seeing the visual in argumentation

advertisement

ARGUMENTATION AND ADVOCACY

43 {Winter & Spring 2007): 144-151

SEEING THE VISUAL IN ARGUMENTATION:

A RHETORICAL ANALYSIS OF UNICEF

BELGIUM'S SMURF PUBLIC SERVICE

ANNOUNCEMENT

Katherine L. Hatfield, Ashley Hinck, and Marty J. Birkholt

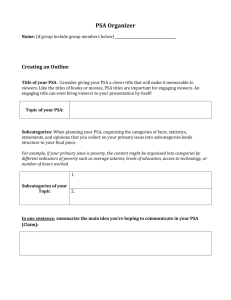

This paper applies J. Anthony Blair's theorizing about visual argumentation to the 2005 United Nations

Children's Fund (UNICEF) Smurf public service announcement, which challenges our traditional understanding of argumentation as linguistically bound. This paper critically analyzes the PSA and offers several

implications for scholars of argumentation and rhetoric. The project urges further expansion of Blair's

perspective in hope that we can viove beyond acknowledging the existence of visual arguments to identifying their

utility and functions.

K e y words: visual argument, UNICEF, Smuifs, cartoons

I

I

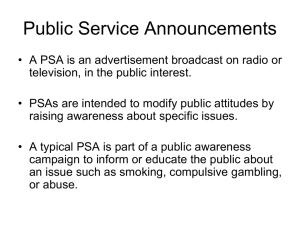

In the fall of 2005, the United Nations Children's Fund, better known as UNICEF, took

a different approach to pleading for donations. They created a public service announcement

(PSA) illustrating the horrors of war by using . . . Smurfs. This PSA was used in an effort to

raise $150,000 to assist former child soldiers in Burundi, Congo, and Sudan ("FAQ," 2005;

Rennie, 2005).

Philippe Henon, press officer for Belgium UNICEF, explains that "traditional images of

suffering in Third World war zones had lost their power to move television viewers" (Rennie,

2005, ^ 3):

The public's resistance to the more traditional advertising campaigns can be explained by the fact that people

have gotten "used" to seeing traditional images of children in despair in (mostly) African countries. Those

images are broadcasted or published almost daily and people are no longer "surprised" by seeing them and

most certainly don't see them as a call for action. (P. Henon, personal communication.January 6, 20()f))

Essentially, viewers experience fatigue. After being exposed to the images so often, they

become disinterested and no longer engage actively with them. UNICEF chose to stray from

its typical modus operandi which captures childhood innocence by presenting real life images

of carefree children (Spongenberg, 2005). But UNICEF felt that a more aggressive approach

was necessary. In an attempt to shock viewers into action, it deployed our childhood cartoon

friends: the Smurfs.

The 30-second spot aired from the fall of 2005 until April 2006. Although the cartoon's

typical audience consists almost entirely of young children, Belgian television networks ran

the spot only after 9:00 p.m. so as to minimize viewership by younger audiences. International agencies like UNICEF seldom choose cartoon characters to convey their message.

Instead, they emphasize the realism of htiman suffering. This drastic departure invites us to

ask what UNICEF's Smurf PSA can teach us about reaching desensitized audiences.

Because this is a public service announcement, it is appropriate to draw our critical

perspective from concepts relevant to the study of visual argument. J. Anthony Blair's (1996)

Katherine L. Hatfield, Ashley Hinck, and Marty Birkholt, Department of Communication Studies, Creighton University. An

earlier version was presented at the annual meeting of the National Communication Association, .San Antonio, TX,

November, 'iOOti. The authors would like to thank Philippe Henon ol' UNICEF Belgium ("or htx assistance.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed lo Katherine L. Hatfield, Department of Communication Studies, Creighton University, 2500 California Plaza, Omaha, Nebraska ()SI78. Email: katiehatfield®

creighton.edu

145

ARGUMENTATION AND ADVOCACY

HATFIELD ET AL.

perspective offers a focused lens with which to examine the Smurf PSA as a form of visual

argumentation. To understand better how the spot functions, we first will survey the

literature and outline Blair's theory of visual argument. Second, we will employ Blair's

perspective in order to investigate the UNICEF PSA as a visual argument. Finally, we will

offer several critical implications of this study.

VISUAL RHETORIC AND THE CASE FOR VISUAL ARGUMENTS

Rhetorical scholarship provides a space in which we are invited to investigate a n d grapple

with the communicative p h e n o m e n a that surround us. Ivie (1995) contends that rhetorical

scholarship has social relevance a n d produces knowledge about our lives. H e writes that

criticism

•».

reveals and evaluates the symbols that organize our lives within particular situations and that constitute the

civic substance motivating political action. It is a form of advocacy that is grounded in the language of a

particular rhetorical situation, its critique guided by the language of and about rhetorical theory, (p. 138)

Although Ivie is correct, we believe that scholars need to continue to explore the intersections of theory and rhetorical phenomena, especially those intersections that are visual in

nature.

In the latter half of the 1990s, scholars began a major effort to examine the role of the

visual in argumentation (Birdsell & Goarke, 1996; Blair, 1996; Cameron, 1996; Fleming,

1996; LaWare, 1998). LaWare (1998) suggests that this effort can be attributed to the "visual

orientation of contemporary society and the richness and complexity of visual images" (p.

140). Birdsell and Goarke (1996) argue that, because they are trained to focus on verbal

forms, "students of argumentation emerge without the tools needed for proficiency in

assessing visual modes of reasoning and persuasion" {p. 1). Foss (2004) notes: "Throughout

rhetoric's long tradition, discursive constructs and theories have enjoyed ideological hegemony, delimiting the territory of study to linguistic artifacts, suggesting that visual symbols

are insignificant or inferior, and largely ignoring the impacts of the visual in our world"

(p. 303). Visual symbols are pervasive, and our ignorance of them inhibits understanding of

much of the world around us.

Some may argue against including the visual in argumentation theory (Fleming, 1996),

generally based on two claims: (1) visual images are inherently ambiguous; and (2) arg^uments must be propositional (Blair, 1996, 2004; Foss, 2004). Blair (1996), however, suggests

that visual arguments fit nicely within traditional rhetorical paradigms and responds to both

of these claims.

First, Blair (1996) endorses O'Keefe's (1982) approach, in which an argument need not

actually be expressed in language but potentially couldhe expressed in language. Blair notes

that an argument must possess a claim and reason(s) for the claim, the claim and reasons

should be "linguistically explicable and overtly expressed," and there should be "an attempt

to communicate the claim and reason(s)" (p. 24). We agree that these characteristics

constitute an argument.

Second, O'Keefe (1982) asserts, and Blair (1996) agrees, that an argument must be

propositional. Arguments are propositional because they contain claims and reasons that can

be affirmed or rejected. Blair, however, adds that this can include visual arguments, which

he defines as "propositional arguments in which the propositions and their argumentative

function and roles are expressed visually" (p. 26). As an example, he suggests that the

146

j

UNICEF SMURF PSA

WINTER & SPRING 2007

groundbreaking 1996 Benetton advertising campaign. The United Colors of Benetton, is identifiable as a purely visual argument about race. Although acknowledging that this campaign

easily might have increased sales of Benetton clothing, he argues that its primary purpose,

and the purpose of most visual arguments, was not necessarily to sell a product. Rather, most

visual arguments raise consciousness about an issue.

On the other hand, not every image presents an argument. Blair (1996) explains that

context is essential to understanding the propositional quality of arguments, including visual

ones. For example, in a proposition such as "George is no longer on the tennis team," the

argument is not obvious. Only when we know the circumstances, such as that he really

enjoyed being on the team, can we infer that George left, but not out of choice. Then we have

a proposition, in "George is no longer on the tennis team," and a conclusion, such as

"Something unusual has happened." Without context, we have only potential arguments.

Visual images either create or use context to contain or imply propositional content.

Television commercials present unique theoretical challenges (Blair, 1996). Although

some commercials may argue, most merely evoke "underlying and hidden identifications

and feelings" (p. 34), whether rational or not, to motivate an audience to buy a product (in

commercial advertisements) or change a behavior (in public service campaigns). Because

television commercials often contain music, they are more likely to conjure an emotional

response from viewers. In fact, Blair contends, the effectiveness of commercials stems

primarily from their manipulation of feelings and identifications, not from their argumentation. The difference between persuasive manipulation and argumentation is conscious

choice. Unconscious appeals to emotions do not present audiences with an opportunity to

choose on the basis of rational analysis. Instead, audience members reach for one product

over another without really understanding why. Blair (1996) explains that the "reasons" put

forth in such commercials do not withstand critical analysis.

Blair's perspective expands the grounds of investigation into the realm ofthe visual. Given

advancements in technology that have made our society a media driven culture, study of

visual arguments is especially timely and important. Having explained Blair's approach, we

now tum our attention to the UNICEF PSA.

TESTING BLAIR'S APPROACH: THE

UNICEF

SMURF

PSA

The UNICEF PSA is unlike a typical television commercial that attempts to sell a product

or service. Employing images, music, and a brief verbal statement, it evokes feelings through

audiences' recollection of a familiar childhood melody (the Smurf tune). Yet, it also articulates an argument visually. To demonstrate this, we will show that the argument can be

expressed linguistically and discuss the context that completes the argument and accounts for

its effect on viewing audiences.

The PSA begins with upbeat music, birds chirping, and sun shining. Those familiar

with the children's cartoon will recall the excessively happy mood of the village in which

Smurfs hold hands as they dance and sing together. Soon, this happy music is replaced

by the sounds of explosions. Airplanes drop bombs on the Smurfs' mushroom houses,

wreaking havoc and engulfing the Smurf paradise in chaos. As the bombing subsides,

viewers survey the damage. Many Smurfs are lying on the ground, dead. Baby Smurf

cries among the carnage. In the final scene, text (in French) appears: "Don't let war

destroy the children's world" (see Figure 1). The apparent claim is that children in

147

ARGUMENTATION AND ADVOCACY

HATFIELD ET AL.

Figure 1; Still frame of UNICEF Belgium's "The Smurfs." Used by permission of IMPS.

war-torn countries need help, which we can provide through UNICEF. The Smurf

animation provides the reasons for this claim.

These reasons are threefold, and can be expressed linguistically. First, war leaves children

without a support network. The PSA shows Baby Smurf alone, without family or friends.

Baby Smurfs mother, Smurfette, and others who could act as parental figures, have been

killed. Baby Smurf is left crying among the corpses and ravaged village. The second reason

is that war is real and undeserved. The chirping birds and sing-song music at the beginning

of the PSA establish the happy and peaceful atmosphere of the Smurf world. This helps to

demonstrate the innocence of those victimized by war. Finally, the devastation of war

demands a commensurate response. The Smurf village is destroyed; only helpless Baby

Smurf survives, needing total aid. In this way, the PSA's claim and reasons can be expressed

linguistically.

In addition, use of the Smurfs provides an immediately understandable context for the

PSA's argument. The PSA avoids ambiguity by fusing today's conflicts with a well-known

children's cartoon series. Belgians identify strongly with the Smurf cartoon:

The Snitirfs-image was selected because apparently "the Snmrf cartoon" is the image most Belgians in the

30-45 years age group link with an image of a happy childhood. If we wanted to symbolically show the

impact of war and violence on childhood, this seemed to be the best image to use. (P. Henon, personal

communication, January (>, 2006)

:

This purposeful choice created a very specific context for understanding the plight of

children during war. At the same time, the PSA occurs in the context of UNICEF's

longstanding, ongoing efforts to generate support for their children's programs. Because

148

UNICEF SMURF PSA

WINTER & SPRING 2007

audiences understand UNICEF's purpose-raising fimds for child victims-the PSA is not

merely a potential argument but presents a definite claim and reasons.

| ,

Finally, the Smurf PSA does not rely on simplistic feelings to motivate its audience.

Although it does appeal to unconscious identifications, these are consistent with its conscious, rational appeals. This consistency is key to its success as a visual argument. The PSA

connects with audiences' memories of happy, innocent childhood. This is both an emotional

appeal and a conscious, rational idea. The audience first connects with the PSA subconsciously: Its images of gentle, peace-loving, and innocent Smurfs trigger pleasant memories

of childhood experiences watching cartoons. These images replicate those that once were

part of the audience's television viewing experience. This replication can evoke an emotional

response: When the PSA depicts the death of the Smurfs, viewers experience the death of

their childhood. In this way, they are shaken out of their complacencies to feel compassion

for the children.

Recall that the PSA's creators beheved that traditional appeals had lost their immediate

effect: Viewers had been desensitized to real images of war's devastation. The creators

sought to convey this devastation in a way that audiences both would comprehend and

respond to emotionally. The rational appeals are expressed in the emotional content of

innocent cartoon characters. Viewers reconstruct their ideals of childhood through the

Smurfs and transfer their concern for these imaginary cartoon characters to children, real

victims of conflict, now made real through visual portrayals of the Smurfs' suffering. The

consistency of emotional and rational appeals can be seen in the continued engagement of

those viewers who visit UNICEF's Belgian website and donate to the cause. We believe that

these viewers are not buying a product impulsively and unknowingly, but are fully engaging

an issue, thinking rationally about its merits as well.

IMPUCATIONS

'

Now that the Smurf PSA can be understood as an argument, we can consider four

implications. The first concerns the evocation of emotion in argument. Blair's perspective was moderately successful in distinguishing between advertisements that evoke and

advertisements that argue. He discusses the emotional impact of visual arguments in

terms of their ability to advance claims that can be determined to be either true or false.

However, this case study demonstrates the persuasive power of emotions generated by

visual arguments. The Smurf PSA exhibits the characteristics of an argument but also

evokes an emotional response. The power of its emotional appeal enables the message

to overcome audience exhaustion, persuading viewers to act. Previous messages failed to

elicit the desired response not because of a lack of truth-value but because audiences

needed an emotional push to act. The Smurf PSA overcomes compassion fatigue and

desensitization by distancing the audience from the emotional intensity of war and by

tying the message to a more personal emotional response.

The second implication concerns this visual argument's success in raising consciousness. The PSA was successful in three important ways. Traffic on the UNICEF website,

and specifically its link to the PSA, increased, suggesting that viewers at least were moved

to become more informed (Van Munching, 200.5). In addition, UNICEF Belgium raised

over 750,000 euros (P. Henon, personal communication, February 14, 2006). This Is a

significant amount: At the same point in 2006 when the Smurf campaign had raised half

ARGUMENTATION AND ADVOCACY

HATFIELD ET AL.

a million euros, UNICEF Belgium's fundraising effort for victims of Pakistan's recent

earthquake had netted but 65,000 euros (P. Henon, personal communication, January 6,

2006). Finally, this campaign succeeded in stimulating "talk": "People and media 'talked'

about it, people have logged into our website and school teachers talked about our

campaign in their classrooms. 80% of reactions we received from other parts ofthe world

were also positive and supporting" (P. Henon, personal communication, January 6,

2006). The association of publicity agencies in Belgium conferred its Merit Award for the

best campaign commercial on the PSA, and the campaign received high praise from

numerous other UNICEF organizations.

The third implication concerns aesthetic form. The Smurf PSA departs from UNICEF's

typical campaigns. UNICEF has spent years developing an aesthetic style that adamantly

eschews actual footage of war but depicts a spokesperson surrounded by orphans of war.

Thus, audiences generally see the real aftermath of war but are spared the trauma of war

itself. The Smurf PSA departs from this formula by depicting war itself, but also does so via

the added aesthetic distance afforded by animation. Fictional, lovable, and familiar cartoon

characters temper the shock and awe of war.

Aesthetically, the PSA engages desensitized publics by employing familiar images to

reposition an important social issue in a context that viewers easily and readily understand.

Those in charge of persuasive campaigns for a variety of social causes should take note. From

AIDS to addiction, hurricane relief to homelessness, the use of personally familiar images to

create a new context for understanding claims on compassion might be a useful strategy to

address the problem of desensitized publics.

Finally, and relatedly, the PSA's departure from UNICEF's traditional formula alters our

understanding of acceptable violence. Although UNICEF consistently has declined to show

footage of real war, it has determined that cartoon bombings are acceptable. Of course,

cartoon mayhem is a Saturday morning staple, but the Smurf PSA is not entirely makebelieve. This may raise some concern among those who study the impact of cartoon

violence. Even UNICEF's decision to air this PSA only in the evenings acknowledges this

concern. Moreover, children may be traumatized not simply by the violence per se but by

the death of favorite cartoon characters. This invites the question: Is the distinction between

real and animated violence tenable? In our opinion, the answer is "no." The power of the

visual should not be taken lightly. Visual images have the power to move an audience into

action; responsible rhetors must consider the unintended consequences of their argumentative choices.

FUNCTIONAL ELEMENTS OF VISUAL ARGUMENTS

UNICEF Belgium's goal was to overcome compassion fatigue in order to increase

contributions to child relief efforts. Several characteristics of the Smurf PSA appear to have

contributed to this goal's attainment, enabling us to consider not simply whether visual images

can argue but how they can do so.

These characteristics, which may be universal in visual arguments, include medium,

realism, detail, abstraction, and ambiguity. Medium concerns the channel(s) through which

the message is transmitted, including sound, movement, color, and light. Visual arguments

often layer several media that contribute to the construction of a message. Realism concerns

the degree to which the image accurately reflects the object that it is intended to represent

in the argument. Realism concerns the image per se, not whether an audience perceives an

]50

UNICEF SMURF PSA

WINTER & SPRING 2007

image to be "real" or ''imaginary." Other characteristics, such as medium, detail, and

abstraction, may be used to increase or decrease an image's realism but are not intrinsically

linked to realism. Detail involves those minute elements that contribute to the visual

argument. It does not refer simply to the quantity of information in or realism of an image

but, rather, to details in the argument. The level of detail may vary within a visual argument.

Abstraction is the degree to which the image transcends any particular instance. Highly

abstract images may be generalized more easily to a wider range of contexts than less

abstract images. A highly detailed image with a low level of abstraction may not be clearly

connected with a particular person, time, or location. Finally, ambiguity is the degree to which

multiple meanings may attach to an image. The more senses in which an image can be

understood, the higher its level of ambiguity.

Each of these characteristics is present in the Smurf PSA. First, the PSA layers multiple

media in order to reach its audience. Its beginning employs sound to create the sense of a

happy life and childhood. Deployment of the cartoon's theme song immediately brings

images ofthe television program to mind for viewers. The PSA also varies lighting to build

its argument. Its beginning is brightly lit, reinforcing the happy mood, while, after the

bombing of the Smurf village, images tum dark. These media reinforce one another and the

PSA's argument: Sound connects the audience to childhood experiences while lighting

reinforces emotional responses to events depicted in the cartoon.

Second, varying levels of abstraction are evident. At first, animated characters represent

the human casualties of war, reducing the image's realism. However, this abstract depiction

of human suffering may be effective in reaching viewers who have become desensitized to

more realistic images of suffering. Also, the images of Smurfs are highly realistic in a different

sense, namely, as representations of familiar images from viewers' childhoods. The animation prompts a recollection that evokes an emotional response and makes the argument

personal.

The PSA also shifts levels of detail in order to emphasize particular aspects ofthe image.

At the beginning, images of animals and the forest are very detailed. These details of nature

contribute to the argument by elaborating an environment filled with furry happiness. Later,

less detailed images encourage viewers to contemplate war in general, not specific damages

or deaths.

The PSA manipulates abstraction not only in order to deflect the concrete horrors of war

but also to make its message relevant to any military conflict in which children are

victimized. The first helps to break through barriers like compassion fatigue while the second

increases the PSA's utility.

Finally, the PSA manipulates ambiguity. In the cartoon. Baby Smurf, the only child, is a

minor, little developed character; s/he does not talk and plays a small role. Thus, as a

character. Baby Smurf is ambiguous. But, because s/he is ambiguous, s/he also can represent

all children. In its final scene, s/he is shown crying amidst the destroyed Smurf village. Baby

SmurFs ambiguity as a character contributes to a visual argument whose claim is unambiguous.

I

CONCLUSION

I

i

This paper sought to investigate both the possibility and nature of visual argument through

examination of a particular case: UNICEF Belgium's Smurf public service announcement.

J. Anthony Blair's work enabled us to analyze this PSA's significance as a visual argument.

151

ARGUMENTATION AND ADVOCACY

HATFIELD ET AL.

Finally, we extended his work by offering several implications concerning the form and

functional elements of visual argtiments. It is our hope that this essay will prompt further

conversation about visual argumentation and the ethical challenges that arguers face when

crafting messages, both verbal and visual.

The Smurf PSA raises several avenues for future research. For example, because they

often are part of larger persuasive campaigns conducted over an extended period of time, it

often is difficult to isolate the effects of individual visual arguments. Additionally, the

methods by which visual arguments can be translated propositionally and context can be

specified require development.

We strongly encourage scholars to engage further in this area of inquiry. As we become

increasingly aware of the power of visual arguments, we must test our theoretical commitments. We must step outside of the comfort zone of our traditional modes of thinking to see

what we can leam from alternate sites of interest.

REFERENCES

Blair, J. A. 1996). The possibility and actuality of visual argument. Argumentation and Advocacy, 33, 2;i-39.

Blair, J. A. 2004). The rhetoric of visual arguments. In C. A. Hill & M. Helmers (Eds.), Defining visual rhetorics {pp.

41-62). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Birdsell, D. S., & Goarke, L (1996). Toward a theory of visual argument. Argumentation and Advocacy, 33, 1-10.

Cameron, S. (199(j). Rhetorical and demonstradve modes of visual argument: Lookingat images of human evolution.

Argumentation and Advocacy, 33, 5 3 - 6 9 .

FAQ: "Smurfs: What's it all about?" ('i()()5). Retrieved June 26, 2007, from http://www.unicef.org/media/

media_28772.htm!

Heming, D. (1996). Can pictures be arguments? Argumentation and Advocacy, 33, 11-22.

Foss, S. K. (2004). Framing the study of vistial rhetoric: Toward a iraaisformation of rhetorical theory. In C. A. Hill

& M. Helmers (Eds.}, Defining visual rhetorics (pp. 303-314). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Ivie, R. L. (199,'j). The social relevance of rhetorical scholarship. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 81, 138.

i-aWare, M. R. (1998). Encountering visions of Aztlan: Arguments for ethnic pride, community activism and cultural

revitalization in Chicano murals. Argumentation and Advocacy, 34, 140-154,

O'Keefe, D. J. (1982). The concepts of argument and arguing. In J. R. Cox & C. A. Willard (Eds.), Advances in

argumentation theory and research (pp. 3-23). Carbondale: Southem Illinois University Press.

Rennie, D. (2005, October 8). UNICEF bombs the Smurfs in fund-raising campaign for ex child soldiers. ITie Daily

Telegraph. Retrieved November 10, iiOO.5, from www.telegraph.co.uk/news/main.jhtmt?xml=/news/2t)0.'j/10/08/

wsmurfi)8.xml&sSheel=/news/2()05/10/08/ixhome.html

Spongenberg. H. (2005, October 11). Smurfs bombed in UNICEF ad to highlightplight of ex-child soldiers in Africa.

eNewMexican. Retrieved November 10, 2005, from hltp://www.freenewmexican.com/news/33541.html

Van Munching, I'. (2005, October 17). The Devil's adman: UNICEF's Smurfageddon. Brandweek. Retrieved June 26,

2007, from I^xis-Nexis Academic Universe database.