from the National Park carpark, are the remains of several large cairns. These have been identified as Bronze Age burial cairns but some may have been established in the Neolithic period. Resources for excursions: Students may use smart phones to follow the Rock Art on Mobile Phones tour or download maps and references beforehand to use on their phones or other mobile devices when exploring the landscape at Lordenshaws. Visit the website here: http://rockartmob.ncl.ac.uk/ Park at the National Park car park between Simonside and Lordenshaws (signposted off the B6342 south of Rothbury, follow the brown tourist information signs to Rothbury). Additional parking, picnic tables and trees for shade are available in the Forestry Commission car park, a 5 minute drive further down the same access road. The nearest public toilets and shops are at Rothbury, a 10 minute drive further north along the B6342. Please refer to the Lordenshaws Excursion Hazard Identification sheet included in this education pack for known hazards, nearby facilities and tips for arranging a site visit. FURTHER READING AND RESOURCES LIST: BOOKS, ARTICLES AND DOCUMENTARIES Introductions to Archaeology Adams, Simon 2008. Archaeology Detectives. Oxford University Press: Oxford Deary, Terry 2008. The Savage Stone Age (Horrible Histories). Scholastic: London. Ganeri, Anita 2014. Life in the Stone Age, Bronze Age and Iron Age (A Child’s History of Britain). Raintree: Basingstoke. Hibbert, Claire 2014. The History Detective Investigates: Stone Age to Iron Age. Wayland: Hachette Children’s Books. 7 Many more books are listed at Best Books About Archaeology For Kids page on the Best Children’s Books.org [website] URL: <http://www.the-best-childrensbooks.org/archaeology-for-kids.html> Accessed 15th August 2014 Rock Art in Northumberland Ayestaran, H., G. Bailey, S. Beckensall, G. Goodrick, M. Johnstone, J. Kemp, A. Mazel and C. Waddington 2004. Rock Art Project: Northumberland Rock Art – Web Access to the Beckensall Archive. [online] Available at: < http://rockart.ncl.ac.uk/> [Accessed 14/7/2014]. Beckensall, Stan 1974. The Prehistoric Carved Rocks of Northumberland. Newcastle: Frank Graham. Beckensall, Stan 1983. Northumberland’s Prehistoric Rock Carvings. Rothbury: Pendulum Publications. Beckensall, Stan 2003. Prehistoric Northumberland. Stroud: Tempus. Beckensall, Stan 2009. Prehistoric Rock Art in Britain. Stroud: Amberley Publishing. Bradley, R. 1991. Rock Art and the Perception of Landscape. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 1(1):77-101. Fairén-Jiménez, S. 2007. British Neolithic Rock Art in its Landscape. Journal of Field Archaeology 32(3):283-295. Mazel, A., A. Galani, D. Maxwell and K. Sharpe 2012. ‘I want to be provoked’: public involvement in the development of the Northumberland Rock Art on Mobile Phones project. World Archaeology 44(4):592-611. Waddington, C. 1998. Cup and Ring Marks in Context. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 8(1):29-54. Waddington, Clive 2006. Rock Art, in: Petts, David and Christopher Gerrard eds, North-East Regional Research Framework [.pdf]. URL: <http://content.durham.gov.uk/PDFRepository/NERFFBook2.pdf > Accessed 1st January 2014 Prehistory in Northumberland and the North Pennines Frodsham, Paul 2004. Archaeology in the Northumberland National Park. Council for British Archaeology: York. 8 Frodsham, Paul 2006. In the Valley of the Sacred Mountain: an introduction to prehistoric Upper Coquetdale 100 years after David Dippie Dixon. Northern Heritage: Newcastle Upon Tyne. Waddington, Clive & David Passmore 2004. Ancient Northumberland. Country Store: Wooler. Young, Robert, Paul Frodsham, Iain Hedley and Steven Speak 2004. An Archaeological Research Framework for Northumberland National Park: Resource Assessment, Research Agenda and Research Strategy – Section 4, Prehistory [.pdf] URL: <http://www.northumberlandnationalpark.org.uk/understanding/historyarchaeology/archa eologicalresearchframework > Accessed 1st January 2014 Neolithic Britain and Europe BBC 2003. Britain BC, a Channel 4 documentary based on Frances Pryor’s book of the same title. Brown, N. Neale, and R. Francis (2011) Peak into the Past: An Archaeo-Astronomy Summer School. School Science Review (342). pp. 83-90. Burl, Aubrey2005. Prehistoric Stone Circles (Shire Archaeology). Shire Books. Burl, Aubrey 2008. Prehistoric Henges (Shire Archaeology). Shire Books. Cope, Julian 2011. The Modern Antiquarian: A Pre-Millennial Odyssey Through Megalithic Britain: Including a Gazetteer to Over 300 Prehistoric Sites. Thorsons. Cunliffe, Barry 2013. Britain Begins. Oxford University Press: Oxford. Deary, Terry 2008. The Savage Stone Age (Horrible Histories). Scholastic: London. English Heritage 2011a. Introductions to Heritage Assets: Prehistoric Avenues and Alignments [.pdf] URL: < https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/publications/iha-prehistoricavenues-alignments/prehistoricavenuesalignments.pdf > Accessed 12th February 2014 English Heritage 2011b. Introductions to Heritage Assets: Prehistoric Henges and Circles [.pdf] URL: < https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/publications/iha-prehistoric-hengescircles/prehistorichengesandcircles.pdf > Accessed 12th February 2014 English Heritage 2011c. Introductions to Heritage Assets: Prehistoric Barrows and Burial Mounds [.pdf] URL: < https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/publications/iha-prehistoricbarrows-burial-mounds/prehistoricbarrowsandburialmounds.pdf > Accessed 12th February 2014 9 English Heritage 2011d. Introductions to Heritage Assets: Prehistoric Rock Art [.pdf] URL: < https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/publications/iha-prehistoric-rockart/prehistoricrockart.pdf > Accessed 12th February 2014 Lynch, Frances 1997. Megalithic Tombs and Long Barrows in Britain (Shire Archaeology). Shire Books. Thomas, Julian 1999. Understanding the Neolithic. Routledge Pollard, Joshua 2002. Neolithic Britain. (Shire Archaeology). Shire Books. Pryor, Francis 2003. Britain BC: Life in Britain and Ireland before the Romans. Harper Collins: London. WEBSITES BBC 2014. BBC History: British Prehistory [website] URL: < http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/british_prehistory/> Accessed 20th July 2014 British Museum 2014a. The Portable Antiquities Scheme [website] URL: <www.finds.org.uk > Accessed 20th June 2014 This is the website of the Portable Antiquities Scheme. People who find archaeological artefacts by accident or through metal-detecting are encouraged to report their discoveries to this Scheme so that others can use the information. Searching this website by region and historic period allows you to see what archaeological finds have been reported in your area. British Museum 2014b. Neolithic Britain School Image Bank [website] URL: < https://www.britishmuseum.org/learning/schools_and_teachers/resources/all_resources1/neolithic_britain.aspx > Accessed 20th June 2014 Cope, Julian 2014. The Modern Antiquarian [website] URL: < http://www.themodernantiquarian.com/home/> Accessed 11th January 2014 Council for British Archaeology 2013. The Young Archaeologists’ Club: Leaders’ Area – Activity Ideas. URL: < http://www.yac-uk.org/leaders/ideas > Accessed 12th January 2014 Very useful list of archaeology-related activities for 8 to 16 year olds. Durbin, Gail, Susan Morris and Sue Wilkinson 1992. Learning from Objects: A Teacher’s Guide. English Heritage: London. Now made freely available as a .pdf as part of an ongoing digitization project to make previously published information about English Heritage properties accessible to teachers. URL: <http://www.tes.co.uk/teaching-resource/Learningfrom-Objects-a-teacher-s-guide-6059739/ > Accessed 15th July 2014 10 English Heritage 2014. PastScape [website] URL: <http://www.pastscape.org.uk/ >Accessed 10th February 2014 This website allows you to search by location and historic period to find ancient monuments in your area, and provides links to further information. The Megalithic Portal 2014. The Megalithic Portal [website] URL:<http://www.megalithic.co.uk/ > Accessed 10th January 2014 Northumberland County Council 2014. Keys to the Past [website] URL: <http://www.keystothepast.info/> Accessed 12th January 2014 Northumberland National Park 2014. The Northumberland National Park site [website] URL: <www.northumberlandnationalpark.org.uk > Accessed 20th June 2014 Visiting the Northumberland National Park website and searching for “Neolithic”, “archaeology” and “The Ancients” plus the names of specific sites mentioned in this education pack will bring up more information. RAMP 2014 The Rock Art on Mobile Phones Project [website] URL: <http://rockartmob.ncl.ac.uk/ > Accessed 12th January 2014 Tyne and Wear Museums 2014a, The Great North Museum Hancock [website] URL: < http://www.twmuseums.org.uk/great-north-museum.html > Accessed 10th March 2014. Many of the artefacts photographed for the slides accompanying this education pack are on display at the Great North Museum Hancock. Additional educational materials are available to download from their website. Contact the museum for information on activity materials that can be borrowed to use on a visit to the museum. Tyne and Wear Museums 2014b, Boxes of Delight Artefact Loan Programme [website] URL: < http://www.twmuseums.org.uk/schools/boxes-of-delight/find-boxes.html > Accessed 10th August 2014 The Tyne and Wear Museums offers free loan of handling collections of artefacts, including a Celts and Romans collection. Please contact the museum through the above website for more information. 11