Module 6: The Business Cycle and Government Policy

advertisement

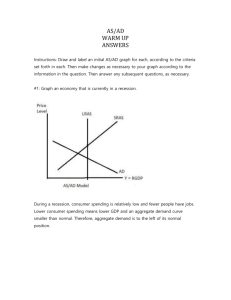

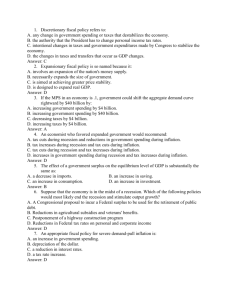

Module 6: The Business Cycle and Government Policy Mankiw Chapter 15 (Aggregate Supply and Demand) and Mankiw Chapter 16 (Fiscal and Monetary Policy) Introduction Market economies have always been subject to the boom and bust of the BUSINESS CYCLE. Modern macroeconomics was born in the greatest economic downturn of the last 100 years, the Great Depression of the 1930s. More recently, the Great Recession of 2007-2009 stirred new controversy and revived old debates within the economics profession as to whether and how the government should respond to such crises. The Classical model of inflation and output that we studied in the last three modules does a good job of explaining the long run behavior of the macroeconomy, but it does not explain the business cycle well. In the Classical model, real GDP is determined by the number of workers and their productivity. Nominal variables such as the money supply and the price level (M and P) have no effect on real GDP or real economic well-being in the Classical model. In this module we’ll introduce an alternative model in which nominal variables such as P and M do affect real variables such as unemployment (U) and real GDP (Y) in the short run. In the long run, we’ll see, the AS/AD model is consistent with the Classical model. In the first half of this module we will describe the business cycle and its characteristics, and then sketch out the theory of Aggregate Supply (AS) and Aggregate Demand (AD). We’ll also show how this short-run “Keynesian” AS/AD model of the business cycle is consistent with the long-run Classical model. In the second half of this module we will use the AS/AD model to explain how government fiscal policy (spending and taxation) and monetary policy might be used to “stabilize” (reduce the severity) of the business cycle. Finally, we will explore the pros and cons and difficulties of implementing stabilization policies. Three Facts About the Business Cycle The Business Cycle is the short-term fluctuation of real GDP, unemployment, and other economic variables around their long term trend. It is the cycle of boom and bust that characterizes economic activity in a market economy. The National Bureau of Economic Research recognizes 32 full cycles of the U.S. economy since 1857, averaging about five years in length (see http://www.nber.org/cycles/cyclesmain.html for the full list). There are three basic facts that I want you to know about the business cycle. 1) The Business Cycle is irregular and hard to predict. Usually when we think about cycles we think of regular cycles, such as the phases of the moon or the passing of the seasons. The Business Cycle is not like that. Instead, it’s irregular and very difficult to predict. Figure 6.1 shows the quarterly percentage changes in U.S. nominal GDP since World War II. The gray bars indicate recessions. As you can see, the times between the gray bars are variable, and the rate of change in GDP varies abruptly. Over the past 100 years, business cycles have ranged from less than two to more than ten years in length. 2 Figure 6.1: Growth Rates of U.S. GDP, 1947 – 2010 Source: St. Louis Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED2) 2) Unemployment rises when GDP falls. The negative relationship between GDP and unemployment makes a lot of sense, if you think about it. GDP is a measure of the production of goods and services. Businesses produce goods and services using labor. When output falls, fewer workers are needed, and more people become unemployed. It’s a very strong relationship, as you can see in figure 6.2 below, which shows the annual percentage change in GDP (blue) plotted along with the unemployment rate (red). When one rises, the other falls, pretty much. Figure 6.2: GDP growth rates and Unemployment Rates, 1947-2010. Source: St. Louis Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED2) 3 3) Many economic variables move together. Here’s a picture of annual percentage changes in GDP (blue) since 1929, along with changes in two other economic variables: private Investment (green) and federal government tax receipts (red). You can see that the three variables move together, and that investment and tax receipts are very sensitive to GDP changes. Most other economic variables move with the business cycle, including retail sales, car miles driven, loans, stock market prices, and inflation rates. Figure 6.3: Government Tax Receipts (red), GDP (blue), and Investment (green), 19292010 Source: St. Louis Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED2) That’s why the business cycle is so important. It affects nearly everything. Explaining the Business Cycle’s Short-Run Fluctuations Aggregate Supply and Demand. We can summarize the short run relationship between the aggregate price level (P) and real GDP (Y) using a model of Aggregate Supply (AS) and Aggregate Demand (AD), as shown in figure 6.4 below. “Aggregate” means “formed by a combination or collection of many separate units.” The aggregate price P on the vertical axis is a price index P such as the CPI or the GDP Deflator. The aggregate quantity Y on the horizontal axis is aggregate output, or real GDP. 4 Figure 6.4: Aggregate Supply and Aggregate Demand The Aggregate Demand Curve shows the relationship between the price level and the quantity of goods and services that households, firms, government, and foreigners wish to buy. There are four components of Aggregate Demand: Y = C + I + G + NX. The Aggregate Supply Curve shows the relationship between the price level and the quantity of goods and services that firms choose to produce and sell. The macroeconomy is in equilibrium when desired spending equals desired production. We will manipulate the Aggregate Supply and Aggregate Demand model the same way that we manipulate an ordinary microeconomic supply and demand model for a single good such as peanut butter: Given an event, we’ll ask 1) Which curve shifts? 2) Which way does it shifts?, and 3) What happens to price and real GDP (and, therefore, unemployment)? But before we can manipulate the AS/ AD model, we need to understand why the AS and AD curves slope the way they do, and what makes them shift. The Aggregate Demand Curve: YD = C + I + G + NX Why does the AD Curve Have a Negative Slope? A negative slope to AD means that if the price level rises desired spending falls. Since desired spending is composed of desired consumption (C), investment (I), government spending (G), and net exports (NX), desired spending will fall if C, I, G, or NX falls. Government spending G is driven by politics, and is not 5 affected much by prices. That gives us at least three possible reasons why the Demand Curve might have a negative slope: 1) P C (The Wealth Effect): Some of consumers’ wealth is in the form of money, which becomes less valuable as P rises, making consumers poorer. Poorer people consume less. In symbols, we write: P Wealth C (GDP demanded), so AD has a negative slope. 2) P I (The Interest-Rate Effect): When price levels rise, people need to hold more cash for transactions purposes, since prices are higher. To get more cash they will borrow more and lend less, which will drive up interest rates (r). When interest rates rise, desired investment falls. P r I (GDP demanded), so AD has a negative slope. 3) P NX: The Exchange-Rate Effect. When price levels rise, people need to hold more cash for transactions purposes, since prices are higher. To get more cash they will borrow more and lend less, which will drive up domestic interest rates (r). When domestic interest rates rise, everyone will seek to buy domestic bonds and sell foreign bonds, driving exchange rates up, and Net Capital Outflow (NCO) will fall. Since NCO=NX, and domestic currency appreciation discourages exports and encourages imports, NX falls too. P r NCO e NX (GDP demanded), so AD has a negative slope. In the U.S. economy, the interest rate effect is probably the most important of these three effects. In a smaller economy that relies more on trade, Belgium for example, the exchange-rate effect is stronger. What will shift the AD curve? Again, anything (other than a change in P) that affects C, I, G, or NX will shift the AD curve. Consequently, we have four categories of reasons for AD shifts: 1. AD Shifts Due to Consumption (C) Shifts. Examples include: If consumers decide to save less, C will rise and AD will shift rightward. If the government reduces taxes, C will rise and AD will shift rightward. If wealth increases due to a stock market rally or an increase in house prices, C will rise and AD will shift rightward. 2. AD Shifts Due to Investment (I) Shifts. Examples include: Improved technology makes investment more attractive; I will rise and so will AD. If business owners become more optimistic, I will rise and so will AD. If the government gives tax breaks for investment spending, I will rise and so will AD. The Fed increases the Money Supply to make interest rates fall, I will rise and so AD. 3. AD Shifts Due to Government Spending (G) Changes. Examples include Wars increase G and therefore AD. Capital projects (roads, canals, buildings, etc) increase G and therefore AD. 4. AD Shifts Due to Changes in Net Exports If foreign countries’ econonomies expand, foreigners will have more income to buy more of our exports, increasing NX and therefore AD will shift to the right. Changes in exchange rates due to central bank actions Remember, if the quantity of desired spending changes because of a change in the price level P, the AD curve does not shift. Instead, you move along a stationary AD curve. 6 Try This: What happens to the AD curve in each of the following scenarios? A. A ten-year-old investment tax credit expires. B. The U.S. exchange rate falls. C. A fall in prices increases the real value of everyone’s savings account. D. State governments replace their sales taxes with new taxes on interest, dividends, and capital gains. Answers: A: AD shifts left, because investment (I) falls. B: AD shifts right, because imports get more expensive and exports get cheaper, so NX increases. C: AD does not move; consumption increases, but it’s a movement to the right along a stationary AD curve because the increase in C is caused by a fall in P D: AD shifts to the right. C increases as savings falls, because there’s less tax on consumption, and more tax on the returns from savings. The Aggregate Supply Curve Aggregate Supply (AS) is the relationship between the aggregate price level P and the quantity that producers actually produce. The aggregate supply relationship is different in the long run than it is in the short run. The short-run AS curve has a positive slope, but the long-run Aggregate Supply (LRAS) curve is vertical. Why is the LRAS curve vertical? In the long run, the amount of production in the economy is determined by the physical ability to produce. The economy’s ability to produce depends on the full employment of its workers (L), their skills and education (human capital), social capital, physical capital (K), natural resources, and technology. None of these physical factors is affected by the aggregate price level, so the amount of output that the economy produces (at full employment) is the same, regardless of the price level. In other words, the Long Run Aggregate Supply (LRAS) Curve is Vertical, as illustrated in figure 6.5 below. 7 Figure 6.5: Long Run Aggregate Supply Notice that if the LRAS is vertical, a movement of the AD curve will change the equilibrium level of price, but not of real GDP, YFE. A vertical LRAS curve therefore indicates that the nominal variable (P) changes independently of the real variable (Y), so it is consistent with the Classical model, in which the classical dichotomy holds and money is neutral. Also, notice that the equilibrium level of real GDP in figure 6.5 is labeled YFE. The “FE” stands for “full employment.” YFE is the amount of real GDP that the economy will produce if all the inputs, including labor, are fully employed. Full employment does not mean that the unemployment rate is zero. Rather, it means that the economy is at the its Natural Rate of Unemployment. Recall from Module 2 that the Natural Rate of Unemployment consists of frictional plus structural unemployment, and it’s the rate of unemployment (about 5.5 to 6 percent in the U.S.) that the economy experiences when it is neither in recession, nor overheated. So, YFE is the amount of GDP produced when unemployment is at its Natural Rate. What Shifts the LRAS Curve? Since the position of the LRAS curve is completely determined by the level of Full Employment GDP (YFE), the LRAS curve will shift to the right whenever something happens that makes the economy more productive, and it will shift to the left whenever something happens that makes the economy less productive. Recall from Module 3 that the productive capacity of the economy, YFE, is determined by the availability of labor, capital, human capital, social capital, natural resources, and technology. Therefore, shifts of the LRAS curve will occur when one of these factors changes. Here is a list of possible shifters; in many cases it is indicated what changes will shift the LRAS curve outward (+), and which inward (-). 8 1) LRAS shifts when LABOR’s availability changes. This may occur when the number of workers changes due to immigration (+), emigration (-), plagues (-), or war (-). It may also occur when the natural rate of unemployment changes due to changes in minimum wage, unionization, unemployment insurance, or changes in the health care system. 2) LRAS shifts when the availability of PHYSICAL CAPITAL changes. This occurs when investment increases (+) or decreases (-) for a long period, or when some of the capital stock is destroyed by war or natural disaster (-). 3) LRAS shifts when the availability of HUMAN CAPITAL changes. This occurs when the educational system improves (+) or gets worse (-), or when the work force learns to use new tools such as computer hardware and software (+). 4) LRAS shifts when the availability of SOCIAL CAPITAL changes. This occurs when civil war starts (-) or ends (+), when corruption in government and the judicial system increases (-) or decreases (+), when the rule of law is established (+) or deteriorates (-), or in general when people in society get better or worse at getting along and working together. 5) LRAS shifts when the availability of NATURAL RESOURCES changes. This occurs when new sources of energy and other useful natural commodities such as iron ore or rare earths are discovered (+) or old sources are depleted (-); when prices of useful natural resources such as oil or natural gas rise (-) or fall (+) relative to other prices; when farmland is reclaimed (+) or depleted (-); or when clean air and water are polluted (-). 6) LRAS shifts when technology of production improves (+) or is forgotten (-). For example, during the 1990’s firms found new and productive uses for computers and the internet (+). Similarly, the use of hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling techniques have vastly increased the availability of natural gas and oil to the U.S. economy since 2006 (+). Figure 6.6 illustrates the effect of a rightward shift in the LRAS curve: the price level drops from P1 to P2, while the economy’s output increases. 9 Figure 6.6: Macroeconomic Effects of An Increase in Long Run Aggregate Supply Ever since the Industrial Revolution, developed countries have seen steady increases in LRAS because of steady technological improvements, high levels of investment, and increases in the size and quality of the workforce. Clearly, output has risen in the long run, as predicted by the AS/AD model in figure 6.6, but why haven’t prices fallen? Instead, for the past 80 years or so we’ve seen fairly steady increases in both output and prices, year after year. How can the AS/AD model explain this pervasive pattern of economic growth with moderate inflation? The answer is that the increase in population and in living standards, along with increases in the money supply, have driven the AD curve rightward too. These long run dynamics of the economy are illustrated in figure 6.7, which shows long-run economic growth with price inflation. If the AD curve shifts to the right more quickly than the LRAS curve, there will be inflation; if LRAS shifts faster, there will be deflation. 10 Figure 6.7: Long Run Growth with Inflation in the AS/AD Model The Short Run Aggregate Supply (AS) Curve The Aggregate Supply curve slopes upward in the short run. That is, if the aggregate price level increases, desired production will also increase, in the short run. When you consider that an increase in aggregate prices implies an increase in input prices (wages, rents, prices of materials and machinery) as well as output prices, it is unclear why an increase in aggregate prices would provide producers with an incentive to increase production. In other words, why does a purely nominal increase in prices affect real output? Why Does the Short-Run AS Curve Have a Positive Slope? There are several possible answers to this question, and economists disagree about the details of the answer. They generally agree, though, that any upward slope of the short run AS curve can be explained by misperceptions of prices, or poorly formed expectations about prices, which cause some prices to be “sticky.” That is, not all prices rise at the same rate. The “Sticky-Wage” theory provides one explanation of why the AS curve has a positive slope. The argument is as follows. For most goods, it is easy to raise or lower the price. Take gasoline, for instance. If the wholesale cost of gasoline goes up, Sheetz can raise its pump price very easily. If the wholesale cost of gasoline goes down the following week, Sheetz can easily lower the price at the pump. The price of labor, also known as the nominal wage rate W, is very different from the price of almost anything else. It is extraordinarily difficult to lower wages of current workers because lowering wages makes workers angry, and angry workers are less productive. Because it is so hard to lower nominal wages, employers are very reluctant to raise wages, even if the price of their product has risen. Nominal wages W are “sticky.” Suppose you run a pizzeria, and you notice that the other pizza places in town have quit offering special deals and discounts, so effectively the price of pizza gone up. You’re not sure if that is a 11 permanent price increase, or if it’s temporary. A higher pizza price would allow you to pay your workers more, but you’ll lose money if you raise their wages just before the price of pizza falls again. Holding your employees’ wages constant, when the price of pizzas rises your profits will increase, and that increased profit will make you try harder to produce more pizzas. In effect, the real wage that you are paying your workers (the price of an hour of labor divided by the price of a pizza) has fallen, even though the nominal wage W has stayed the same. You may even hire an extra worker or two at the current wage rate, since labor has become relatively cheap. Let’s suppose that the increase in pizza prices is in fact the result of a general inflation; that is, the price of pizzas is simply rising with the aggregate price level P. Because wages are sticky, when P rises, W/P falls, so your profits rise, and you produce more. Higher P, higher output: that means your supply curve slopes upward. If the same process is occurring throughout the economy, then aggregate output (real GDP) will rise when P rises. In symbols, we can summarize the sticky wage theory like this: P W/P Profits Y. One more detail of the theory is important: Current Nominal wages (W) are linked to expected prices at the time the wages are negotiated. When nominal wages are negotiated, both workers and employers take into account the level of prices that they expect. If the employer expects the price of the firm’s output to rise in the current year, it will be willing to pay a higher wage. If workers expect the prices of groceries and gasoline to rise in the current year, they will demand higher wages. Thus, nominal wages (W) rise and fall with the expected price level (EP). We can summarize this model of the short-run AS curve with the following equation: Y S = YFE + a(P EP) where a is a positive number related to the slope of the AS curve, Y S is real GDP produced in the economy, YFE is full-employment GDP, P is the current price level, and EP is the price level that was expected when wages were set. The AS curve described by this equation has these essential properties. The higher the current price level relative to expectations, the more real GDP supplied. If the price level is as expected (P EP) = 0, then the economy is at full employment (Y S = YFE + 0). If the current price level is higher than expected, then output exceeds full employment (Y S > YFE), and we’re in an unsustainable boom. If the current price level is lower than expected, then output is less than full employment (Y S < YFE), and we’re in a recession. Figure 6.8 is a picture of the relationship between AS and LRAS as described in our model of aggregate supply. Notice that the AS curve intersects the LRAS curve where P = EP. Notice also that if the aggregate price level is above EP (at P1, for example) real GDP supplied output on the AS curve (Y1) exceeds YFE. Similarly, if price is P2 < EP, then output is Y2 > YFE. 12 Figure 6.8: Relationship Between Long Run and Short Run AS. What will Shift the Short Run Aggregate Supply Curve? There are two things that will shift the short-run Aggregate Supply Curve: 1) Anything that shifts the LRAS curve also shifts the short-run AS curve. Anything that changes YFE, negative or positive, shifts both LRAS and AS. Figure 6.9, for example, shows what would happen to both AS and LRAS if there were a big increase in the price of oil, or if a disease or war killed a large percentage of the workforce, or if a natural disaster destroyed factories. Such an event is often referred to as a “negative supply shock.” Positive supply shocks are possible too, of course, for example when new supplies of natural gas are discovered, or immigration increases the size of the workforce. 13 Figure 6.9: A Negative Supply Shock Shifts both LRAS and AS 2) Changes in price expectations shift the short run AS but not LRAS. If sellers expect higher prices, EP will increase and the AS curve will shift to the left (upward), as shown in figure 6.10. Expectations of the price level don’t affect the economy’s productive capacity, though, so the LRAS curve does not shift when AS shifts due to a change in expected prices. Figure 6.10: An Increase in Price Expectations Shifts AS but not LRAS 14 AS/AD Model of the Business Cycle With an understanding of the AS/AD model, we can proceed to describe how the cycle of recession and recovery occurs within that model. Our analysis will ask four questions about the effects of an event on the macro economy: 1) Which curve will shift? (AS or AD) 2) Which way will it shift? (left, or right) 3) What happens to short-run equilibrium P, Y, and Unemployemnt U? ( or ) 4) How does the economy adjust in the long run? (Does it move back to YFE?) The first three questions are just like the questions we always ask when manipulating supply and demand models. The only change is that we also ask about unemployment effects; remember, U always goes in the opposite direction as Y: The more GDP, the less unemployment. Question 4 is unique to AS/AD models, and it expresses the ability of the economy to recover on its own in the long run. Long Run Equilibrium Figure 6.11 shows the macroeconomy in long-run equilibrium, which is where LRAS, AS, and AD cross. Notice that in long-run equilibrium the price level P0 is equal to EP, which is the price level that people expected. Also, Real GDP is at its full employment level, YFE. Figure 6.11: Long Run Equilibrium of Aggregate Supply and Aggregate Demand How does the economy reach equilibrium? If the price is higher than P0, then domestic firms produce more output than consumers, investors, government, and foreigners want to buy. Inventories pile up, and prices fall toward equilibrium. If the actual price is lower than P0 then 15 desired spending will exceed production, inventories will fall, and prices will rise toward equilibrium and the economy will move toward full employment YFE. A recession begins when something bad happens to the economy that shifts either AS or AD to the left. These events are sometimes called negative “shocks.” Many economists believe that demand shocks are more common. Both the Great Depression of 1929-1932 and the Great Recession of 2007-09 started with financial panics during which Investment spending fell, and the effects of both shocks lingered for many years after. 1) Demand-Driven Recession Any of the AD curve shifters could set off a recession, but usually AD-driven recessions begin with a drop in investment. The economy started out in long run equilibrium at point A, with price level P1 and full employment output YFE. Then, as in 2008, financial panic strikes, firms become pessimistic about future sales, and so their Investment spending for new facilities dries up. Figure 6.12: A Negative Aggregate Demand Shock Causes Recession Which curve shifts? (AD, since AD = C + I + G + NX and I was affected by the panic.) Which way does it shift? (To the left: AD from AD1 to AD2, since I fell). What happens to P, Y, and U? (Since short-run equilibrium moves from point A to point B, P falls from P1 to P2. Output falls from YFE to Y2, so Unemployment increases above the Natural Rate of Unemployment. P, Y, U.) Since output is below YFE and unemployment is above its natural rate, we have a recession. Long Run Adjustment and Recovery to Full Employment In the long run, most economists believe that the economy will recover and return to full employment on its own. How does this happen? Workers experience high unemployment and 16 lower prices, so they lower price expectations and are willing to accept lower nominal wages. Nominal wages can not fall until expected future prices EP fall. People form price expectations based on their experience, so it will take some time (the “long run”) for expected prices to fall. Figure 6.13: The Economy Recovers from Recession Profitability of firms improves as nominal wages fall, so the short-run AS curve shifts to the right, as shown in green in figure 6.13. Output increases and unemployment falls when the AS curve shifts. Prices continue to fall, price expectations (EP) continue to adjust downward and the AS curve continues to shift to the right, until the economy returns to full employment at point C in figure 6.13. Point C is a new point of long run equilibrium, where prices equal expected prices. In symbols, we say in the long run: P EP W W/P Profits AS Y, U Expressing the same long-run adjustment in terms of our three supply-and-demand questions: When, in the long run, price expectations (EP) fall: Which curve shifts? AS, since a drop in EP allows W to fall. Which way? To the right. AS, so the equilibrium point moves from B to C. What happens to aggregate price, real GDP, and unemployment? P, Y, U. 17 Summary of the AS/AD Model of a Demand-Driven Recession and Recovery: Short Run (A to B in fig 6.12): Demand Shock (usually Investment) AD P, Y, U. Long Run (B to C in fig 6.13): P EP AS P, Y, U In the Short Run, a decrease in the price level due to a shift in AD reduces output (because short run AS slopes upward) In the Long Run, a decrease in AD will affect only the price level, not output (because longrun AS is vertical). Once real GDP returns to YFE, P = EP = P3, and the recovery process stops. In a sense, the entire course has been leading up to this description of the business cycle, it’s VERY IMPORTANT that you fully understand it. Take a little while to study it, and sketch out your own versions of figures 6.12 and 6.13 on paper without looking. Master this, and convince yourself that you understand the reasons for each curve shift (long run and short run) before you move on. Once you’ve mastered the model of recession and recovery, TEST YOURSELF by answering this question: Suppose that the economy has recovered and returned to point C. At this point, business people get so excited about the recovery that they become overly optimistic and start on an investment spending binge, building new factories and housing and buying new machinery that are unlikely to pay for themselves in the long run. Using the AS/AD model, show the effects of this investment binge on aggregate price P, real GDP (Y), and unemployment U, in the short run and the long run. Explain the role of price expectations in the process. Answer: (See figure 6.14) Short Run: I AD (P, Y, U). The economy moves to point D in figure 6.14. Inflation occurs, unemployment falls below its natural rate, and GDP moves to Y1, which exceeds YFE. This increase in Y can only occur because expected prices (and therefore nominal wages) remain constant, so the AS curve stays at AS2. Long Run: P EP AS P, Y, U. As prices rise, so do price expectations and nominal wages, and the AS curve shifts to the left. Price will continue to rise, and output Y will continue to fall, until the economy reaches Long Run Equilibrium at point A, where P = EP = P5, unemployment is at its natural rate, and Y = YFE. 18 Figure 6.14: Bubbly Boom and Bust In the AS/AD model, the business “cycle” consists of the movement around the circle from full employment (point A) to recession (point B) through recovery to full employment (C), often followed by a boom (D), and a correction back to full employment (A). YFE changes over time as the population grows and technology improves, but the business cycle causes output, unemployment, and prices to fluctuate around YFE. In an AD-driven recession both the price level and GDP decline together as the recession hits, moving the economy from point A to point B. Specifically, in the Great Depression real GDP fell by about 33% during four years following the financial panic of 1929, and the price level fell by about 22%, while the unemployment rate rose from 3% to about 25%. In most AD-driven recessions since that time prices have not actually fallen, and real GDP often has not fallen. Still, the rate of inflation and the rate of GDP growth have both slowed during all AD-driven recessions. 2) Aggregate-Supply-Driven Recessions In an Aggregate-Supply-driven recession, in contrast, inflation rises as real GDP growth falls, which makes a combination of inflation and economic stagnation called “stagflation.” Stagflation in the AS/AD model is shown in figure 6.15. An Aggregate Supply shock initiates an episode of stagflation. This may be a big increase in the price of crude oil, as occurred in 1973 during the Yom Kippur War and again in 1979 as a result of the Iranian Revolution. Other possibilities include a decline in population or destruction of factories and farms due to war or disease or natural disaster, such as occurred in the Confederacy in 1864-65, or in late Medieval Europe during the Black Plague. 19 Figure 6.15: Aggregate Supply Shock and Stagflation Whatever the nature of the supply shock, it will reduce the productive capacity of the economy, driving both long-run and short-run aggregate supply to the left (from LRAS1 to LRAS2 and from AS1 to AS2), as shown in figure 6.15. In the short run, prices rise (from P1 to P2), and output falls (from Y1 to Y2) as the economy moves from point A to point B. Full-employment output falls even farther, from Y1 to Y3. In the long run, there will be further inflation and further reductions in output, as price expectations increase, driving the short run AS curve to AS3, and bringing the economy back to long-run equilibrium at point C. Clearly, an aggregate supply shock is a very bad thing for an economy, as President Jimmy Carter learned when he ran for re-election in 1980 with CPI inflation at about 13% and unemployment at nearly 8%. 20 Figure 6.16: Real GDP Growth (blue) and Inflation (GDP Deflator, green) The gray bars in figure 6.16 indicate the seven recesssions of the U.S. economy since 1965. The blue line shows real GDP growth, while the green line shows inflation as measured with the GDP deflator. In the graph you can identify demand-shock recessions as those in which inflation and GDP growth both declined (1982-83, 2001, 2007-2009, and, less obviously 1969-70 and 1990-91). You can identify the supply-shock regressions (stagflations) as those in which inflation rose and real GDP declined (the oil-price shock recessions of 1973-75 and 1980). Monetary Policy, Fiscal Policy, and Aggregate Demand (Mankiw Chapter 16) Recessions cause high unemployment with its attendant suffering and loss of production. This course concludes with a review of how and why most economists believe that certain government and central bank policies could, in theory at least, reduce the length and severity of recessions. We will also sketch out the arguments as to whether or not government policy can in fact effectively reduce the severity of the business cycle, and whether or not it should attempt to do so. Two types of policies: Monetary and Fiscal. When the Federal Reserve increases or decreases the rate of growth of the money supply M it is conducting MONETARY POLICY. When Congress increases or decreases government spending G or taxes T it is conducting FISCAL POLICY. Both types of policies affect the business cycle by shifting the Aggregate Demand curve. Recall that Aggregate Demand is the relationship between the aggregate price level P and desired spending Y = C + I + G + NX. Monetary policy affects interest rates, which affect I. Fiscal policy affects G directly, and it affects C indirectly by changing disposable income. 21 Monetary Policy Monetary policy affects AD by influencing interest rates: M r I AD. How does the money supply affect interest rates? The Theory of Liquidity Preference, by John Maynard Keynes, provides an explanation. The Theory of Liquidity Preference is really just a supply-and-demand analysis of money, but with the interest rate r, rather than the value of money, on the vertical axis, as shown in figure 6.20: Figure 6.20: Theory of Liquidity Preference The money supply curve is vertical at MA, reflecting the assumption that the money supply is set by the Federal Reserve. Keynes’s Theory of Liquidity Preference is expressed in the money demand curve. Why does MD have a negative slope? Think of money as an asset that you can own, a place you can store your wealth as an alternative to interest-bearing assets such as bonds. If you have $100,000, you can hold part of it, all of it, or none of it in the form of money. Suppose you decide to hold all $100,000 in cash. You’re giving up the interest on $100,000. On the other hand, if you used the cash to buy $100,000 in bonds, you might have trouble selling those bonds if you wanted to buy something, or if you needed the cash quickly for an emergency. Also, if the riskiness of your bonds increases, the value of your bonds will decrease. So, there’s great convenience (and some safety) in holding your wealth in liquid (money) form, but you sacrifice interest payments when you do so. The higher the interest rate r, the greater your sacrifice, and the less money and more bonds you are likely to hold. In figure 6.20, suppose the current interest rate is rB, so the quantity of money demanded is MB, but the money supply is at MA. There is more money in the economy than people want to hold, so they go looking for ways to lend it out (and obtain bonds). There are not enough people 22 willing to borrow at rate rB, and some of the people holding cash will be willing to lend at a lower interest rate, so market interest rates will fall until interest rates reach equilibrium at rA. Money Demand increases (the MD curve shifts to the right), when people choose to hold more cash regardless of the interest rate. This frequently occurs when people lose faith in the value of bonds during financial panics. It also can occur in wartime, or in other times of uncertainty when people value the flexibility of money balances. For example, there was a brief but substantial surge in the demand for money following the events of September 11, 2001. By the same token, Money Demand will shift to the left when people become more confident about the future, and also when technological changes such increased credit card usage reduce the need to carry cash. Note that when MD shifts to the right, interest rates increase, and when MD shifts to the left interest rates decrease. (Try drawing the liquidity preference diagram 6.20 on paper from memory, shift MD to the right and see what happens.) When MD increases during a financial panic, the Fed typically will increase the money supply to satisfy the increased demand without an increase in interest rates. Figure 6.21: Effect of Monetary Policy on Interest Rates Now, suppose the Fed decides to increase the money supply from MA to MC, as in figure 6.21. Again, when the interest rate is at rA there’s a money surplus, and people seeking to get rid of their cash and buy bonds will drive interest rates down to rC. By shifting the money supply curve to the left, it’s easy to see that the Fed can raise interest rates by reducing the money supply. As an exercise, try drawing the liquidity preference diagram like figure 6.20 from memory, shift MS to the left, and show the effect of a reduction of the money supply on interest rates. 23 Interest Rates Affect Investment Spending (I) Investment spending (I) usually involves borrowing. Businesses borrow in order to build new stores, restaurants, and factories, and to buy new machinery for their workers to operate. Individuals take out mortgages in order to invest in new housing. The cost of borrowing money is the interest rate. When interest rates rise, investment spending falls, and when interest rates fall investment spending rises. Investment spending is part of Aggregate Demand (AD): Y = C + I + G + NX. Falling interest rates cause investment spending (I) to rise, which increases Aggregate Demand. Expansionary Monetary Policy: An expansion of the money supply by the Fed causes interest rates to fall, which stimulates investment spending, which causes the AD curve to shift to the right, and causes higher prices and higher real GDP in the short run, as shown in figure 6.22. To summarize in symbols, M r I AD (P, Y, Unemployment.) Figure 6.22: Effect of Expansionary Policy on AD/AS As we have seen in a previous module, the Fed most commonly implements expansionary monetary policy (expands the money supply) when the FOMC buys bonds. Other examples of expansionary monetary policy occur when the Fed lowers interest on reserves (IOR), lowers the required reserve ratio, or offers to lend reserves to banks at a lower interest rate. The Fed implemented several additional, rather creative, expansionary policies during the financial panic of 2008-2009. Contractionary Monetary Policy: A contraction of the money supply by the Fed causes interest rates to rise, which reduces investment spending, which causes the AD curve to shift to the left, and causes lower prices and lower real GDP in the short run. To summarize in symbols, M r I AD (P, Y, Unemployment.). 24 The Fed most commonly implements contractionary monetary policy (contracts the money supply) when the FOMC to sells bonds. Other examples of expansionary monetary policy occur when the Fed raises interest on reserves (IOR), raises the required reserve ratio, or deters banks from borrowing reserves by raising its interest rate. The most dramatic and effective application of contractionary monetary policy occurred during 1980-83, when Fed Chairman Paul Volcker (with support from Presidents Carter and Reagan) caused a severe recession, driving unemployment up to nearly 11% in 1982. The contractionary monetary policy also put an end to the double-digit inflation rates of the 1970s. The recession soon ended, but the decline in the inflation rate was permanent. It fell from nearly 15% in mid-1980 to less than 4% by the end of 1982, and it stayed low. Inflation averaged less than 3% for the following 30 years. Fiscal Policy: Changes in G and Taxes (T) Fiscal policy affects Aggregate Demand directly, by changing government spending G: G AD (since AD is C + I + G + NX), and indirectly by changing consumers’ disposable income through taxation (T): T Disposable Income C AD. Disposable Income is simply the income that people have left over after they pay their taxes, DI = (Y – T). Government spending (G) and taxation (T) in the United States are determined by Congress, under the leadership (and potential veto) of the President. Expansionary Fiscal Policy: An increase in government spending (G) or a tax cut (T) are both considered expansionary. Again, the increase in G affects AD directly: G (C+I+G) AD (P, Y, Unemployment.) while the tax cut affects AD because lower taxes leave consumers more disposable income: T DI C (C+I+G) AD (P, Y, Unemployment). World War II involved a massive increase in government spending, an expansionary policy that is widely (though not universally) credited with bringing the United States out of the Great Depression. (Hitler’s military buildup provided a similar stimulus to the German economy in the 1930s.) Notice that expansionary policy, by increasing government spending G and decreasing government income T, increases the government’s budget deficit (G – T), forcing the government to borrow and reducing national saving. If the government was running a fiscal surplus (T – G > 0) prior to implementing expansionary policy, expansionary policy reduces the surplus and national saving. Contractionary Fiscal Policy: A decrease in government spending (G) or a tax increase (T) are both considered contractionary. G (C+I+G) AD (P, Y, Unemployment.) while the tax increase affects AD by leaving consumers with less disposable income: T DI C (C+I+G) AD (P, Y, Unemployment). Because of large government budget deficits in 2008-2011 many countries in the world, including the United States, implemented “austerity” measures designed to reduce those deficits, primarily by reducing government spending. Though these austerity measures have found considerable support among economists worried about the negative effects of government debt on economic growth, many others argue that these spending cuts were contractionary and therefore prolonged the Great Recession. 25 Figure 6.22 above shows the effect of expansionary fiscal policy on the AS/AD model of the economy. It looks identical to the effect of expansionary monetary policy, though it arises from a very different source. The Fiscal Multiplier Effect There is considerable controversy among economists as to exactly how much an additional dollar of government spending or tax cuts will increase AD. Let’s consider tax cuts first. Suppose Congress enacts a tax cut of $1000 per person. The average person getting an additional $1000 in income will spend some of it (C) and will save some of it. Overall spending (AD) will increase only to the extent that the person spends that tax cut on additional consumption spending. Suppose that the average person spends $900 of his or her $1000 tax cut. In that case, the AD curve will initially shift to the right by $900. (The actual increase in short-run GDP will be somewhat less than $900, since the AS curve slopes upward, as shown in figure 6.22.) John Maynard Keynes, shown in the photo to the right, based much of his theory on this human tendency to increase spending by less than a dollar when income rises by a dollar. He stated it thus: "The fundamental psychological law upon which we are entitled to depend with great confidence, both a priori from our knowledge of human nature and from the detailed facts of experience, is that men are disposed, as a rule and on average, to increase their consumption as their income increases, but not by as much as the increase in their income." J.M. Keynes, General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money, 1936 He gave a name to this concept: the Marginal Propensity to Consume. Definition: The amount of additional consumption spending induced by an additional dollar of disposable income is called the Marginal Propensity to Consume, or MPC. The MPC can be calculated as follows: MPC = Change in Consumption Change in Income In the $1000 tax cut example described above, MPC = (900/1000) = 0.9. Another way of thinking of it is that a tax cut in the amount T will induce an immediate increase in consumption spending, and therefore an immediate rightward shift of the AD curve, equal to MPC x T, so a $1000 tax cut will increase Aggregate Demand by MPC x $1000 = $900 almost immediately. The effects of the tax cut can expand and multiply. The $900 of additional consumption spending (say, on a new TV) will be an additional $900 in income to the people who produce and sell the TV. Of that additional $900 income, those TV sellers will consume an additional MPC x $900 = $810, which will be income to someone else, who will spend MPCx$810 = $729, and so on and so on. This is called the “Keynesian Multiplier” process. Here’s what you need to know about the Keynesian Multiplier: 1) It is a model of how an additional dollar of G or decrease in T affects the AD curve, and 2) The multiplier is larger when MPC is larger. You should also see that a $1 billion increase in G has a larger multiplier effect on AD than a $1 billion tax cut T, since the full $1 billion of G is spent on goods and services, whereas only MPC xT is spent in the initial round of spending from a tax cut. Finally, notice that the multiplier process works in reverse, too. If G falls by a dollar (or T rises by a dollar) AD may decrease (shift to the left) by much more than a dollar, since a decrease in 26 spending results in a decrease in income, which causes consumption spending to decrease, which decreases income further, and so on. Limitations on the Multiplier Effect of Expansionary Fiscal Policy There are at least two major reasons to believe that the multiplier effect is limited, and hence to doubt the ability of expansionary fiscal policy to fix a recession. In both cases, the expansionary policy has a side effect that causes some category of spending (I or C) to decrease. 1. Crowding Out: Expansionary fiscal policy consists of increases in G and decreases in T, either one of which will increase the government’s budget deficit, G – T. When the budget deficit increases, national saving decreases, which our Loanable Funds model tells us will drive up interest rates and decrease investment spending, shifting AD back to the left. To summarize “Crowding Out”: Expansionary policy (G, T ) S r I AD. 2. “Ricardian Equivalence.” Other things constant, when the government increases spending and cuts taxes it creates debt that must be repaid someday, which will require higher taxes in the future. People will reduce their consumption spending (C) today so as to have money available later on to pay those higher taxes. To summarize “Ricardian Equivalence”: Expansionary policy (G, T ) Expected future taxes) S C AD. Most economists believe that the crowding out effect is greater when the economy is at full employment, so the multiplier is higher when the economy is in recession. (Crowding out does not occur without an increase in interest rates.) As to Ricardian Equivalence, some economists dismiss it almost entirely, since (1) people may not really plan that far ahead; (2) even forwardplanning people may believe that higher future taxes will be paid by someone else; and (3) not everyone is able to save even if they want to, particularly during a recession. To summarize, the exact size of the Keynesian multiplier is controversial among economists, most believe that higher government spending and lower taxes stimulate aggregate demand to some degree in the short run, that the multiplier is higher during recessions than during times of full employment, and that the multiplier is higher if MPC is higher. Using Policy to Stabilize the Economy In this final section of the course we’ll first consider the ideal model of how fiscal and monetary policy could be used to counteract the business cycle, and describe why most economists believe that government policy could in principle stabilize the business cycle to avoid depressions and reduce the great pain and waste created by boom and recession. We’ll go on to explain why, in normal times at least, most economists are skeptical that active fiscal policy is useful for stabilizing moderate fluctuations of the economy. We’ll see why many economists are more inclined to rely on monetary policy for stabilization in normal times, and why many others recommend against active policy of either type. The Case FOR Active Stabilization Policy The extremes of the business cycle are costly. High unemployment during recessions causes great pain to millions of idled workers, causes their skills to deteriorate, and results in a loss of production to society that can never be recovered. During extreme booms, excessive speculation, bubbles, and poor investment decisions waste resources and set the stage for failure. Stabilization policy can reduce the costs of boom and bust. 27 Figure 6.23: Expansionary Policy to Reduce Unemployment and End a Recession Figure 6.23 illustrates how expansionary fiscal or monetary policy can be used to end a recession. Suppose the economy is in recession at point A. Production is at Y1, well below full employment YFE, which means that the unemployment is above the natural rate. Classical economists would say not to worry, in the long run price expectations and wages will adjust downward, which will shift short run AS curve will shift to the right, which will end the recession at point C in the long run. In some recessions, including the Great Recession of 2007-09, though, the long run is very long indeed. Five years after the financial panic that brought on the recession, the unemployment rate was still near 7%. As Keynes said, “in the long run we’re all dead.” FDR’s advisor Harry Hopkins put it this way: “People don’t eat in the long run. They eat every day.” Waiting for the long run adjustment is costly and painful. If the long-run shift of the AS curve to point C is slow for some reason, expansionary monetary or fiscal policy can intervene to move things along and put people back to work. A massive bond purchase by the Federal Reserve, or a Congressional bill to increase in government spending or give a tax cut, will shift the AD curve to the right. If the expansionary policy is measured correctly it will shift the economy from point A to point C by moving the AD curve from AD0 to AD1. At the cost of some inflation (price rises from P0 to P1), expansionary policy will drive real GDP upward from Y0 to Y1 and unemployment will fall to its natural rate. 28 That’s how expansionary fiscal policy works in an ideal world. Increased government spending brings the economy back to full employment by replacing the decreased private spending that drove it into recession. Tax cuts ameliorate the effect of depressed private spending by stimulating consumption. Expansionary monetary policy offsets depressed AD by driving interest rates down to stimulate investment. Whether it’s fiscal or monetary, expansionary policy is designed to reduce or eliminate the impact of a recession. Contractionary monetary and fiscal policy has exactly the opposite effect, and it is designed to cool the economy off, to reduce or eliminate an excessive boom. (As longtime Fed Chair William McChesney Martin put it, the Fed “is in the position of the chaperone who has ordered the punch bowl removed just when the party was really warming up.”) If real GDP is greater than full employment GDP, the correct fiscal stabilization policy would be contractionary, to reduce government spending or raise taxes. If real GDP is greater than full employment GDP, the correct monetary policy would be contractionary, to sell bonds so as to reduce the money supply. In either case, contractionary policy reduces real GDP, which is a good thing if the economy is overheated. Test Your Understanding: Draw a diagram with the AS, AD, and LRAS curves showing the economy in a boom with output above full employment. (Be sure to label all curves, axes, YFE, and short-run equilibrium P and Y, and draw your AD and AS curves so that initial short-run equilibrium output exceeds YFE.) Now show the effect of contractionary policy in bringing the policy back to full employment. Contrast that policy effect with the economy’s natural movement to full employment, which will occur as price expectations adjust upward to reality. Does the policy adjustment or the natural adjustment of the economy generate higher inflation? Stabilization Policy and the Budget Deficit. Often Keynesian economists who advocate active fiscal policy are accused of fiscal irresponsibility because expansionary fiscal policy (increasing G, decreasing T) causes budget deficits (T – G > 0). Certainly, Keynesian economists do recommend increasing the budget deficit during recessions, because increased deficits are expansionary. On the other hand, they recommend that the government run a budget surplus during excessive booms, since increased budget surpluses (G – T > 0) are contractionary. Keynesian economists therefore recommend fiscal policies that balance the budget over the business cycle, rather than balancing it every year. Although Keynesian economists usually advocate active government stabilization policy to counteract the business cycle, and Keynesian economists tend to be less skeptical of government’s role in the economy than economists from many other schools of thought, Keynesian theory is neutral with respect to the size of the government, and Keynesian stabilization policy strictly applied would not increase government debt in the long run. The Case AGAINST Active Stabilization Policy The business cycle creates great pain and waste because it causes wasteful investment spending and bubbles during booms and wasteful unemployment during recessions. If active stabilization policy can reduce this pain and waste, why would anyone argue against it? There are several strong arguments against active stabilization policy. The arguments against active monetary policy are somewhat different (and weaker) than the arguments against active fiscal policy. 29 Arguments Against Active Fiscal Policy: (1) Congress makes the decisions as to spending and taxation, and Congressmen are poorly equipped to perform fiscal policy. First, Congressional leaders are rarely well trained in either diagnosing the problems of the economy, and they even more rarely understand how to formulate and implement the correct cures for the country’s economic problems. Furthermore, Congressional decisions on spending and taxation are driven by many factors other than economic stabilization. Congressmen want to be re-elected, and the easiest way to get re-elected is to spend more on your constituents, and tax them less. Some would even argue that the political system is biased toward implementing the wrong policy. Income falls during recessions, and people become pessimistic about the future. Active policy calls for increased government spending during recessions, but recessions cause ordinary people to cut their spending, which makes them want to see government cut its spending too. Such “austerity” arguments dominated the policy debates in the beginning of the Great Depression (1929-32), again in 1937, and yet again in 2010-2014, making it politically difficult to implement expansionary fiscal policy. Similarly, there is a tendency to increase spending and cut taxes during optimistic boom times, for example during the late 1960s and 2001-06, making it politically difficult to implement the appropriate contractionary policy. (2) Even if Congress does implement the appropriate fiscal policy, it will often do so too late. Congress takes a long time to act in normal times. By the time it passes a law, the economy may have encountered new and different problems, or it may have naturally recovered from the recession. (3) Even if Congress does implement the correct fiscal policy promptly, it is difficult to say how long it will take for the policy to take effect. Individuals may not spend their tax cuts until they are certain they are permanent. It may take years for a new highway project or a new building project to progress from authorization through the planning stages to the point where the money is being spent. Arguments Against Active Monetary Policy (1) Unlike fiscal policy, which is driven by distracted Congressional policy amateurs, monetary policy is driven by Federal Reserve policy experts whose minds are always concentrated on monetary policy. Still, even those experts at the Fed are driving the economy with a limited set of information. In particular, they don’t know much about the future. It’s as if the Fed is trying to drive a car with so much mud on its windshield that the driver must steer by looking in the rearview mirror. It’s very easy for even an expert driver to do more harm than good in these circumstances. A driver who can’t see ahead is well-advised to drive slowly, cautiously, and predictably. (2) Like fiscal policy, monetary policy takes effect only with a lag, and the length of the lag is variable and uncertain. Remember, an increase in the money supply drives interest rates down only if people decide to lend out their excess money balances. (3) Under some circumstances (a “liquidity trap”), monetary policy is unable to stimulate the economy. Sometimes (as in 2009-13) people and businesses decide to hold on to their money rather than lend it. Also, expansionary monetary policy works by lowering short-term nominal interest rates, and when nominal interest rates are very close to zero (as in 200913) they simply can not go any lower. There’s another argument against fiscal policy that has intuitive appeal, but is most likely false when the economy is in a deep recession. Sometimes you will hear the argument that “if the government increases its spending, those dollars have to come from somewhere, and that means that a dollar more of government spending implies a dollar less of private spending.” The 30 problem with this line of argument is that it “proves too much.” That is, if it is true that increasd government spending can not stimulate the economy, then it’s also true that increased private spending can not stimulate the economy either, and for the same reason. For example, if all the homebuilders in the country decide to spend an additional billion dollars on housing, “they have to get those dollars from somewhere,” so the non-homebuilding part of the economy will have to shrink by one billion dollars. If increased government spending can’t stimulate the economy, then neither can increased private spending. An increase in spending (public or private) can increase real GDP if it puts idle resources (such as unemployed workers or idle machinery) to work. Employing more resources increases output. Increased spending can therefore have a bigger stimulative effect if there are more unused resources available, which is the case during recessions. How big this effect is in the real world is a matter of active debate in the economics profession. Some economists who oppose active stabilization policy argue that increased government spending during a recession is a bad idea because government is too big, so increased government spending is always a bad idea. This is a reasonable political position to take, and it probably underlies much of the opposition to activist stabilization policy, but it is really an argument about values, not about efficacy. Often the same economists that are suspicious of activist government in general also argue that Keynesian stabilization policy can too easily be used to justify especially wasteful government spending. Keynesian theory does in fact suggest that even wasteful spending is expansionary, but all economists agree that it is better to spend the money on needed infrastructure, such as roads and airports and schools than on bridges to nowhere and monuments to politicians. Finally, some economists argue that fiscal stabilization policy is a bad idea because recessions perform a purging and cleansing function that makes the economy stronger in the long run. It is true that recessions cause many poorly run businesses to fail, but they also cause many wellrun businesses to fail, and they idle many productive resources, including workers thrown into unemployment. Accurately comparing the real costs of recessions to the possible benefits from “macroeconomic purging” in recessions is impossible to do, and some skepticism is surely justified when tenured economics professors claim that other people’s unemployment is a cost worth bearing! Automatic Fiscal Stabilizers Some fiscal stabilization policies are already “built in” to the tax and spending system. These policies are called “automatic stabilizers,” and they act like a thermostat to lessen the costs of the business cycle. Two examples are progressive income taxes and unemployment insurance. In a progressive income tax system such as the one in the United States, people with higher incomes pay a higher percentage of their income in taxes. By the same token, people with lower incomes pay less of their incomes in taxes. Incomes decline during recessions, so recessions automatically cause taxes to decline as a percentage of national income. Tax cuts are expansionary, and expansionary policy is appropriate during a recession, so if there is a progressive income tax system then recessions trigger appropriate expansionary policy automatically, without Congress or the President having to act. Similarly, the income tax system automatically implements a contractionary tax increase during a boom. Similarly, the government pays unemployment insurance only to workers who have been laid off of work. Therefore, the layoffs that occur during a recession automatically cause an expansionary increase in government spending. (A contractionary decrease in unemployment insurance occurs automatically during boom times. Other programs to aid the poor have similar stabilizing effects on the economy. 31 Notice that automatic stabilizers do not have the problems with lags or doubtful management that other fiscal stabilization policies do, because they are implemented promptly and automatically. The Great Recession and Policy Debate Economists disagree vehemently on nearly everything concerned with stabilization policy. There is broad agreement, however, that in normal times fiscal stabilization policy (other than automatic stabilizers) is too uncertain and unstable and slow to be useful. Most economists agree that if you are going to implement stabilization policy, in normal times it’s better to rely on monetary policy than fiscal policy. The onset of the Great Recession in 2008, and the subsequent slow recovery created an ideal atmosphere for a loud and often acrimonious debate among economists and politicians about stabilization policy. In the United States, in the spring of 2009 a Democratic-controlled Congress and White House implemented expansionary fiscal policy by passing a stimulus bill, the American Reinvestment and Recovery Act (ARRA) that included about $500 Billion in increased spending and $300 Billion in tax cuts, spread over the next two years (mostly). Meanwhile, the Fed pumped reserves into the banking system in the years following the financial panic of 2008, causing the monetary base to expand at a rate of 28% per year 20082013. The money supply (M2) grew by a more modest 7% per year. Despite this increase in the money supply, core inflation remained between 1% and 2% for nearly all of this period. GDP fell nearly 3% in 2009, so automatic stabilizers kicked in even more quickly than the ARRA did, and the federal government’s budget deficit consequently ballooned to almost 10% of GDP by 2009. Unemployment maxed out at about 10% in October 2009, the highest in 26 years, but well below the Great Depression level of 25%. The debate over the effectiveness of ARRA and Fed policy has been bitter and partisan, even among professional economists. By 2011 Republicans had taken over the House of Representatives. Government spending and the deficit began declining (and tax collections began increasing) as a percentage of GDP as the economy began its natural recovery and fiscal policy shifted toward austerity and deficit reduction. Democrats and many Keynesian economists partly blame the slow recovery on contractionary fiscal policies, though they also note that recoveries from financial panics are typically slow in any case. Republicans and many conservative economists doubt the effectiveness of the ARRA and believe that business uncertainty created by dramatic fiscal and monetary (and regulatory) policies played a role in slowing the recovery from the recession. A more mainstream view is that the ARRA and the Fed’s policies had measurable expansionary effects. Whether because they were ineffective or because they were too small, it is clear that expansionary fiscal and monetary policies were unable to fully counteract the depressing effects of the largest financial panic in 80 years.